Medicaid Managed Care Rates and Flexibilities: State Options to Respond to COVID-19 Pandemic

Key Takeaways

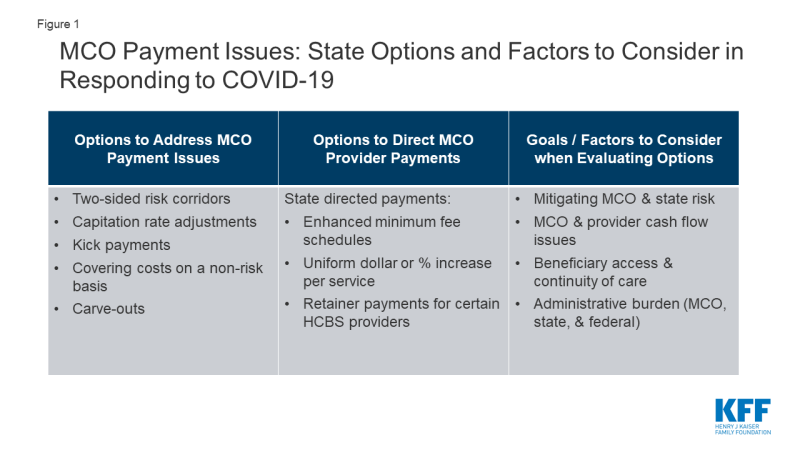

With 69% of Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in comprehensive managed care plans, plans play a critical role in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic and in the fiscal implications for states. Given unanticipated costs related to COVID-19 testing and treatment, as well as depressed utilization affecting the financial stability of many Medicaid providers, states are currently evaluating options to adjust current managed care organization (MCO) payment rates and/or risk sharing mechanisms as well as evaluating options and flexibilities under existing managed care rules to direct payments to Medicaid providers (Figure 1). This brief provides an overview of how MCO capitation rates are developed by states and approved by CMS, highlights options available to states to adjust current MCO payment rates and/or risk sharing mechanisms, describes how MCOs pay providers, and outlines state options to direct MCO payments to providers in response to conditions created by the pandemic. Key takeaways are discussed below.

Under federal law, payments to Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) must be actuarially sound. Actuarial soundness means that “the capitation rates are projected to provide for all reasonable, appropriate, and attainable costs that are required under the terms of the contract and for the operation of the managed care plan for the time period and the population covered under the terms of the contract.” Unlike fee-for-service (FFS), capitation provides upfront fixed payments to plans for expected utilization of covered services, administrative costs, and profit.

Under existing Medicaid managed care authority, states have several options to address payment issues that have arisen as a direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic. CMS has outlined state options to modify managed care contracts and rates in response to COVID-19 including risk mitigation strategies, adjusting capitation rates, covering COVID-19 costs on a non-risk basis, and carving out costs related to COVID-19 from MCO contracts. These options vary widely in terms of implementation/operational complexity, and all options will require CMS approval.

States can direct that managed care plans make payments to their network providers using methodologies approved by CMS to further state goals and priorities, including COVID-19 response. This strategy can address the scenario in which states are making capitation payments to plans, but providers are not receiving reimbursement from plans due to decreased service utilization while non-urgent services are suspended or patients are hesitant to seek care. For example, states could require plans to adopt a uniform temporary increase in per-service provider payment amounts for services covered under the managed care contract, or states could combine different state directed payments to temporarily increase provider payments.

Key considerations in evaluating payment options include: mitigating MCO and state risk, MCO and provider cash flow, beneficiary access and continuity of care, and administrative burden. States may consider how payment policy options impact both MCO and state financial risk, as capitation rates do not include costs associated with COVID-19 but the pandemic has also led to decreased utilization of services. States may also consider MCO cash flow issues that may arise due to unanticipated costs associated with COVID-19 as well as provider cash flow issues as a result of depressed utilization. It will also be important to consider the impact of payment options on beneficiary access and continuity of care (i.e., will beneficiaries be able to maintain relationships with existing providers). Finally, all options require CMS review and approval but options may vary widely in terms of implementation/operational complexity.

Introduction

Today, capitated managed care is the dominant way in which states deliver services to Medicaid enrollees. States pay Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) a set per member per month payment for the Medicaid services specified in their contracts. Current MCO capitation rates were developed and implemented prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, these rates do not include costs for COVID-19 testing and treatment. At the same time, utilization of non-urgent care is decreasing as individuals seek to limit risks/exposure to contracting the coronavirus. As a result, many states are currently evaluating options for making adjustments to existing MCO rates and risk sharing mechanisms in response to unanticipated COVID-19 costs and conditions that have led to decreased utilization. However, there is still a lot of uncertainty about the impact of the pandemic on managed care financing/rates, particularly in current plan rating periods (which typically run on a calendar year or state fiscal year basis), as it’s still too early to know if there is pent up demand that may drive utilization upward as the pandemic abates as well as unknowns about where/when COVID-19 cases and related costs will spike as the pandemic continues.

Additionally, many Medicaid providers may be under fiscal strain, facing substantial losses in revenue.1 For providers in states that rely heavily on managed care, states are making payments to plans but those funds may not be flowing to providers where utilization has decreased. In contrast, many health insurance companies are reporting record earnings during the pandemic.2 As a result, states are also evaluating options and flexibilities under existing managed care rules to direct/bolster payments to Medicaid providers.

This brief provides an overview of how MCO capitation rates are developed by states and approved by CMS, highlights options available to states to adjust current MCO payment rates and/or risk sharing mechanisms, describes how MCOs pay providers, and outlines state options to direct MCO payments to providers in response to conditions created by the pandemic.

Background

As of July 2019, 40 states, including DC, contract with comprehensive, risk-based managed care plans to provide care to at least some of their Medicaid beneficiaries. Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) provide comprehensive acute care (i.e., most physician and hospital services) and in some cases long-term services and supports to Medicaid beneficiaries. MCOs accept a set per member per month payment for these services and are at financial risk for the Medicaid services specified in their contracts.

As of July 2018, almost 54 million Medicaid enrollees received their care through risk-based MCOs – or over two thirds (69%) of all Medicaid beneficiaries. Twenty-five MCO states covered more than 75% of Medicaid beneficiaries in MCOs. In FY 2018, state and federal spending on Medicaid services totaled nearly $593 billion. Payments made to MCOs accounted for about 45% of total Medicaid spending. State-to-state variation in MCO spending reflects many factors, including the proportion of the state Medicaid population enrolled in MCOs, the health profile of the Medicaid population, whether high-risk/high cost beneficiaries (e.g., persons with disabilities, dual eligible beneficiaries) are included in or excluded from MCO enrollment, and whether or not long-term services and supports are included in MCO contracts. Six firms – UnitedHealth Group, Centene, Anthem, Molina, Aetna, and Wellcare – accounted for over 47% of all Medicaid MCO enrollment in July 2018.

How do states set payment rates for MCOs?

Under federal law, payments to Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) must be actuarially sound.3 Actuarial soundness means that “the capitation rates are projected to provide for all reasonable, appropriate, and attainable costs that are required under the terms of the contract and for the operation of the managed care plan for the time period and the population covered under the terms of the contract.” The 2016 final rule on Medicaid managed care significantly strengthened the standards that states must meet in developing actuarially sound capitation rates and that CMS will apply in its review and approval of rates. Payments made to Medicaid managed care plans vary depending on the scope of services and populations covered by the plan. Unlike fee-for-service, capitation provides upfront fixed payments to plans for expected utilization of covered services, administrative costs, and profit.

In developing actuarially sound rates, states must follow accepted actuarial methods and specific federal requirements outlined in regulations and other guidance. Plan rates, usually for a 12-month rating period, are set using baseline utilization and cost data based on historical FFS claims, health plan services and utilization data (i.e., encounter data), and/or health plan financial data for the populations enrolled. Baseline spending data is trended forward to determine per member per month payment amounts and must take into account/adjust for factors such as medical cost inflation, expected changes in utilization, and state Medicaid program changes (e.g., changes to eligibility, benefits, cost-sharing, FFS payment rate changes (if state bases managed care rates on FFS rates)). Different rates are set for population subgroups (referred to as “rate cells”) taking into account eligibility category, age, gender, location, among other factors. Rates also include expected non-benefit costs including administration, taxes, licensing and regulatory fees, contribution to reserves, risk margin, and cost of capital.4,5,6

States may use a variety of other mechanisms to adjust plan risk (including catastrophic claims), incentivize plan performance, and ensure payments are not too high or too low, including:

- Risk & Acuity Adjustments – Rates can be risk adjusted to account for the health status (or other demographic factors) of enrollees which may reduce the incentive for plans to avoid sicker members. Acuity adjustments are applied to total payments across all managed care plans to account for significant uncertainty about the health status or risk of a population.

- Risk Sharing Arrangements– Rates may take into consideration the use of plan risk sharing mechanisms including risk corridors, stop-loss, or reinsurance. Under risk corridor arrangements, states and plans agree to share profit or losses (at percentages specified in plan contracts) if aggregate spending falls above or below specified thresholds (two-sided risk corridor). Stop-loss and reinsurance arrangements protect plans from losses beyond a specified threshold.

- Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) – The MLR reflects the proportion of total capitation payments received by an MCO spent on clinical services and quality improvement (where the remainder goes to administrative costs and profit). CMS published a final rule in 2016 that requires states to develop capitation rates for Medicaid to achieve an MLR of at least 85% in the rate year. Contracts must include a requirement for plans to calculate and report an MLR. There is no federal requirement for Medicaid plans to pay remittances to the state if they fail to meet the MLR standard but states have discretion to require remittances – 24 states reported that they “always” require MCOs to pay remittances while six states indicated they “sometimes” require MCOs to pay remittances, as of July 1, 2019.7

- Incentive & Withhold Arrangements – States may factor payment mechanisms like incentive and withhold arrangements into rate development. Using incentive arrangements, states may make payments over and above capitation rates to plans for meeting specified performance targets. Under withhold arrangements, states may hold back a portion of capitation rates to be paid if/when plans meet specified performance targets (e.g., quality performance measures or quality-based outcomes).

After CMS approval, states may increase or decrease rates by 1.5% (per rate cell) without requiring new approval. CMS must review and approve capitation rates including supporting data and documentation for a 12-month rating period. States must update capitation rates and seek approval from CMS each year before new rates become effective. States must obtain federal approval for adjustments that exceed 1.5%.

What guidance has CMS provided to states to address MCO payment issues in response to COVID-19?

Under existing Medicaid managed care authority, states have several options to address payment issues that have arisen as a direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic. CMS has acknowledged that costs associated with the COVID-19 pandemic could not have been reasonably prospectively included in the development of current MCO rates. CMS has also noted that the COVID-19 public health emergency is causing major shifts in utilization across the healthcare industry, causing uncertainty for health care providers. In response, CMS has outlined state options to modify current managed care contracts and rates in response to COVID-19.8 CMS discussed several options available to states and outlined key considerations in evaluating these options including: mitigating MCO and state risk, MCO cash flow, beneficiary continuity of care, and administrative burden (for states, the federal government, and MCOs). The following options described below will all require CMS approval. States will need to submit MCO contract amendments and in most instances revised actuarial certifications. (Also see box below for specific examples discussed on CMS stakeholder call related to options for covering COVID-19 tests.)

States can implement two-sided risk corridors. Most states have experience with risk corridors. Risk corridors can mitigate MCO risk without impacting enrollee continuity of care, as beneficiaries would be able to continue to see existing providers in their plan network. CMS advises states should implement risk corridors for all medical costs, not just COVID costs, noting it is simpler to implement for all medical costs and doing so accounts for risks related to non-COVID costs changes. Risk corridors provide financial protection to MCOs and limits on financial risk to states but would not address immediate MCO cash flow issues, as they would be reconciled and paid out at the end of the contract period. In its May 2020 guidance, CMS notes states could implement two-sided risk corridor based on a target MLR – where a plan and the state would be required to share in gains or losses if the plan did not meet the target MLR within a specified margin. CMS will consider state requests to retroactively amend or implement (for current rating periods) risk mitigation strategies (e.g., risk corridors) only for the purpose of responding to the COVID-19 pandemic.9,10

States can adjust capitation rates. Risk corridors can be combined with a capitation rate adjustment to address MCO cash flow risks. Many states are implementing temporary increases in Medicaid FFS provider payment rates as part of disaster State Plan Amendments (SPAs). Some states have CMS approved state directed payments which contractually require managed care plans to adopt Medicaid FFS provider rates for specific provider types or services. States can make rate adjustments in response to COVID-19 that result in an increase or decrease to the capitation rate per rate cell of less than 1.5% with a contract amendment (but do not need a revised actuarial certification). For adjustments of more than 1.5% per rate cell, states must submit a revised actuarial rate certification and contract amendment to CMS. States can submit prospective or retrospective rate amendments (for the current rating period) associated with COVID-19 (or adjust for non-COVID-19 costs) but CMS has noted that a significant amount of uncertainty still exists around the spread of the pandemic and costs associated with treatment, which would make it very difficult to develop assumptions or assess the reasonableness of final rates/rate adjustments.

States can incorporate supplemental kick payments. Kick payments are one-time fixed, supplemental payments made to plans, allowing them to cover certain services (e.g., maternity care) without assuming financial risk for their use. States could use kick payments to cover COVID-related costs, which would require a contract amendment and rate certification.

States can cover COVID-19 costs on a non-risk basis. This could include all COVID-19 related service costs or all service costs for beneficiaries with a COVID-19 diagnosis. States would then reimburse MCOs for these costs net of capitation payments paid. CMS noted that this option could also be combined with a risk corridor to reduce the risk that remaining costs are significantly lower than originally projected. Covering costs on a non-risk basis would eliminate MCO risk, reduce MCO cash flow problems, and ensure continuity of care for beneficiaries. However, the success of the non-risk model would depend on accurately identifying relevant costs/enrollees.

States can carve-out costs related to COVID-19 and cover them on a FFS basis. States could either carve out all COVID-19 related service costs or all service costs for beneficiaries with a COVID-19 diagnosis. Again, CMS would recommend implementing with a risk corridor. A COVID-19 carve-out would be administratively burdensome and would disrupt beneficiary continuity of care, especially in states that heavily use managed care that don’t have much of a FFS provider network to utilize. This model would also depend on accurately identifying all COVID-19 costs and/or beneficiaries.

CMS Guidance: Options for Covering COVID-19 Tests11

If health plans are responsible for providing laboratory services, they must cover the COVID-19 test. However, if approved capitation rates are not sufficient to cover the costs of the tests, states may consider:

- Making actuarially sound rate adjustments – states could amend rates to include cost adjustment.

- Creating kick payment for plans to cover test.

- Paying for tests outside capitation as non-risk payment, either through separate non-risk contract with plans or amendment to existing contact. (State needs to comply with upper payment limits (UPLs) for non-risk contracts.)

States may also consider adjusting their managed care contract quality measurement requirements. States may need to revisit contract provisions that have been affected by pandemic in ways that were not anticipated. CMS has indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to affect clinical practices and timely reporting of quality data. States may need to reexamine arrangements tied to performance metrics/reporting requirements such as withhold and incentive arrangements, state-directed payments, as well as other contract requirements and penalties. Depending on the nature of the changes, rate certification amendments may or may not be needed; however, states will need to submit contract amendments to reflect any revisions to these provisions.

How do MCOs pay providers?

States generally pay the plans a capitation payment, but then plans determine how to pay the providers in their network.12 Plans generally have wide latitude to determine how to pay their contracted providers. Medicaid MCOs may pay the providers in their networks on a FFS basis, capitation basis, or on other terms. Although plans may use alternative provider payment models (e.g., capitation, bundled payments etc.) for some providers, MCOs still widely use FFS reimbursements to pay providers.

Under current MCO rules, states are prohibited from directing how a managed care plan pays its providers except for certain payment methodologies that have been approved and reviewed by CMS. States may require MCOs to adopt minimum or maximum provider payment fee schedules or provide uniform dollar or percentage increases for network providers that provide a particular service under the contract, as approved by CMS. States also can seek CMS approval to require MCOs to implement value-based purchasing models for provider reimbursement (e.g., pay for performance, bundled payments) or participate in multi-payer or Medicaid-specific delivery system reform or performance improvement initiatives. State directed payments must be based on utilization and delivery of services covered under the managed care plan contract and must be reflected in capitation rate development and certification.13

What guidance has CMS issued related to state options to direct MCO provider payments in response to conditions created by the COVID-19 pandemic?

States can direct that managed care plans make payments to their network providers using methodologies approved by CMS to further state goals and priorities, including COVID-19 response. This strategy can address the scenario in which states are making capitation payments to plans, but providers are not receiving reimbursement from plans due to decreased service utilization while social distancing measures are in place and non-urgent services are suspended. For example, states could require plans to adopt a uniform temporary increase in per-service provider payment amounts for services covered under the managed care contract, or states could combine different state directed payments to temporarily increase provider payments, according to recent CMS guidance. Specific examples from the CMS guidance are outlined in the box below. CMS will allow states to develop and implement these specific state directed payments retrospectively to the start of the current contract rating period.

State Directed Payment Examples from CMS Guidance14

- A state may direct and contractually require their managed care plans to pay an enhanced minimum fee schedule for pediatric primary care providers.

- A state may direct and contractually require their managed care plans to pay a uniform dollar or percentage increase per service rendered by behavioral health providers. The amount the state directs the plan to pay per service could vary quarter-to-quarter based on utilization – where the uniform dollar or percentage increase is determined by dividing total dollars the state has dedicated to this payment arrangement (per quarter) by the number of behavioral health visits in a given quarter.

CMS explains that state directed increased payments for actual utilization of services can preserve the availability of covered services for enrollees during a time when providers may be experiencing dramatic utilization declines or incurring additional costs due to the public health emergency. The guidance also says that states may use directed payments to address increased use of telehealth or other approaches to maintain access to care for all enrollees or specific subgroups with specialized needs during the emergency. States must direct payments to a class of providers, such as dental, behavioral health, home health and personal care, pediatric, federally-qualified health centers, or safety-net hospitals, to support providers that may serve a high proportion of Medicaid enrollees and may be disproportionately affected by the public health emergency. Directed payments must be appropriate and reasonable compared to the total payments the provider would have received in the absence of the public health emergency.15 For states that have approved directed payment proposals, CMS guidance says that states wishing to make changes to such arrangements in light of COVID-19 can submit an amended directed payment preprint and/or contract and rate certification amendments to CMS.

To the extent that home and community-based services (HCBS) are included in MCO contracts, states may contractually require MCOs to make retainer payments to allow certain HCBS providers to continue to bill for individuals enrolled in Medicaid even if HCBS services (e.g., habilitation and personal care) cannot be provided during a public health emergency. The retainer payments must be authorized as part of the Section 1915(c) HCBS waiver, Section 1115 demonstration waiver, or other Medicaid authority. To effectuate these payments, states must submit a directed payment preprint to CMS for approval.

Looking Ahead: What to Watch

With 69% of beneficiaries enrolled in comprehensive Medicaid managed care plans, plans play a critical role in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Given unanticipated costs related to COVID-19 testing and treatment as well as depressed utilization affecting the financial stability of many Medicaid providers, states are currently evaluating options to adjust current MCO payment rates and/or risk sharing mechanisms as well as evaluating options and flexibilities under existing managed care rules to direct MCO payments to Medicaid providers. Key considerations in evaluating these options include:

- Does the policy mitigate risks to MCO and states? Some MCO payment options like rate adjustments, kick-payments, or covering costs on a non-risk basis may mitigate risks to MCOs. Other options like rate adjustments and the use of two-sided risk corridors may mitigate both risks to MCOs and states. However, states may need to consider where they are in their rate cycle, as money may not be returned to states, or additional funding provided to MCOs, until after the end of the rating period (when options like risk corridors or retrospective rate adjustments are used). Going into the next contract period, states will face continued challenges in setting rates as uncertainty about new costs and utilization will remain. Additionally, will CMS revisit some proposals in its Proposed Medicaid Managed Care Rule like the current provision which would prohibit states from retroactively adding or modifying risk sharing mechanisms after the start of the rating period?

- Does the option address MCO or provider cash flow issues? States may consider the fiscal stability/viability of both MCOs and providers and the timing of when additional funding might be paid out. Some policy options, like HCBS retainer payments, are limited to a 90-day cap per individual. States and providers may need to consider alternative options when this period ends.

- Does the policy enhance enrollee access or continuity of care for enrollees? States may consider the impact of payment policy options on beneficiary continuity of care, as some options – like carving out services to FFS systems – may disrupt established beneficiary-provider relationships. States considering directed payments could consider how policy options may enhance access to care for enrollees (including access to telehealth services).

- How feasible are the options given uncertainty about COVID-19 costs and the spread of the pandemic? And, how administratively burdensome are the options for states, the federal government, and plans? Both retroactive and prospective rate adjustments may be extraordinarily difficult to develop and implement because of significant uncertainty related to COVID-19 costs and utilization. States may consider what is required for approval – contract amendments, actuarial rate certification amendments, and/or state directed payment pre-prints and whether options under consideration may meet criteria for expedited review at CMS as well as the implementation/operationalization complexity and how quickly they may be able to get new monies out to plans and providers.

Looking to the future, the duration of the temporary increase in the federal Medicaid match rate as well as overall state fiscal conditions will also be factors states must consider when evaluating policy options in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Reduced state revenues and projected state budget shortfalls will likely put pressure on state Medicaid programs and states’ ability to pay for any policies that increase state costs, particularly without additional federal support or certainty about the duration of the current enhanced federal funding. States will want to carefully review options to mitigate risks related to overpayments to MCOs in a time of heightened uncertainty and state fiscal constraints. Due to significant challenges around revising rates for current contract periods (either retrospectively or prospectively), CMS is likely to encourage states to include two-sided risk corridors as part of state strategies to guard against overpayment.