Introduction

Since their 1965 beginning as a small War on Poverty experiment, community health centers have matured into a principal part of the health system for thousands of medically underserved urban and rural communities that experience elevated poverty and health risks. In 2017, 1,373 federally-funded health centers operating in over 11,000 community locations nationwide cared for 27.2 million patients. Health centers serve patients of all ages and provide an entry point into specialized care, and frequently, a bridge to services aimed at addressing underlying social determinants of health. To provide this care, health centers rely on multiple funding sources. The two major funding sources are Medicaid payments for covered services furnished to enrollees who are health center patients, along with federal grants made pursuant to Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act, which establishes and authorizes the health centers program. This issue brief describes health centers’ role in health care and these two primary sources of health center revenue—Medicaid and Section 330 funding. The evolution of these funding streams has contributed to significant growth in the health center program, enabling expanded services to millions of additional residents of the nation’s most medically underserved rural and urban communities.

Background

Health centers play an especially important role for certain patient populations. Health centers serve communities facing many challenges, including elevated poverty, increased health risks, and shortages of primary care and other providers. Reflecting the characteristics of these communities, in 2017, nearly all health center patients (91%) were low-income, and 69% were poor (Figure 1). Compared to other low-income populations, health center patients tend to be in poorer health. In 2017, nearly half (49%) of all health center patients were covered by Medicaid and over one in five (23%) were uninsured. To ensure access to affordable care, health centers adjust their charges in accordance with patient income. Charges cannot exceed the cost of care, and payment discounts must apply to both uninsured patients and those who are underinsured and face the cost of uncovered services (such as adult vision and dental care) and high cost sharing.

Health centers have increasingly adopted a comprehensive approach to patient care by providing a broad array of physical health, behavioral health, and supportive services. Health centers’ focus on addressing the needs of vulnerable, underserved communities is reflected in approaches to care not typical of standard medical practices, such as the integration of physical and mental health care services, location in community settings, such as schools and homeless shelters, and the provision of on-site services for addiction treatment and recovery and oral health. This co-location and integration of services enables health centers to participate in Medicaid delivery and payment reform strategies aimed at improving health care quality and efficiency and to serve as an entry point into a broader array of services.

What are the sources of health center revenue?

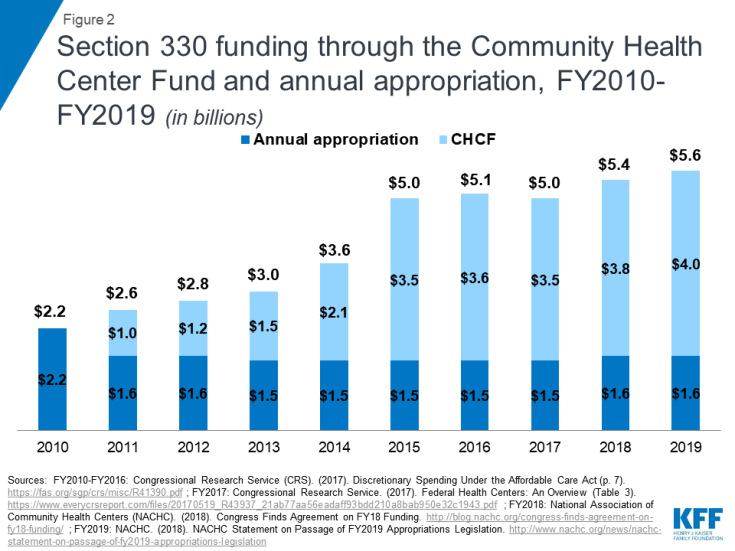

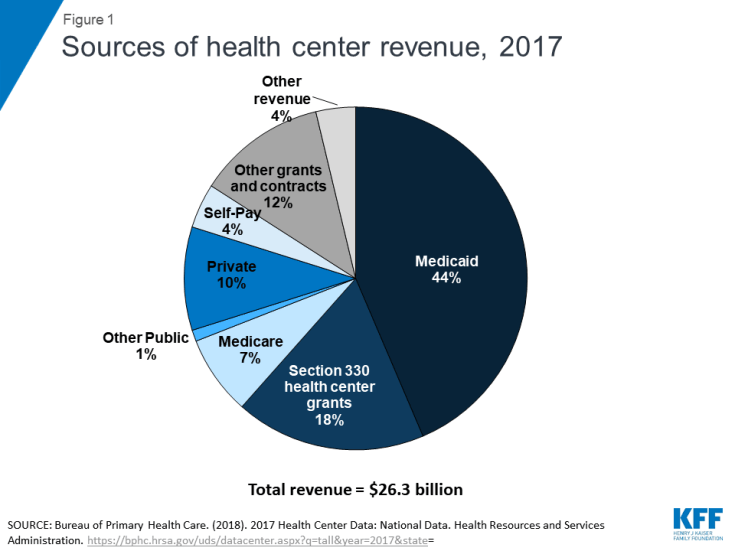

Revenue from Medicaid and Section 330 grant funding account for nearly two-thirds of health center funding. Like all health care providers, health centers derive their operating revenue from multiple sources. In the case of health centers, these sources are public and private insurance payments, grants from public and private funders, and patient out-of-pocket payments. Reflecting the federal law under which they operate as well as the poverty of their patients, health centers rely most heavily on Medicaid revenue and their ongoing operating grants under Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act, which authorizes the health centers program. Medicaid accounts for 44% of operating revenue nationally; Section 330 grants account for 18%; together, these two funding sources represent nearly two thirds of health center funding (Figure 1). Other revenue sources, while notable, play a less significant role. Private insurance accounts for 10% of health center revenue, while Medicare represents 7% of revenue. Direct patient payments account for only 4% of all revenue, a reflection of the poverty of health center patients.

Figure 1: Sources of health center revenue, 2017

Health centers also receive funding from other sources, to be used to provide specific services or to serve specific populations. Examples of these dedicated funding streams include grants for preventive reproductive health care under the Title X family planning program, Veterans Administration service contracts covering veterans who are patients, and contracts with state or local corrections authorities for services furnished inside a correctional institution or care for former inmates transitioning to the community. Health centers also receive state and local public health grants for preventive services such as funds to help support the cost of vision screening or services to screen and treat for communicable diseases. In total, these other federal, state, local, and private grants and contracts account for 12% of all health center operating revenue.

How do Medicaid’s special payment rules support health centers?

Medicaid pays health centers under the Prospective Payment System (PPS), which ties payments to the costs of delivering care. Health centers are a federally recognized type of Medicaid provider. Like all health care providers, to participate in their state Medicaid program, health centers must meet any reasonable conditions that states may apply to health care providers generally, such as basic licensure rules. However, unique to health centers and rural health clinics is a requirement that state Medicaid programs pay them according to a special cost-related payment formula. The purpose of these cost-related payment rules in Medicaid is to ensure that federal grant funds are used to pay for uninsured or under-insured patients and important but uncovered services and do not have to absorb uncovered costs associated with providing covered services to Medicaid patients. The earliest health center payment rules were added to Medicaid in 1990, while the current PPS was established in 2000 by the Medicare, Medicaid and SCHIP Benefits Improvement and Protection Act. PPS applies to both health centers and rural health clinics, and it is designed to ensure that, in keeping with early policy assumptions regarding Medicaid’s role in sustaining health centers as a principal source of primary care in underserved communities, Medicaid payments reasonably approximate the cost of care. The PPS payment system also applies to Medicare and CHIP, as well as payments made by Qualified Health Plans certified under the Affordable Care Act.

Under PPS, each health center receives a predetermined per visit rate based on the cost of services to Medicaid patients. This rate is updated annually to reflect medical inflation. PPS rates are also updated to reflect costs associated with the addition of new Medicaid-covered services such as on-site substance use disorder treatment and recovery services, expanded physical and speech therapy services for children with developmental disabilities, or dental services.

Under Medicaid PPS rules, state Medicaid agencies and their health centers may jointly develop alternative payment methodologies (APMs) to test innovative payment approaches. Such payment methodologies include all-inclusive payment rates for certain types of ongoing care or certain populations (e.g., a global annual payment for patients receiving health home services, or an all-inclusive per-member-per-month payment rate for all patients of the health center). States and health centers have begun to test such alternative payment models in order to experiment with approaches that better tie payment to performance rather than the volume of care furnished; models must maintain basic protections against steep revenue shortfalls of the type that led to the establishment of the PPS system in the first place.The Medicaid PPS model has ensured that payments to health centers remain somewhat related to the cost of care; however, while PPS maintains a degree of alignment between cost and revenue, costs continue to rise faster than the payment rate. In 2010, Medicaid paid 81% of health centers’ cost-linked charges; by 2017, payments only covered 79% (Table 1). But even with this gap, Medicaid is a far stronger payer than Medicare or private insurance. Although Medicare also uses the PPS formula, Medicare covers a more limited scope of primary care and mental health services and requires higher patient cost-sharing. For example, Medicare excludes vision and dental care, meaning that in serving low-income Medicare beneficiaries who are not also qualified for full Medicaid coverage, health centers must absorb the cost of subsidizing these uncovered services through their grants. As a result, on a per-patient basis, Medicare payment rates are lower than those received through Medicaid; in 2017, Medicare covered only 58% of charges. Private health insurance is typically the lowest payer, and may pay less for the covered services while also using higher cost sharing and excluding many forms of necessary care. In 2017, private insurance payments covered 56% of the private insurance charges.

| Payer |

2010 |

2017 |

| Medicaid |

81% |

79% |

| Medicare |

66% |

58% |

| Private |

57% |

56% |

| Self-Pay |

21% |

24% |

| Total Patient Charges |

59% |

63% |

| Source: 2010 and 2017 national UDS reports, Table 9D |

Despite a surge in the number of patients served, per-patient Medicaid spending at health centers has grown only modestly. The number of Medicaid patients served by health centers has increased over time, with a significant surge following implementation of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion in 2014. From 2010 to 2017, the number of health center Medicaid patients increased 78% from 7.5 million to 13.3 million (Table 2). During this period, health center Medicaid revenue also nearly doubled, increasing 97% when adjusted for inflation. However, on a per patient basis, health center Medicaid revenue increased a much more modest 11%. This suggests that the growth in health center Medicaid revenue is the result of the increase in the number of patients served rather than per-patient cost escalation. Although the FQHC payment methodology calls for annual medical inflation adjustments, the growth in health center per patient Medicaid revenue is half the cumulative medical inflation rate of 22% over the same period. This slow per-patient spending growth rate at health centers is consistent with other research showing low per capita spending growth changes over time, which attributes overall Medicaid spending growth primarily to increased enrollment.

| |

2010* |

2017 |

Percent Change |

| Total Medicaid patients |

7,505,047 |

13,340,999 |

78% |

| Total Medicaid revenue |

$5,823,933,581 |

$11,477,870,314 |

97% |

| Medicaid revenue per Medicaid patient |

$776 |

$860 |

11% |

| *Nominal revenue amounts for 2010 were inflated to 2017 using the Consumer Price Index, Medical, US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: Medical Care, retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Notes: Medicaid revenue per patient calculated by dividing the Medicaid revenue by the number of Medicaid patients. Source: GW analysis of 2010 and 2017 UDS data. |

What is the role of Section 330 grant funding?

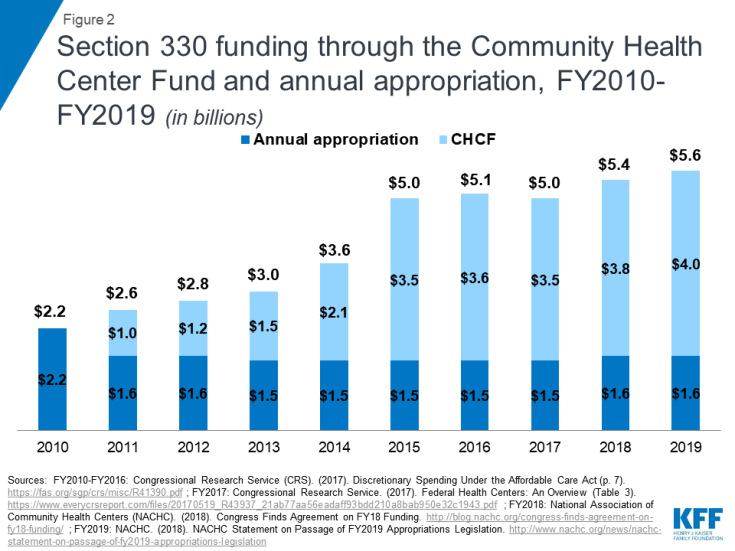

Section 330 funding supports health centers through two funding streams, an annual appropriation and the Community Health Center Fund (CHCF), established by the Affordable Care Act (Table 3). Originally, Section 330 grant funding flowed exclusively through the annual discretionary appropriations process, as part of the overall appropriation made to the Departments of Labor and Health and Human Services. However, in 2010, as part of the Affordable Care Act, Congress created the Community Health Center Fund (CHCF), supported through a special mandatory spending account rather than the normal discretionary process. Both the CHCF and the annual appropriation are subject to all Section 330 requirements. Creating the CHCF effectively split annual health center funding into two pots – one subject to the annual appropriations process, and the other governed by the length of the CHCF authorization, but flowing automatically and without an annual appropriation. The original CHCF was authorized for five years. Because the CHCF is time-limited, Congress has twice extended it for two years, first in 2015 and then again in 2018. The current extension will sunset on September 30, 2019.

| |

Annual Section 330 Grant Appropriation |

Community Health Center Fund |

| Authority |

Discretionary funding; funding amounts determined through the federal appropriations process |

Mandatory funding; funding amounts established through authorizing legislation |

| Duration |

Annual |

Funding period specified in authorizing legislation; usually longer than one year. Current authorization is for two years. |

| Allocation |

Competitive grants, with specified percentages of total funding allocated to health centers serving certain populations:

- 8.6% for serving migrant/seasonal farmworkers

- 8.7% for serving people who are homeless

- 1.2% for serving residents of public housing

|

Competitive grants |

| FY 2019 Funding Amount |

$1.6 Billion |

$4.0 Billion |

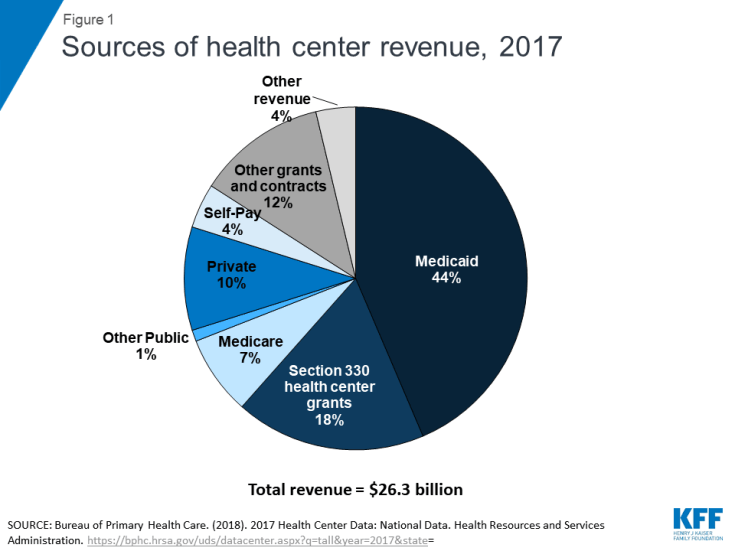

In the nine years since the creation of the CHCF, Section 330 health center funding more than doubled. When the CHCF was first established, it accounted for less than half (40%) of Section 330 funding; however, between FY2011 and FY2019, lawmakers increased funding through the CHCF while holding the annually appropriated amount relatively constant. By fiscal year 2018, the CHCF accounted for 72% of Section 330 grant funding; only 28% came through annual discretionary appropriations. At the same time, the creation of the CHCF, and its subsequent funding increases, contributed to total Section 330 health center funding more than doubling, from $2.2 billion in FY 2010 to $5.6 billion in FY 2019 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Section 330 funding through the Community Health Center Fund and annual appropriation, FY2010-FY2019 (in billions)

In addition to annual grants that support ongoing operations, Section 330 funding also provides health centers with supplemental grants to expand capacity, improve care, and respond to emerging priorities. Over the years, Section 330 funds have supported the opening of new access points in previously unserved communities, expanded access to addiction treatment and recovery or mental health services programs, and enhanced health information technology capability to affiliate with managed care plans or integrated delivery systems such as accountable care organizations. Federal appropriations also have been invested to increase the number of behavioral health care staff and enable health centers to respond to public health crises such as the hurricanes in Puerto Rico and Houston, and the Zika virus. In this way, grants are critical not only because they fund ongoing care for uninsured populations and services, but also because they supply health centers with the working capital needed to expand capacity and services that providers that do not serve poor communities typically would find from private investors and lenders.

Section 330 funding can also be used to advance policy priorities. As part of the recently announced goal to end the HIV/AIDS epidemic by 2030, one strategy will be to grow health center capacity to find and treat patients in the nation’s most vulnerable communities, who are at risk for or living with HIV/AIDS. Health centers serve an estimated one in five people living with HIV who are receiving care for their condition. The administration has explicitly identified health centers as key to its response and has proposed dedicating $50 million in health center grant funding to expand access to prophylactic HIV treatment (PrEP) along with expanded HIV/AIDS services, outreach and care coordination as part of the President’s FY 2020 budget.

How have funding changes affected health centers?

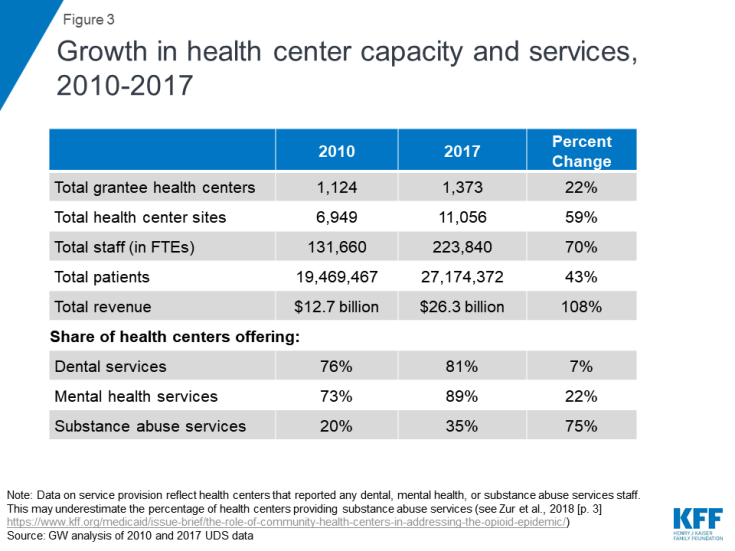

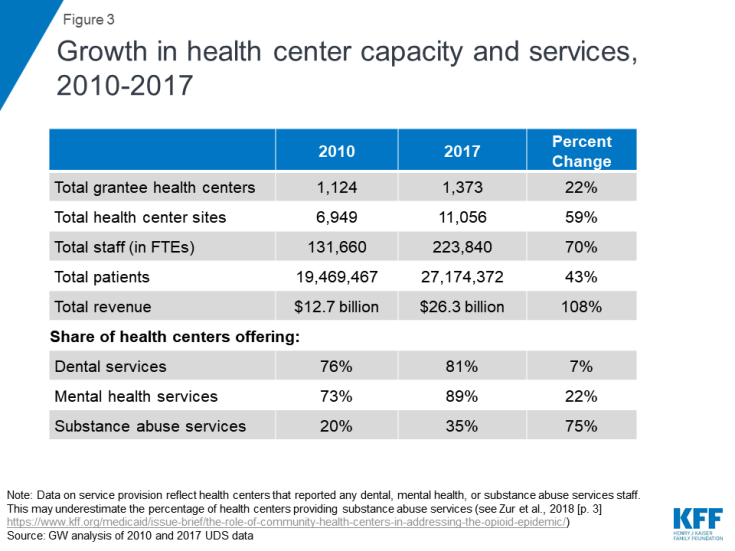

Funding increases have spurred health center growth, expanding access to needed services for vulnerable populations. The revenue increases flowing from the combination of broader Medicaid and private insurance coverage and increased grant funding under the CHCF have enabled health centers to increase their reach, staffing, and the scope of the services they offer. In 2010, a total of 1,124 health center grantees operated in 6,949 sites; by 2017, total grantees had grown to 1,373 and total operating sites reached 11,056 (Figure 3). Total health center staffing stood at 131,660 full-time equivalents (FTEs) in 2010; by 2017, this figure had grown to 223,840.This growth translated into greater service capacity, not simply more patients. From 2010 to 2017, the share of health centers providing mental health services increased by 22%, while the share offering substance use disorder services grew by 75%. The share of health centers offering dental health services also increased over this same period, but by a more modest 7%. In 2010, health centers served 19.5 million patients on a total operating revenue base of $12.7 billion; by 2017, this figure had grown to 27.2 million patients on a total revenue base of $26.3 billion.

Figure 3: Growth in health center capacity and services, 2010-2017

Looking Ahead

Health centers have become a significant part of the health care landscape in medically underserved communities across the nation, both as a major source of primary care health and increasingly, as entry points into care for patients with more complex health needs. Consistent with the original vision of how health centers could be sustained over time, today’s health centers receive their principal support through Medicaid payments and grant funding. Together these two funding sources cover the cost of care to Medicaid-insured patients, enable health centers to make needed care available to uninsured patients, and help underinsured patients meet out-of-pocket costs for uncovered services and high cost-sharing they otherwise could not afford. Other sources of grant and insurance funding enable health centers to target key populations and services, but Medicaid and Section 330 grants are the mainstay.

The success and durability of the health centers model can be seen in the many roles health centers play in the health care system. They are on the front lines of the opioid epidemic. They are an important source of care during natural disasters, such as hurricanes, and public health threats, such as the Zika virus. They are a key element in the national effort to halt the spread of HIV. And, they serve as a model for the design of health homes that integrate behavioral health and physical health care. Sustainable financing through Medicaid and Section 330 grants is essential to ensuring that health centers will be able to continue to fill these important roles.

Because the stable financing of health centers is key to their long-term performance, an important policy question Congress will consider this year is whether to extend the life of the CHCF and if so, for how long. The original fund was authorized for five years, but since 2015, the CHCF has been extended in two-year cycles, with the current authorization set to expire on September 30, 2019. Since the CHCF now represents over 70% of Section 330 health center grant funding, establishing a longer funding period has emerged as a significant factor enabling health centers to continue as a key resource and flexible tool for responding to emerging population health needs.

Additional funding support for this brief was provided to the George Washington University by the RCHN Community Health Foundation.