Medicaid Authorities and Options to Address Social Determinants of Health

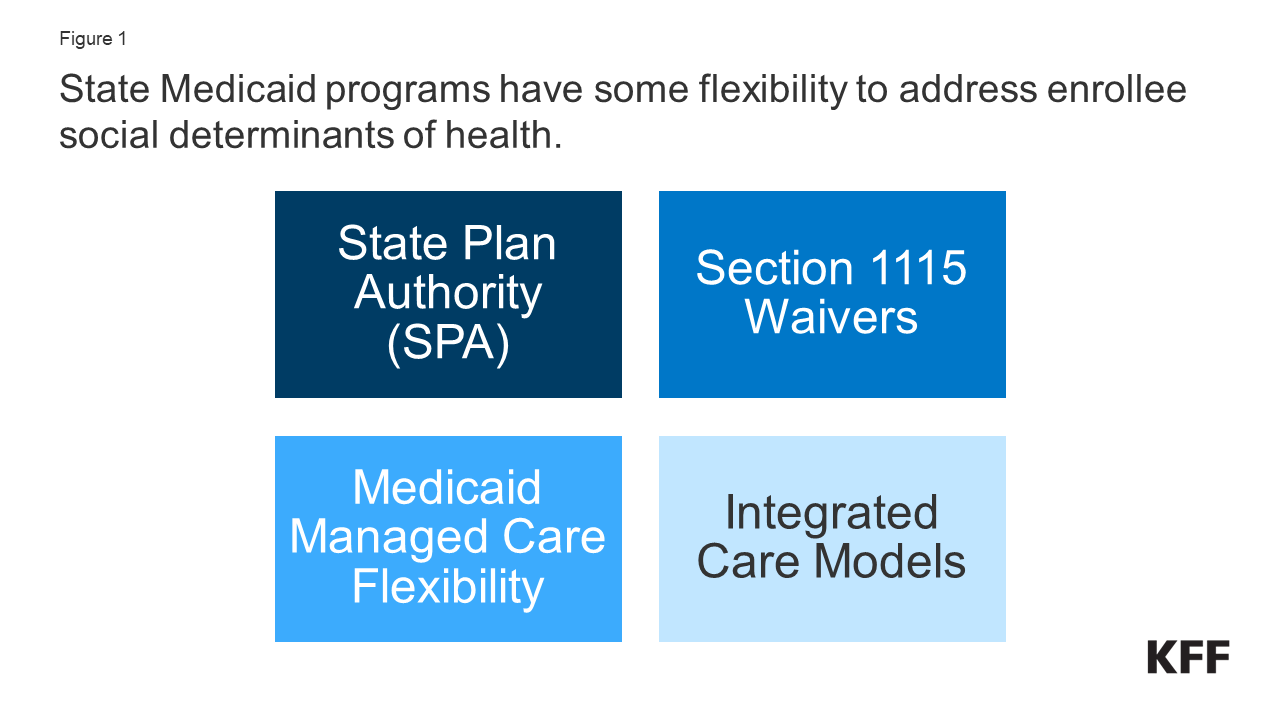

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age. While there are limits, states can use Medicaid – which, by design, serves a primarily low-income population with greater social needs – to address social determinants of health. To expand opportunities for states to use Medicaid to address health-related social needs, The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services or CMS announced new flexibilities available to states through managed care and through Section 1115 demonstration waivers. New CMS guidance accompanies the Biden-Harris Administration’s release of the U.S. Playbook to Address Social Determinants of Health and HHS’s Call to Action to Address Health-Related Social Needs. While health programs like Medicaid can play a supporting role, CMS stresses the new HRSN initiatives are not designed to replace other federal, state, and local social service programs but rather to complement and coordinate with these efforts. The resources provided to date through Medicaid are relatively modest in comparison to the social needs that exist. This brief outlines the range of Medicaid authorities and flexibilities that can be used to add benefits and design programs to address the social determinants of health (Figure 1).

Figure 1: State Medicaid programs have some flexibility to address enrollee social determinants of health.

What Are Social Determinants of Health?

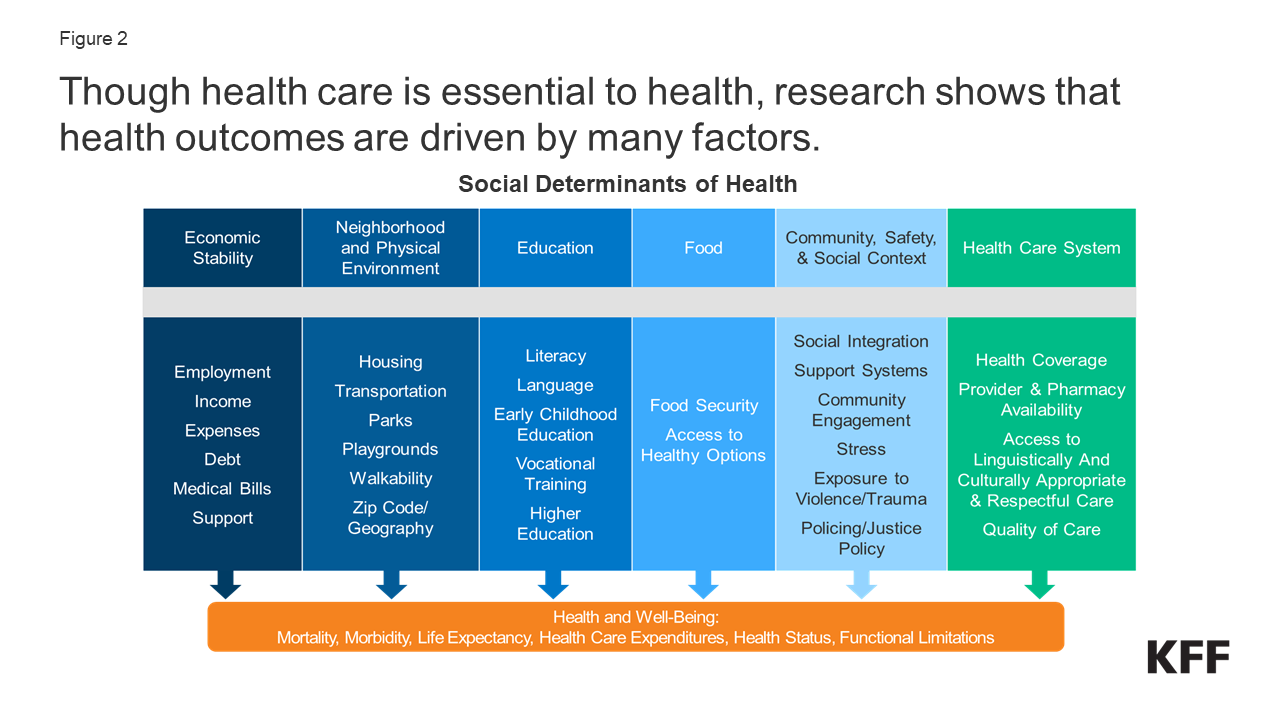

Social determinants of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age.1 They include factors like economic stability, education, neighborhood and physical environment, employment, and social support networks, as well as access to health care (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Though health care is essential to health, research shows that health outcomes are driven by many factors.

Though health care – and, by extension, health coverage – is essential to health, research shows that health outcomes are driven by an array of factors, including underlying genetics, health behaviors, social, economic, and environmental factors. While there is currently no consensus in the research on the magnitude of the relative contributions of each of these factors to health, studies suggest that health behaviors and social and economic factors are primary drivers of health outcomes, and social, and economic factors can shape individuals’ health behaviors. There is extensive research that concludes that addressing social determinants of health is important for improving health outcomes and reducing health disparities.2

Both health and non-health sectors have been engaged in initiatives to address social determinants of health. Outside of the health care system, non-health sector initiatives seek to shape policies and practices in ways that promote health and health equity. Within the health care sector, a broad range of initiatives have been launched at the federal, state, and local levels and by plans and providers to address social determinants of health, including efforts within Medicaid.

How Can Medicaid be Used to Address Social Determinants of Health?

State Medicaid programs can add certain non-clinical services to home and community-based services (HCBS) programs to support seniors and people with disabilities. Generally, states have not been able to use federal Medicaid funds to pay the direct costs of non-medical services like housing and food.3 However, within Medicaid, states can use a range of state plan and waiver authorities (e.g., 1905(a), 1915(i), 1915(c), or Section 1115) to add certain non-clinical services to the Medicaid benefit package including case management, housing supports, employment supports, and peer support services. Historically, non-medical services have been included as part of Medicaid home and community-based services programs for people who need help with self-care or household activities as a result of disability or chronic illness.

Outside of Medicaid HCBS authorities, state Medicaid programs have historically had more limited flexibility to address social determinants of health. Certain options exist under Medicaid state plan authority as well as Section 1115 authority to add non-clinical benefits. Additionally, under federal Medicaid managed care rules, managed care plans have some flexibility to pay for non-medical services. Other Medicaid payment and delivery system reforms, like the formation of Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), may provide flexibility or opportunities to cover non-medical services that support health as well.

To expand opportunities for states to use Medicaid to address health-related social needs, CMS announced new flexibilities available to states through Medicaid managed care authority and through Section 1115 demonstration waivers. CMS defines health-related social needs (or “HRSN”) as an individual’s unmet, adverse social conditions (e.g., housing instability, homelessness, nutrition insecurity) that contribute to poor health and are a result of underlying social determinants of health. New CMS guidance builds on guidance released in 2021. The remaining sections outline the primary Medicaid authorities and flexibilities that can be used to add benefits and design programs to address the social determinants of health beyond HCBS programs. Some efforts may address a single issue (e.g., housing, or food security) while other efforts and initiatives are designed to address a range of social determinants of health.

Medicaid Managed Care Plan Authority

With over two-thirds of Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in comprehensive, risk-based managed care plans nationally, health plans can be an important part of efforts to address enrollee social determinants of health. States pay Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) a set per member per month payment for the Medicaid services specified in their contracts. Capitation rates provide upfront fixed payments to plans for expected utilization of covered services, administration costs, and profit.

Under federal Medicaid managed care rules, Medicaid MCOs can be given flexibility to pay for non-medical services through “in-lieu-of” authority. States may allow Medicaid MCOs the option to offer (and provide beneficiaries the option to receive) services or settings that substitute for standard Medicaid benefits (referred to as “in lieu of” services (or “ILOS”)) if the substitute service is medically appropriate and cost-effective. For example, a state could authorize in-home prenatal visits for at-risk pregnant beneficiaries as an alternative to traditional office visits or services provided by peer supports, as an alternative to psychosocial rehabilitation services for members with behavioral health needs. The costs of the ILOS are built into managed care rates. In January 2023, CMS released guidance that paves the way for states to allow Medicaid MCOs to offer services, like housing and nutrition supports, as substitutes for standard Medicaid benefits.4 The new guidance establishes financial guardrails and new requirements for ILOS and clarifies these substitute services can be preventive in nature instead of an immediate substitute (e.g., providing a dehumidifier to an individual with asthma before emergency care is needed). This guidance follows the approval of a California proposal to use ILOS. In May 2023, the Biden administration issued a proposed rule related to managed care access, finance, and quality. In the proposed rule, CMS seeks to codify its January 2023 ILOS guidance.5 KFF’s 2023 survey of state Medicaid directors found few states permitted MCOs to cover SDOH-related services (e.g., housing, food, or other) as ILOS as of July 2023.

Under federal rules, Medicaid MCOs can pay for non-medical services as “value-added” services. “Value-added” services are extra services MCOs voluntarily provide outside of covered contract services. These services cannot be built into managed care rates.6 Examples include safe sleeping spaces for infants, repairs and cleaning services to reduce asthma triggers, installation of a shower grab bar, and health play and exercise programs.

States may implement MCO procurement and contracting strategies, including quality requirements linked to SDOH.7 In a 2023 KFF survey of Medicaid directors, most MCO states reported leveraging Medicaid MCO contracts to promote at least one strategy to address social determinants of health in FY 2023 (Figure 3). More than half of MCO states reported requiring MCOs to screen enrollees for social needs, screen enrollees for behavioral health needs, provide referrals to social services, and partner with community-based organizations (CBOs). Fewer states reported requiring MCO community reinvestment (i.e., directing plans to reinvest a portion of revenue or profits into the communities they serve) compared to other strategies. States can use incentive payments or quality withhold arrangements to reward plans for investments and/or improvements in SDOH. For example, states may provide incentive payments to plans that screen enrollees for social needs or make other strategic investments in addressing health-related social needs or incentive payments to improve or maintain quality while lowering costs. Additionally, many plans have developed initiatives and engaged in activities to address enrollees’ social needs beyond state requirements; however, it is difficult to compile national data to reflect this.

In the Institute for Medicaid Innovation’s 2023 Medicaid managed care survey, plans indicated state Medicaid agencies could support MCO efforts to address enrollee social needs by improving data sharing (e.g., between the state and MCOs and between government agencies), increasing financial resources (including to support the facilitation of partnerships and new payment models), and facilitating contracting with CBOs.

States can direct managed care plans to make payments to their network providers to further state goals and priorities, including those related to addressing social determinants of health. States can seek CMS approval to require MCOs to implement value-based purchasing models for provider reimbursement (e.g., pay for performance, bundled payments) or participate in multi-payer or Medicaid-specific delivery system reform or performance improvement initiatives. For example, a state may require managed care plans to implement alternative payment models (APMs) or incentive payments to encourage providers to screen for socioeconomic risk factors.

Section 1115 Waivers

Through Section 1115 authority, states can test approaches for addressing SDOH including requesting federal matching funds to test SDOH related services and supports in ways that promote Medicaid program objectives. Section 1115 waivers generally reflect priorities identified by states and CMS, as well as changing priorities from one presidential administration to another. While not required by statute, longstanding policy requires that Section 1115 waivers be budget neutral for the federal government. As outlined in CMS’s 2021 guidance, states can request federal matching funds through Section 1115 to test the effectiveness of providing SDOH-related services and supports. States can also test alternative payment methodologies designed to address SDOH under Section 1115 authority. Prior to the Biden administration announcement of new HRSN waiver flexibilities (discussed in more detail below), a number of states had approved Section 1115 waivers that aimed to address enrollee social determinants of health. These SDOH waivers were generally narrow in scope (services and target populations) or pilot programs targeting specific regions. For example, in October 2018, CMS approved North Carolina’s Healthy Opportunities Pilots that operate in three geographic regions of the state and provide services to address enrollee needs related to housing, food, transportation, and interpersonal safety. Some waivers allowed MCOs or ACOs flexibility to offer health-related services but stopped short of requiring them to do so.

In December 2022, CMS announced a Section 1115 demonstration waiver opportunity to expand the tools available to states to address HRSN. In November 2023, CMS issued a detailed Medicaid and CHIP HRSN Framework accompanied by an Informational Bulletin (CIB). HRSN services that will be considered under the new framework include housing supports, nutrition supports, and HRSN case management (and other services on a case-by-case basis) (Figure 4). As of January 2024, CMS has approved Section 1115 demonstrations in eight states (Arizona, Arkansas, California, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, and Washington) that authorize evidence-based HRSN services for specific high-need populations. Approvals include coverage of rent/temporary housing and utilities for up to 6 months and meal support up to three meals per day (up to 6 months). HRSN services must be medically appropriate (using state-defined clinical and social risk factors) and voluntary for enrollees. States can add HRSN services to the benefit package and may require managed care plans to offer the services to enrollees who meet state criteria. Federal expenditures are also available to build the capacity of community based HRSN providers that may require technical assistance and infrastructure support to become Medicaid providers. Additionally, the Biden administration has expressed support for “community care hubs” (or similar models) that focus on aligning health and social care and may facilitate care coordination as well as develop, manage, and support a network of CBOs.

CMS guidance specifies spending for HRSN cannot exceed 3% of total annual Medicaid spend. CMS indicates HRSN spending will not require offsetting savings (that may otherwise be required for services authorized/financed under Section 1115). State spending on related social services (before the waiver) must be maintained or increased. To strengthen access, states must also meet minimum provider payment rate requirements for primary care, behavioral health, and obstetrics services. HRSN services are subject to monitoring and evaluation requirements, including reporting on quality and health equity measures. In November 2023, HHS and HUD announced the launch of a new learning collaborative that will support states with the implementation of Section 1115 housing-related supports, including helping states improve collaboration and coordination between organizations and systems that provide housing services.

State Plan Authority & Delivery System Reform Models

States may elect to include optional benefits that address social determinants under Section 1905(a) State Plan authority. For example, states may include rehabilitative services, including peer supports and/or case management (or “targeted” case management8) services, under their Medicaid state plan. States that choose to offer these services frequently target services based on health or functional need criteria. Peer supports can help individuals coordinate care and social supports and services, facilitating linkages to housing, transportation, employment, nutrition services, and other community-based supports. Case management services can also assist individuals in gaining access to medical, social, educational, and other services. Case management services are frequently an important component of HCBS programs but can also be used to address a broader range of enrollee needs.

States can provide broader services to support health through the optional health home state plan benefit option established by the ACA. Under this option (Section 1945), states can establish health homes to coordinate care for people who have chronic conditions. Health home services include comprehensive care management, care coordination, health promotion, comprehensive transitional care, patient and family support, as well as referrals to community and social support services (such as housing, transportation, employment, or nutritional services). States receive a 90% federal match rate for qualified health home service expenditures for the first eight quarters under each health home.9,10 A federally funded evaluation of the Health Homes model found that most providers reported significant growth in their ability to connect patients to nonclinical social services and supports under the model, but that lack of stable housing and transportation were common problems for many enrollees that were difficult for providers to address with insufficient affordable housing and rent support resources.11

Integrated care models, including patient-centered medical home (PMCHs) and Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), often emphasize person-centered, comprehensive care and typically involve partnerships with community-based organizations and social services agencies. 12 Integrated care models might address social determinants of health through interdisciplinary care teams or care coordination services. Payment mechanisms tied to these models (e.g., per member per month payments (with or without quality or cost incentives) or shared savings/risk models with quality requirements) may provide incentives for providers to address the broad needs of Medicaid beneficiaries.

Looking Ahead

While health programs like Medicaid can play a supporting role, guidance from CMS stresses the new HRSN initiatives are not designed to replace other federal, state, and local social service programs but rather to complement and coordinate with these efforts. The resources provided through Medicaid to address social determinants of health are relatively modest in the face of the social needs that exist, and there is ongoing debate over how effectively the health care system can meet these needs.

Areas to watch include which health-related services states may gain approval to integrate under managed care authority and/or Section 1115, how states define target populations, and how CMS and states negotiate budget neutrality terms (an issue that Republican members of the US House Energy and Commerce have raised concerns about).

States that have not pursued but may be interested in new HRSN flexibilities can learn from the implementation experience of early adopters, including how states and plans work with community-based organizations and coordinate with federal, state, and local social service programs. While there is some evidence, 13,14,15,16,17 ILOS and Section 1115 monitoring and evaluation reports may yield new data involving how addressing certain enrollee social needs may impact health care utilization, spending, and health outcomes. Finally, whether states can sustain funding streams for HRSN longer term and how future changes in Administration may affect states’ ability to pursue these initiatives through waivers will be important to watch.

Endnotes

World Health Organization, “Social Determinants of Health,” accessed January 8, 2024 https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Healthy People 2030: Social Determinants of Health, Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health

Federal financial participation is not available to state Medicaid programs for room and board except in certain medical institutions, as codified in multiple regulatory provisions. See, for example, 42 CFR § 441.310(a)(2) and 42 CFR §441.360(b). CMS defines board as three meals a day or any other full nutritional regimen, and room as hotel or shelter type expenses including all property related costs such as rental or purchase of real estate and furnishings, maintenance, utilities, and related administrative services. See section 4442.3 of the State Medicaid Manual at www.cms.gov/regulations-andguidance/guidance/manuals/paper-based-manuals-items/cms021927.

An ILOS must not violate any applicable federal requirements, including general prohibitions on payment for room and board under title XIX of the Social Security Act.

Medicaid Program; Medicaid and Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Managed Care Access, Finance, and Quality, 88 FR 28092 (May 3, 2023) (to be codified at 42 CFR 430, 42 CFR 438, 42 CFR 457)

Costs associated with value-added services are included in the numerator of the MLR calculation (either as incurred claims or quality-related activities).

If managed care plans implement SDOH activities that meet certain federal requirements (in 45 CFR § 158.150(b) and are not excluded under 45 CFR § 158.150(c)), managed care plans may include the costs associated with these activities in the numerator of the MLR as activities that improve health care quality (under 42 CFR § 438.8(e)(3)).

When states provide case management services under the state plan without regard to “statewideness” and “comparability” requirements, the benefit is referred to as “targeted case management.”

States can (and have) created more than one Health Home program to target different populations.

For SUD health homes approved on or after October 1, 2018, states can receive ten quarters of enhanced federal match.

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), Evaluation of the Medicaid Health Home Option for Beneficiaries with Chronic Conditions: Evaluation of Outcomes of Selected Health Home Programs Annual Report - Year Five, Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, May 2017, https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/evaluation-medicaid-health-home-option-beneficiaries-chronic-conditions-evaluation-outcomes-selected-health-home-programs-annual-report-year-five

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Integrated Care Models, Baltimore, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, July 2012, https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/SMD-12-001.pdf

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Integrated Care Models, Baltimore, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, July 2012, https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/smd-12-002.pdf

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), Building the Evidence Base for Social Determinants of Health Interventions, Washington DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, May 2021, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/e400d2ae6a6790287c5176e36fe47040/PR-A1010-1_final.pdf

The Commonwealth Fund, “Review of Evidence for Health-Related Social Needs Interviews,” accessed December 8, 2023, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/2022-09/ROI_calculator_evidence_review_2022_update_Sept_2022.pdf

Emilie Courtin et al., “Can Social Policies Improve Health? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 38 Randomized Trials,” The Milbank Quarterly 98 (June 2020), https://www.milbank.org/quarterly/articles/can-social-policies-improve-health-a-systematic-review-and-meta%E2%80%90analysis-of-38-randomized-trials/

Hannah L Crook et al., “How Are Payment Reforms Addressing Social Determinants of Health? Policy Implications and Next Steps,” Milbank Memorial Fund (February 2021), https://healthpolicy.duke.edu/sites/default/files/2021-02/How%20Are%20Payment%20Reforms%20Addressing%20Social%20Determinants%20of%20Health.pdf

Lauren M. Gottlieb, Holly Wing, and Nancy E. Adler, “A Systematic Review of Interventions on Patients' Social and Economic Needs,” American Journal of Preventative Medicine 53 no. 5 (July 2017): 719-729, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28688725/