Streamlining Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services: Key Policy Questions

Introduction

In the early decades of the Medicaid program, institutional care was the dominant form of long-term services and supports (LTSS), with home and community-based services (HCBS) becoming increasingly available over time. State Medicaid programs are required to cover nursing facility services, while most HCBS are provided at state option. This effectively establishes an institutional bias within the Medicaid program, which federal and state policymakers have been working to address in recent decades. Since the early 1980s, Congress has amended federal Medicaid law numerous times, seeking to ameliorate the program’s institutional bias by creating new authorities and incentives for states to offer HCBS. These initiatives have resulted in a patchwork of options, each with its own review and approval processes, financial and functional eligibility criteria, available services, reporting requirements, quality measures, and other features.

While substantially increasing beneficiary access to HCBS over the last several decades, this piecemeal approach has contributed to administrative complexity for states. To provide services to a variety of populations, states combine multiple authorities, administer different sets of eligibility rules, and oversee distinct quality measures for each HCBS option. States also face fiscal pressures that drive a desire to control costs by limiting program enrollment and/or placing utilization controls on services.

The current Medicaid HCBS system also creates confusion for individuals in need of services. Those seeking services for the first time are typically unfamiliar with the program’s complexities and may have to navigate different sets of requirements and determine which pathway leads to the benefit package that best meets their needs. One benefit package may include supports such as personal care targeted to people with physical limitations, while specialty behavioral health services may be available through a separate benefit package. If different services are offered through distinct programs, people with multiple needs may have to choose which services to pursue and which to forgo.

Recently, policymakers have begun discussing how states and beneficiaries might be helped by a streamlined Medicaid state plan authority that consolidates features of the various existing HCBS options. The President’s FY 2016 and FY 2017 budgets both proposed an eight year pilot program for up to five states to create a comprehensive Medicaid state plan option that would provide equal access to institutional care and HCBS, seeking to end institutional bias and simplify state administration.1 In February, 2016, the Bipartisan Policy Center released initial recommendations to improve long-term care financing, which include combining the various existing Medicaid HCBS authorities into a single streamlined state plan option to incentivize states to expand HCBS.2 Also in February, 2016, the Long-Term Care Financing Collaborative issued a consensus framework for long-term care financing reform, which proposes changes related to Medicaid LTSS eligibility and financing.3 This issue brief draws on features of existing Medicaid HCBS programs from the last 35 years and identifies key policy questions raised by initiatives to streamline Medicaid HCBS, ameliorate institutional bias, and promote administrative simplification.

Background

The Need for HCBS

HCBS help people with functional limitations meet self-care and household activity needs and gain access to and engage in their communities. These services are used by people of all ages with a range of disabilities and chronic conditions.4 People who need HCBS include those with physical disabilities such as multiple sclerosis or spinal cord injuries, cognitive disabilities such as dementia, intellectual or developmental disabilities (I/DD) such as Down’s syndrome or autism, and behavioral health disabilities such as serious mental illness. HCBS include a range of services, such as habilitative services, adult day health care programs, home health aide services, personal care services, assistive technology, and case management services.5

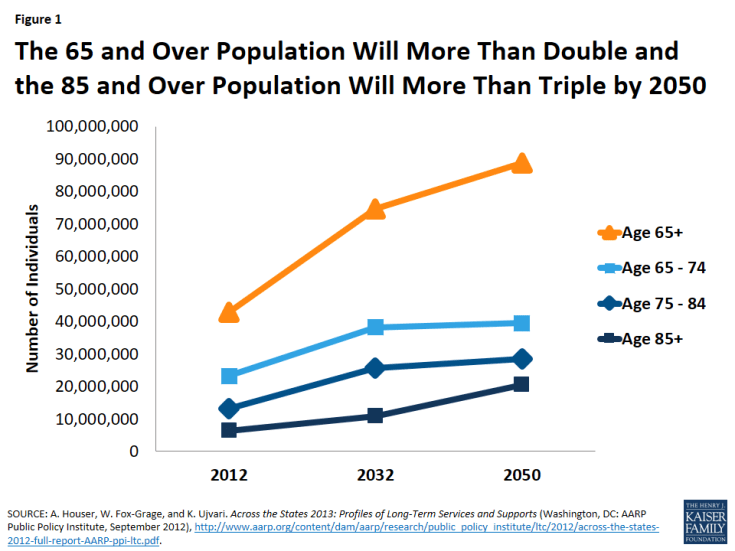

With impending demographic shifts in the U.S., the need for HCBS is expected to increase exponentially over the coming decades. Population estimates project that the number of people over age 65 will more than double, and the number of people over age 85 will more than triple by 2050 (Figure 1). Just under half (46%) of seniors living in the community report that they need assistance with self-care or household activities.6 This population is at risk of institutionalization if their needs are not adequately supported in the community. About one-third (32%) of this group may have dementia, adding further complexity to meeting their needs.7 In addition, one-third of seniors who have LTSS needs live alone,8 making it less likely that family caregivers are available to meet all of their needs.

Figure 1: The 65 and Over Population Will More Than Double and the 85 and Over Population Will More Than Triple by 2050

In addition to supporting seniors with functional limitations, HCBS play an important role for non-elderly people with disabilities living in the community. Advances in medical science and technology are enabling many people with disabilities to live longer and more independently than ever before. As of 2010, nearly 57 million people, or 18.7% of people living in the community, have some type of disability, such as a communication, mental, or physical limitation.9 Over 38 million people, or 12.6% of those living in the community, have a disability that is considered severe.10 Forty percent of working age adults with a disability were employed in 2010, compared to nearly 80% of working age adults without disabilities.11 HCBS are essential to helping people with disabilities move from institutions to the community. These services also can be used to prevent institutionalization by providing appropriate supports in the community that delay or avoid further declines in functioning. Additionally, HCBS help ensure that people with disabilities are fully integrated into community life by providing services like supported housing and supportive employment.12

Medicaid’s Role in Financing HCBS

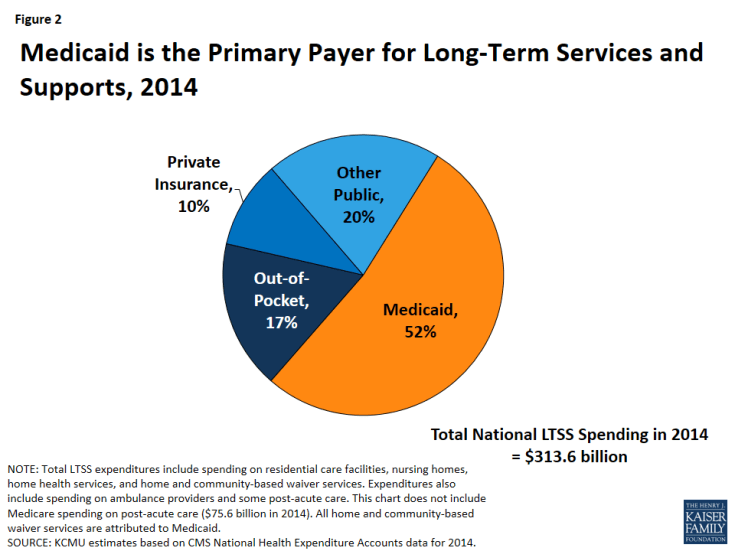

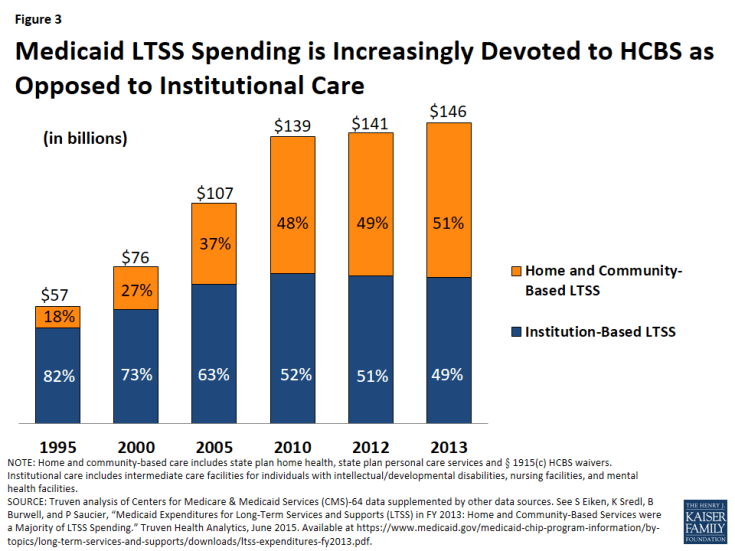

In addition to covering medical care, Medicaid has developed into the nation’s single largest payer for both institutional and community-based LTSS, funding over half of these services in 2014 (Figure 2). As federal and state policymakers continue to develop reforms to overcome the institutional bias built into the law, the share of Medicaid LTSS spending devoted to HCBS instead of institutional care has been steadily increasing in recent decades (Figure 3). This development has been spurred by beneficiary preferences for HCBS, the typically lower cost of HCBS relative to institutional care, and the Supreme Court’s 1999 Olmstead decision, which found that the unjustified institutionalization of people with disabilities is discrimination under the Americans with Disabilities Act.13

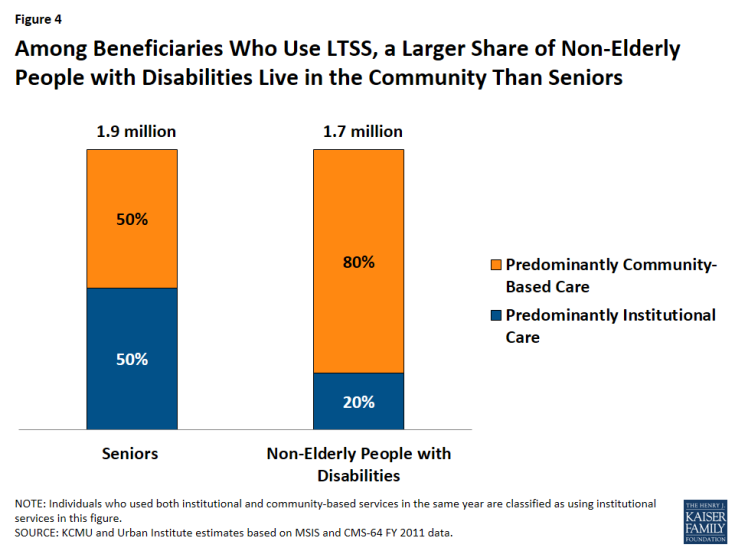

While 2013 marked the first time that the share of Medicaid LTSS spending devoted to HCBS exceeded the share devoted to institutional spending, access to HCBS is inconsistent among beneficiary populations. Among Medicaid beneficiaries receiving LTSS, 80 percent of non-elderly people with disabilities lived in the community in 2011, while only half of seniors did so (Figure 4). For people with I/DD, the share of Medicaid LTSS dollars devoted to HCBS exceeded the share spent on institutional care as early as 2002,14 over a decade before the Medicaid LTSS spending balance for all populations tipped toward HCBS. With substantial shares of Medicaid beneficiaries who use LTSS remaining in institutions and variation among states and populations, the need to continue to increase access to HCBS remains.

Figure 4: Among Beneficiaries Who Use LTSS, a Larger Share of Non-Elderly People with Disabilities Live in the Community Than Seniors

Existing Medicaid HCBS Authorities

An institutional bias remains inherent in the Medicaid statute. Since the program’s inception in 1965, Medicaid has required states to cover nursing facility services to address the LTSS needs of seniors and people with disabilities. Authority to cover intermediate care facility services for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (ICF/ID) was added in 1971; while ICF/ID services are optional, all states cover the ICF/ID benefit. By contrast, most Medicaid HCBS (with the exception of home health services) are provided at state option.

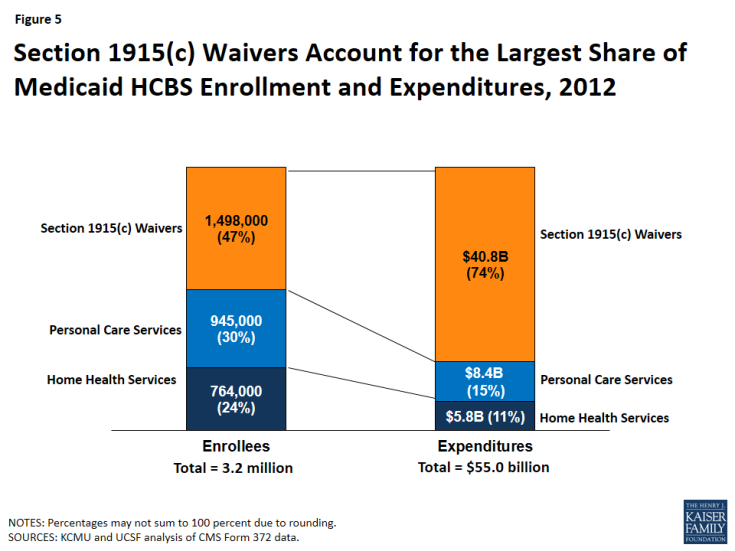

Over the last 35 years, Congress has amended federal Medicaid law numerous times, creating a patchwork of options for states to offer HCBS (Table 1).15 Some of these authorities are permanent, while others have been time-limited programs. The earliest of these efforts was the addition of authority for HCBS waivers through Section 1915(c) of the Social Security Act in 1981, and this program remains the primary vehicle through which states deliver HCBS today (Figure 5). These waivers authorize states to provide services that are non-medical in nature, such as personal care services, adult day health services, habilitation services, and respite care, to beneficiaries who would otherwise require institutional care. As of 2012, nearly 300 of these waivers in 47 states and DC served 1.5 million beneficiaries.16 Unlike services provided through Medicaid state plan authorities, waiver enrollment can be capped; as of 2014, over 580,000 people in 39 states were waiting for Medicaid home and community-based waiver services.17 States also provide HCBS through Medicaid state plan authorities: in 2012, 764,000 beneficiaries in 50 states and DC received home health services and 945,000 beneficiaries in 32 states received personal care services through the state plan option.18

Figure 5: Section 1915(c) Waivers Account for the Largest Share of Medicaid HCBS Enrollment and Expenditures, 2012

Most recently, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) offered states new and expanded options to provide HCBS.19 These include an amended version of the Section 1915(i) HCBS state plan option and the creation of the Community First Choice (CFC, or Section 1915(k)) state plan option. Section 1915(i) enables states to offer HCBS as part of the state plan benefit package instead of through a waiver. The service options are the same as those available under Section 1915(c) waivers but unlike waivers, can be provided to beneficiaries with functional limitations that are less stringent than what is required for an institutional level of care. This means that states can offer HCBS through Section 1915(i) as preventive services to avoid or delay the need for more intensive or costly services in the future. Many states use Section 1915(i) to target services to specific populations, such as people with significant mental health needs. Seventeen states include Section 1915(i) services in their Medicaid state plan benefit package as of October 2015,20 and five states reported plans to implement Section 1915(i) in FY 2016.21 CFC allows states to provide attendant care services and supports and receive six percent enhanced federal matching funds. Five states have adopted CFC as of December 2015,22 and four states reported plans to implement CFC in FY 2016.23

Other HCBS authorities have fallen out of use or are not used by any states. For example, although nearly all states offer beneficiaries the ability to self-direct their services, few states presently use the Section 1915(j) option to authorize self-directed personal care services because these features are now available through other Medicaid authorities. Only one state uses Section 1929 waiver authority to offer HCBS, without full Medicaid benefits, to seniors with functional disabilities.24 No state uses Section 1915(d) waiver authority for seniors who require institutional care or Section 1915(e) waiver authority for young children with HIV or drug dependency at birth who are receiving adoption or foster care assistance.

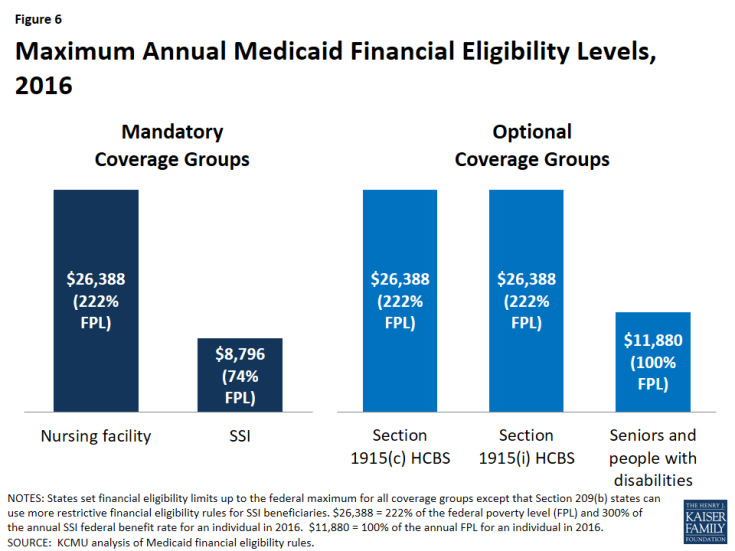

States can choose to extend eligibility for most HCBS up to a federal maximum of 300% of the federal benefit rate for Supplemental Security Income (SSI, $26,388 per year for an individual in 2016) (Figure 6).25 This maximum applies to Section 1915(c) HCBS waivers, the Section 1915(i) HCBS state plan option, and CFC attendant care services and supports. Under the Section 1915(i) state plan option, states can choose to cover people up 150% FPL ($17,820 per year for an individual in 2016), including those who are not otherwise eligible for Medicaid, and/or people who would be eligible for Medicaid through an existing HCBS waiver with income below 300 percent of SSI. Financial eligibility for CFC goes up to 150% FPL with an additional state option to provide services to people above 150% FPL, up to the state’s income limit for nursing facility services (which could be as high as 300% of SSI).

The maximum financial eligibility limits for traditional Medicaid state plan services, which include some HCBS such as home health and personal care, are lower (Figure 6). Seniors and people with disabilities who qualify for SSI (75% FPL, or $8,796 per year in 2016) automatically receive Medicaid in most states.26 As of 2015, 21 states have opted to expand eligibility for seniors and people with disabilities beyond the SSI limit, up to a federal maximum of 100% FPL ($11,880 per year for an individual in 2016).27 In states that have adopted the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, non-elderly people with disabilities may qualify as expansion adults up to 138% FPL ($16,394 per year for an individual in 2016).28

States generally retain the option to use asset limits in disability-related pathways, although the newer Section 1915(i) independent pathway to Medicaid eligibility does not include an asset test. Most states apply asset limits to eligibility pathways associated with HCBS. They generally use the SSI program limits of $2,000 for an individual and $3,000 for a couple. An exception is the Section 1915(i) authority, which as amended by the ACA, allows states to create a new coverage group with access to full Medicaid state plan benefits and state plan HCBS without an asset limit for people with incomes up to 150% FPL.29

| Table 1: Selected Social Security Act Provisions Authorizing Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services | |||||||

| Provision | Type of Authority: | Description | Enrollment Cap Allowed: | Financing | State Take-Up | ||

| State Plan Option | Waiver | Yes | No | ||||

| Section 1915(c) | X | Expands financial eligibility using institutional rules and authorizes HCBS for people who need institutional level of care | X | Requires federal cost neutrality | As of 2012, nearly 300 waivers in 47 states and DC serve 1.5 million beneficiaries | ||

| Section 1915(d) | X | Authorizes HCBS for seniors who need institutional level of care | X | Complex cost test required | No state uses | ||

| Section 1915(e) | X | Authorizes HCBS for children under age 5 receiving federal adoption or foster care assistance and who have AIDS or were drug-dependent at birth and likely to require institutional level of care | X | No state uses | |||

| Section 1915(i) | X | Authorizes the same HCBS as available under Section 1915(c) waivers. Requires less than institutional level of care. Services can be targeted to populations. | X* | As of Oct. 2015, 17 states adopted | |||

| Section 1915(j) | X | Authorizes self-directed personal care services. | X | As of 2014, 5 states use** | |||

| Section 1915(k) | X | Authorizes attendant care services and supports for people who need institutional level of care | X | 6% enhanced FMAP | As of Dec. 2015, 5 states adopted | ||

| Section 1929 | X | Authorizes HCBS (but not full Medicaid state plan benefits) for functionally disabled seniors | X | Used by 1 state (TX) | |||

| Section 1930 | X | Authorized HCBS for people with I/DD, did not tie eligibility to institutional level of care | X | Provision expired, was used by 8 states for less than 5 years | |||

| Section 1115 | X | Allows HHS Secretary to approve experimental, pilot or demonstration projects that further purposes of Medicaid program. | X | Must be budget neutral to federal government | As of 2014, 12 states use these waivers to deliver HCBS through capitated managed care | ||

| NOTES: *Under § 1915(i), states can constrict functional eligibility criteria if their projected number of individuals expected to receive services is exceeded. **Most states offer self-directed HCBS through authorities other than § 1915(j). SOURCES: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Medicaid Home and Community-based Services Programs: 2012 Data Update (Nov. 2015); State Health Facts, Section 1915(i) Home and Community-based Services State Plan Option (Oct. 2015); State Health Facts Section 1915(k) Community First Choice State Plan Option (Dec. 2015); Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Key Themes in Capitated Managed Long-Term Services and Supports Waivers (Nov. 2014); Jane, K., Traylor, C., Ghahremani, K., Texas Medicaid and CHIP in Perspective. 10th ed. (Feb. 2015); Gettings, Robert M., Forging a Federal-State Partnership: A History of Federal Developmental Disability Policy. AAIDD, NASDDDS (2011). | |||||||

Over the years, Congress also has authorized time-limited grant programs that have enabled states to increase beneficiary access to HCBS with enhanced federal matching funds and other features. These include the Real Choice Systems Change grants, the Money Follows the Person (MFP) demonstration, and the Balancing Incentive Program (BIP) (Table 2). Real Choice Systems Change grants were made available following the Olmstead decision to expand HCBS. MFP helps states transition beneficiaries from institutions to the community. From 2008 to mid-2015, over 52,000 beneficiaries nationally have moved from institutions to the community with the help of MFP enhanced federal matching funds.30 BIP has provided enhanced federal matching funds to 18 states that were spending less than half of their LTSS dollars on HCBS in 2009 to increase access to HCBS through structural reforms.31

| Table 2: Selected Grant Programs Aimed at Enhancing and Expanding Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services | |||||

| Grant Title | Years Authorized | Description | Funding Available | State Participation | |

| Real Choice Systems Change Grants | FY2001 – FY2010 | From 2001 through 2004, grants were intended to jump start new initiatives, supplement existing initiatives to increase their scope, and support states that had historically had less developed HCBS systems. Grants were typically directed at one or more aspects of a state’s HCBS system rather than promoting more comprehensive reform. Beginning in 2005, fewer grants were awarded, but the grant award amounts were larger, to promote more comprehensive systems change. | Between FY 2001 and FY 2010, CMS awarded 352 grants in 39 categories totaling approximately $288,586,710. | Grants were awarded in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. | |

| Money Follows the Person Demonstration | FY2007 – FY2016* | MFP provides states with enhanced federal Medicaid matching funds for 12 months for each beneficiary who transitions from an institution to the community, as well as administrative support and funding for services not otherwise covered. | $1.75 billion was appropriated for FY 2007-2011, and an additional $2.25 billion ($450 million for each FY 2012-2016) was appropriated when the program was extended. | In 2015, 43 states and the District of Columbia were participating in MFP. | |

| Balancing Incentive Program | FY2011 – FY2015 | BIP offers enhanced federal matching funds for Medicaid HCBS for states that spent less than half of their LTSS dollars on HCBS in FY2009. Participating states must implement 3 structural reforms (no wrong door/single entry point system, conflict-free case management, universal needs assessment). | $3 billion in enhanced Federal matching funds appropriated. | 21 states approved (13 continuing beyond Sept. 2015, through extension for use of existing funds). | |

| NOTE: *CY2016 is the last year states can request MFP funding, but states have until 2018 to use funds for institutional to community transitions and until 2020 to use funds to support participants in home and community-based settings post-transition. SOURCES: CMS, Real Choice System Change Grant Program, available at https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/long-term-services-and-supports/balancing/real-choice-systems-change-grant-program-rcsc/real-choice-systems-change-grant-program-rcsc.html; Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Money Follows the Person: A 2015 State Survey of Transitions, Services, and Costs (Oct. 2015), available at https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/money-follows-the-person-a-2015-state-survey-of-transitions-services-and-costs/; Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Medicaid Balancing Incentive Program: A Survey of Participating States (June 2015), available at https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-balancing-incentive-program-a-survey-of-participating-states/; Kaiser Family Foundation, State Health Facts, Balancing Incentive Program (Oct. 2015), available at https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/balancing-incentive-program/. | |||||

While states have reported success with both programs, BIP funding expired in 2015, and MFP funding is set to expire in 2016. Although states can continue to transition beneficiaries under MFP through 2018, and have until 2020 to use remaining program funds, states may be unable to continue their transition programs at current service levels and with existing staffing once federal funding expires.32 For example, MFP funds pre- and post-transition services that may not otherwise be available through Medicaid (such as security and utility deposits and other household set-up costs) as well as housing and outreach staff to help facilitate institutional to community moves. While states participating in BIP report that the program is helping to achieve their goal of rebalancing LTSS in favor of HCBS, by building on existing HCBS options and standardizing the infrastructure that facilities beneficiary access to HCBS, they also cited the relatively short implementation timeframe for the program as a challenge, given the significant structural reforms (no wrong door/single entry point system, core standardized assessment, conflict-free case management) required.33

In addition to the authorities described above, states have designed Section 11115 demonstrations that they believe may tip the balance of LTSS spending toward HCBS. For example, a sizeable number of states (17 in FY 2015, and 19 in FY 2016) report that they expect incentives built into their managed care programs to increase the availability of HCBS relative to institutional care.34 As of 2014, 12 states used Section 1115 demonstrations to provide LTSS through capitated managed care, with three states (AZ, RI, VT) now providing all home and community-based waiver services through Section 1115 instead of Section 1915(c).35 Other states are using Section 1115 authority to provide HCBS on a fee-for-service (FFS) basis. Minnesota has a Section 1115 demonstration that expands access to Section 1915(i) and CFC services as a means of preventing beneficiaries from requiring future institutional care,36 while Washington has a Section 1115 demonstration application pending with CMS that would expand HCBS while limiting access to nursing facility services.37

Key Policy Questions in Streamlining Medicaid HCBS

Policymakers have begun discussing streamlining Medicaid HCBS as a next step in expanding beneficiary access to community-based care. Continuing to improve access to HCBS is important as the demographics shift toward an aging population and medical and technological advances enable people with disabilities to live longer and more independently than ever before. Streamlining seeks to reduce the complexity experienced by states in administering and individuals and their families in navigating the array of programs that have emerged from a 35 year incremental approach to system design. Streamlining also would build on recent policy initiatives in other parts of the Medicaid program, such as the ACA’s enrollment simplification provisions and CMS’s final rule defining home and community-based settings across authorities for Medicaid funding purposes. Potential obstacles to streamlining include how to finance community-based services for eligible beneficiaries and how to manage program enrollment given state budgetary pressures. The rest of this brief discusses key policy questions raised by streamlining Medicaid HCBS and some of the challenges facing states, beneficiaries, and other stakeholders in implementing such an approach.

How Would Financial Eligibility for HCBS Be Determined?

Financial eligibility limits vary among the existing Medicaid HCBS authorities, and in some instances, people must have less income to qualify for HCBS than for institutional care. States choose which optional coverage groups to include in their programs and determine the income and asset limits for each group. The current variation in financial eligibility rules across HCBS authorities makes these programs complex for states to administer and beneficiaries to navigate. Additionally, if financial eligibility rules for HCBS are stricter than the rules to qualify for institutional care, people who can no longer live in the community without services may need to go into a nursing facility to receive services if HCBS are not available to them, even if they prefer to remain at home given a choice of setting. Once in an institution, returning to the community becomes more difficult as time passes, community-based housing is lost, and other community connections and supports are no longer maintained. While most states presently choose to use the same financial eligibility limit for Section 1915(c) HCBS waivers as for nursing facility and other institutional services, 25% of HCBS waiver programs in 2014 used more restrictive financial eligibility limits than the limit used for nursing facility services.38 A similar disincentive for HCBS can result if states implement Section 1915(i) HCBS or CFC attendant care services up to 150% FPL, while using higher financial eligibility rules to qualify for institutional care.

Streamlining Medicaid HCBS could address these challenges by aligning financial eligibility rules among the various HCBS eligibility pathways and between HCBS and institutional long-term care. For example, streamlining could consolidate some or all of the current eligibility pathways for accessing HCBS by establishing consistent income and asset rules. Streamlining also could consider how the HCBS rules align with financial eligibility for institutional care, to provide equitable access to both institutional and HCBS and avoid incentivizing institutional care over HCBS. Reducing or eliminating some of the variation in financial eligibility thresholds for different Medicaid HCBS pathways could create administrative efficiencies for states and make the program as a whole simpler for beneficiaries to navigate. With adequate financing, which is central to any streamlining initiative, financial eligibility rules could be aligned to accommodate the highest level at which current beneficiaries qualify for services instead of restricting current standards.

How Would States Manage Program Enrollment?

Today, states often use their ability to cap HCBS enrollment to control program costs, although this strategy also can have the effect of creating a bias toward institutional care. While the existing HCBS state plan authorities do not have enrollment caps, most HCBS are provided through Section 1915(c) waivers that do allow states to cap enrollment and expand as new resources become available. At the same time, all beneficiaries who qualify for Medicaid nursing facility services are entitled to receive them because enrollment for Medicaid state plan services cannot be capped. Because enrollment in HCBS waivers can be limited, everyone who needs LTSS may not be able to choose their preferred setting. If no HCBS waiver slots are open, a person who prefers to receive services at home but who can no longer live in the community without services may have to go into a nursing facility. Although such a person could potentially move from a nursing facility back to the community, this transition becomes more difficult as time passes and community housing and other supports are lost.

The ACA replaced the enrollment cap for Section 1915(i) state plan HCBS with enrollment management strategies that may offer a model for a streamlined Medicaid HCBS state plan option. Section 1915(i) allows states to offer HCBS to people whose functional needs do not yet rise to the level of institutional care, which could delay or avoid more costly future services. Section 1915(i) also permits states to control enrollment by constricting the functional eligibility criteria if the projected number of individuals expected to receive services is exceeded. Those already receiving services are grandfathered into the program under the old criteria when changes are made so that current beneficiaries do not lose services. In transitioning to a streamlined HCBS state plan authority, states would need time to ensure that the necessary infrastructure, including provider capacity to provide a range of HCBS, is in place. Additionally, adequate financing would have to be available to serve beneficiaries who are eligible for services without waiting lists. States’ experiences with managing program enrollment under Section 1915(i), in lieu of enrollment caps and waiting lists associated with Section 1915(c) waivers, can inform the design of a streamlined HCBS option as an alternative means of ensuring effective system development for each population served, while allowing for enrollment growth as certain milestones are achieved.

How Would Beneficiaries Functionally Qualify for Services?

At present, the contents of the HCBS benefit package available to an individual may vary depending on the underlying eligibility pathway or program authority. Because Section 1915(c) waivers can be targeted to specific populations and each may have their own distinct benefit package, all services may not be available to all beneficiaries who otherwise would qualify to receive them based on their functional needs. People with needs in more than one area may have to choose which services to forgo if all of their needs cannot be met through one of the existing targeted benefit packages. In addition, some services, like security and utility deposits and other household set-up costs, which help beneficiaries move from institutions to the community only may be available to certain populations under particular programs such as MFP or CFC, depending on state program design. Providing these transition services seeks to remedy the historical bias of the program toward institutional care by supporting beneficiaries who wish to move to the community to do so, an option that may not have been available to them when they were institutionalized. The ACA already has taken steps toward streamlining in this area by fully aligning the service options available under Section 1915(i) with those available under Section 1915(c) so that there is now a single set of HCBS from which states can choose regardless of whether they are using state plan or waiver HCBS authority.

Streamlining Medicaid HCBS could further consolidate the services available under existing authorities, allowing access to services based on an individual’s functional needs instead of tying eligibility to a particular program or authority. Streamlining also could consider whether to incorporate some of the services and supports that will expire when MFP funding sunsets that may not be available through other existing authorities. Offering a single set of HCBS to all beneficiaries does not mean that everyone would receive all of the services contained in the benefit package. Instead, beneficiaries still would need to satisfy medical necessity criteria and would receive only the services that meet their individual needs. Streamlining the existing HCBS benefit packages also would not alter the Medicaid program’s entitlement to institutional care for people with needs that cannot effectively be met in the community or whose situation requires an institutional setting.

How Would HCBS Be Incentivized?

Functional Eligibility Criteria

Functional eligibility rules to qualify for HCBS today can be more restrictive than for institutional services, creating a disincentive for HCBS, although states can expand access to HCBS to people with functional needs that are below an institutional level of care. As of 2014, 10 Section 1915(c) waivers in eight states (3% of all such waivers nationally) used stricter functional eligibility criteria to gain access to HCBS than what the state required to access institutional care.39 For example, a state could require an individual to have difficulty in performing at least three activities of daily living, such as bathing, dressing, transferring, eating, or toileting, for HCBS waiver eligibility but require limitations in only two of these areas for nursing facility admission. On the other hand, as noted above, Section 1915(i) enables states to offer state plan HCBS to people who need help with self-care and/or household activities although their needs do not rise to the level of institutional care. This standard is different from Section 1915(c) waiver services and CFC attendant care services, both of which require beneficiaries to qualify for institutional care. Section 1915(i) provides an opportunity to use HCBS as preventive care in an effort to foreclose or delay the need for more intensive costly services in the future if needs worsen without services.

A streamlined authority could incentivize HCBS by establishing functional eligibility criteria for at least some HCBS that are less stringent than what is required to qualify for institutional care. The test used for Section 1915(c) waivers – whether HCBS are less costly individually or in aggregate than comparable institutional care – could be used to determine whether a person’s needs cannot be met with appropriate HCBS in the community. In such cases, safeguards would be needed to ensure that beneficiaries receive the level of HCBS commensurate with their needs, particularly for those facing institutionalization. For example, if beneficiaries disagree with the amount or type of services authorized in their care plan, they can appeal that decision on the grounds that more or different services are medically necessary for their needs. Beneficiaries who prefer institutional care also could be permitted to choose that setting. While maintaining the availability of HCBS for people who need an institutional level of care is critical, this additional flexibility could enable states to provide HCBS as preventive services so that beneficiaries who want to do so can remain in their homes and avoid further decline in functioning and potentially higher costs in the future.

Enhanced Federal Matching Funds

The Medicaid program currently offers enhanced federal matching funds to states that choose to provide certain HCBS. For example, the CFC state plan option added by the ACA offers six percent enhanced federal matching funds for states to provide attendant care services and supports, provided that states meet certain criteria such as developing the benefit with stakeholder input, establishing a comprehensive quality assurance system, reporting information for a federal evaluation, and maintaining existing Medicaid attendant care spending in the first year. These federal financial incentives serve to remedy the historic bias toward institutional services and can be a tool in maintaining momentum toward expanding HCBS and further developing and maintaining the necessary system capacity.

Streamlining Medicaid HCBS could include enhanced federal financing to incentivize certain services. Enhanced federal funding for CFC services already exists in the law. Reauthorizing time-limited programs with enhanced federal funding, such as MFP, and/or creating new programs with enhanced federal funding would require sufficient funds to be available in federal and state budgets. Because HCBS are typically less expensive than comparable institutional care and can help prevent the need for more costly services in the future, programs may realize savings over time. Savings also may arise from efficiencies resulting from administering a single streamlined program. Depending on the availability of federal funds, offering an enhanced match for other targeted services may facilitate the expansion of key areas such as supported employment, self-direction, and other services aimed at increasing independence and community integration.

How Would the Program Be Administered, Monitored, and Evaluated?

The way in which Medicaid HCBS authorities currently are structured results in states using multiple authorities, often targeted to different populations, creating administrative complexity. For example, as of 2012, there are nearly 300 individual Section 1915(c) HCBS waivers in 47 states and DC. In addition to having to administer and oversee different reporting requirements associated with individual HCBS authorities, states also combine other Medicaid authorities, which come with distinct reporting requirements, with their HCBS programs. For example, states use various managed care authorities, with separate reporting requirements, to offer capitated managed LTSS programs. States also may offer Medicaid health homes to better integrate care for people with chronic conditions, and those populations may overlap with beneficiaries who use Medicaid LTSS, leading to another area to potentially align reporting requirements.40 While population-specific expertise can help inform program design, opportunities for administrative simplification could be beneficial.

Current Medicaid authorities vary widely in the number and type of quality measures, and new LTSS quality measures currently are being developed to fill in gaps. In addition to differences in existing measures among the various HCBS authorities, there is a general consensus that further development of LTSS quality measures is needed, particularly to assess health outcomes, quality of life and community integration.41 Today, Section 1915(c) HCBS waivers largely focus on administrative process requirements, rather assessments of outcomes such as an individual’s experience of care. The National Quality Forum presently is working to identify gaps in HCBS quality measurement.42 Further developments in oversight and quality measurement may result from CMS’s proposed rules that would require state Medicaid programs to implement a comprehensive written strategy for assessing and improving the quality of care and services provided to all Medicaid beneficiaries across all delivery systems including FFS and managed care.43

Streamlining Medicaid HCBS reporting requirements and quality measures could decrease administrative complexity for states and provide uniform information for beneficiaries and other stakeholders to compare. A streamlined HCBS authority could both align existing requirements and incorporate new measures as they are developed. Simplifying program administration for states could enable them to focus resources on providing services and improving beneficiary outcomes. A potential downside of streamlining in this area may mean that certain measures seen as important by some stakeholders are no longer tracked. On the other hand, including too many measures can prove to be unworkable, and streamlining may provide an opportunity to identify the most important and relevant measures to track and assess quality.

Looking Ahead

Medicaid HCBS play a central role for millions of people, many of whom need daily supports to meet a wide array of needs, but the current system can be complex for states to administer and confusing for individuals in need of services to navigate. Additionally, an institutional bias remains in the program structure because nursing facility services must be covered, while most HCBS are provided at state option. CMS has taken some steps toward streamlining requirements across HCBS authorities through its regulations that govern person-centered planning and define a “home and community-based setting” for Medicaid funding purposes.44 Building on these efforts by streamlining the existing Medicaid HCBS programs into a single state plan authority might alleviate some of the complexity and administrative costs associated with the program and support further progress in increasing beneficiary access to HCBS. Streamlining Medicaid HCBS also would be consistent with the ACA’s provisions that simplify and streamline Medicaid eligibility and enrollment for people who qualify in poverty-related coverage groups and seek to make these systems more accessible to consumers.45

Streamlining calls for identifying the most useful features of the existing HCBS options, determining how to promote the use of HCBS as less costly, less intensive interventions before the use of institutional services, and considering how best to enable states to meet beneficiary needs. Any changes to Medicaid HCBS programs would have to address how to ensure adequate financing, which is central to any streamlining effort, and how to manage program enrollment over time. At the same time, streamlining HCBS might save administrative costs for both CMS and the states, and a system that incentivizes HCBS could prove cost-effective in the long-term. Additionally, a streamlined system could increase beneficiary and families’ understanding of how to access services, although streamlining would have to address the vulnerability of the population that relies on these services to ensure that a transition to a new system is smooth.

Given the fragmentation of Medicaid HCBS to date, stakeholder input from various beneficiary populations will be important so that streamlining HCBS builds on existing eligibility pathways and services so that those currently receiving services do not lose them. Next steps in streamlining Medicaid HCBS authority may include engaging a variety of stakeholders, such as beneficiaries, states, community-based organizations, providers, and others; considering options to address potential concerns; and exploring financing mechanisms and the federal and state fiscal implications of a streamlined program.