The Status of Funding for Zika: The President’s Request, Congressional Proposals, & Final Funding

Zika virus, a mosquito-transmitted infection that until recently had caused little concern, has become an urgent global challenge with widespread transmission occurring in the Americas, a region that had previously not seen any cases before 2015. Predictions that local transmission would spread to the continental United States by summer were met with the first cases identified in Miami in July.1 Of particular concern is the discovery that Zika virus in pregnant women can cause microcephaly as well as other serious birth defects, prompting the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare a “public health emergency of international concern” on February 1st of this year.2

On the heels of the Ebola outbreak of 2014 – during which the U.S. government played a pivotal global role in the response including a request from the President and quick Congressional approval of more than $5 billion in emergency funds to combat Ebola3,4 – the President sought to launch a similar response to Zika. On February 22, the President sent a request to Congress for almost $1.9 billion in emergency Zika funding for Fiscal Year (FY) 2016, which would support domestic (including U.S. territories) and international response efforts including: mosquito control (vector management), expanded surveillance of transmission and infections, research and development activities (vaccines, diagnostics, and vector control methods), health workforce training, public education campaigns, and maternal and child health programs.5 Following the President’s request, Congress considered several Zika funding bills but did not approve any additional funding until the end of September. While Congress debated supplemental funding for Zika, the Administration announced it had identified almost $700 million in existing sources (largely from unobligated emergency Ebola funding appropriated in FY 2015) to be used to address immediate Zika activity needs.6,7,8 In September 2016, seven months after the President’s original request, Congress approved additional funding.

The Congressionally approved Zika funding, which was included as part of the “Continuing Appropriations and Military Construction, Veterans Affairs, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2017, and Zika Response and Preparedness Act” (P.L. 114-223), totals $1.1 billion.9 This brief compares approved funding levels to the President’s February 22nd request, the House and Senate bills that passed each chamber in May, and a Conference Agreement that had been approved by the House in June, but was blocked in the Senate and opposed by the Administration (see Table 1). 10,11,12,13

| Table 1: Timeline of Administration & Congressional Actions | |

| Proposal | Date of Most Recent Action |

| President’s Request | February 22, 2016 (Sent to Congress) |

| House (H.R. 5243) | May 18, 2016 (Passed by the House) |

| Senate (S. Amdt. 3900 to H.R. 2577) | May 19, 2016 (Passed by the Senate) |

| Conference Agreement (H.Rept. 114-640 to H.R. 2577) | June 23, 2016 (Passed by the House) |

| Final Funding (P.L. 114-223) | September 29, 2016 (Signed by the President) |

| SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of data from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), Agency Congressional Budget Justifications, Congressional appropriations bills and accompanying reports, and Congressional Research Service (CRS) reports. | |

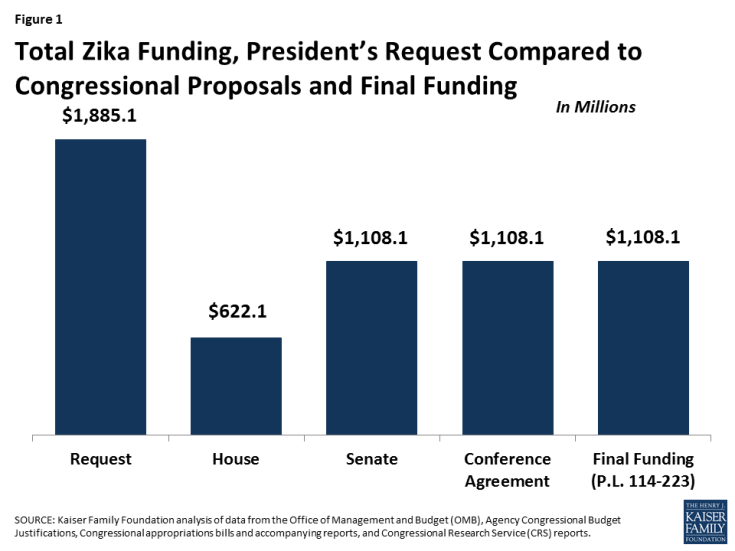

- Total Funding Amount: Each of the proposals and the final bill provide different levels of funding for the Zika response. The final bill provides $1.1 billion for Zika, significantly below the President’s Request of $1.89 billion, but equal to the Senate and Conference Agreement levels (see Figure 1 and Table 2). The final funding level is nearly double the House bill ($622.1 million).

| Table 2: Zika Funding (in millions) | |||||

| Agency / Department / Account | Request | House | Senate | Conference Agreement | Final Funding (P.L. 114-223) |

| State & Foreign Operations (SFOPs) | |||||

| Department of State | $41.1 (2%) |

$9.1 (1%) |

$37.1 (3%) |

$19.6 (2%) |

$19.6 (2%) |

| Diplomatic & Consular Programs | $14.6 (1%) |

$9.1 (1%) |

$14.6 (1%) |

$14.6 (1%) |

$14.6 (1%) |

|

International Organizations & Programs (IO&P) |

$13.5 (1%) |

– | $13.5 (1%) |

– | – |

|

Nonproliferation, Anti-terrorism, Demining, and Related Programs (NADR) |

$8.0 (<1%) |

– | $4.0 (<1%) |

– | – |

| Repatriation Loans | $1.0 (<1%) |

– | $1.0 (<1%) |

$1.0 (<1%) |

$1.0 (<1%) |

|

Emergencies in the Diplomatic and Consular Service (EDCS) |

$4.0 (<1%) |

– | $4.0 (<1%) |

$4.0 (<1%) |

$4.0 (<1%) |

| U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) | $335.0 (18%) |

$110.0 (18%) |

$221.0 (20%) |

$155.5 (14%) |

$155.5 (14%) |

| Global Health Programs (GHP) account | $325.0 (17%) |

$100.0 (16%) |

$211.0 (19%) |

$145.5 (13%) |

$145.5 (13%) |

| Operating Expenses | $10.0 (1%) |

$10.0 (2%) |

$10.0 (1%) |

$10.0 (1%) |

$10.0 (1%) |

| Total State & Foreign Operations (SFOPs): | $376.1 (20%) |

$119.1 (19%) |

$258.1 (23%) |

$175.1 (16%) |

$175.1 (16%) |

| Health & Human Services (HHS) | |||||

| Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) | $828.0 (44%) |

$170.0 (27%) |

$449.0 (41%) |

$476.0 (43%) |

$394.0 (36%) |

| Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services | $246.0 (13%) |

– | – | – | – |

| Food & Drug Administration (FDA) | $10.0 (1%) |

– | – | – | – |

| Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) | – | – | $51.0 (5%) |

– | – |

| National Institutes of Health (NIH) | $130.0 (7%) |

$230.0 (37%) |

$200.0 (18%) |

$230.0 (21%) |

$152.0 (14%) |

| Public Health & Social Services Emergency Fund (PHSSEF) | $295.0 (16%) |

$103.0 (17%) |

$150.0 (14%) |

$227.0 (20%) |

$387.0 (35%) |

| Total Health & Human Services (HHS): | $1,509.0 (80%) |

$503.0 (81%) |

$850.0 (77%) |

$933.0 (84%) |

$933.0 (84%) |

| Total Zika Funding: | $1,885.1 | $622.1 | $1,108.1 | $1,108.1 | $1,108.1 |

| SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of data from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), Agency Congressional Budget Justifications, Congressional appropriations bills and accompanying reports, and Congressional Research Service (CRS) reports. | |||||

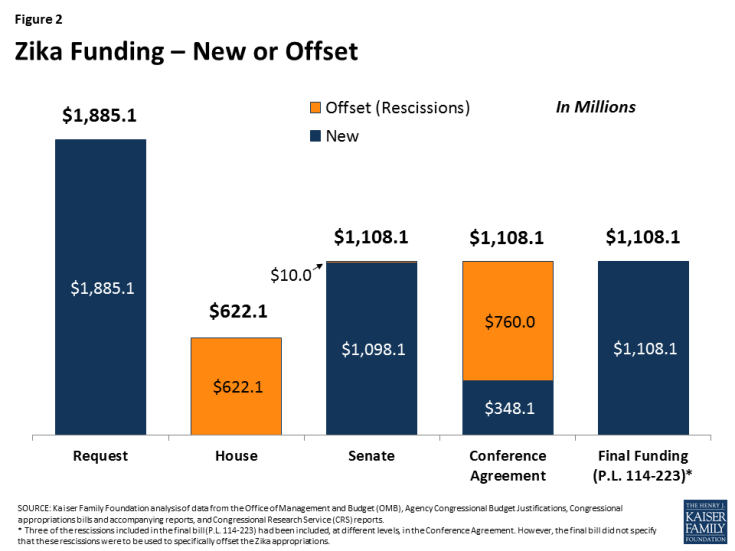

- New or Offset Funding: The President’s emergency request sought to obtain “new” appropriations for Zika (funding provided in addition to previous appropriations), rather than offset that funding from existing sources (e.g., through rescissions to prior appropriations). Each of the Congressional proposals and the final bill use a different approach with some requiring significant offsets to fund the Zika response (see Figure 2). For example, the House bill of $622.1 million would have been entirely offset through rescissions to previous congressionally approved appropriations ($352.1 million from unobligated emergency Ebola funding and $270 million from a non-recurring expenses fund at the Department of Health and Human Services). The majority of funding in the Senate bill would have been new with the exception of a $10 million rescission to unobligated emergency Ebola funding. Finally, the Conference Agreement would have been primarily funded through offsets (69%) through rescissions to emergency Ebola funding ($117 million), the non-recurring expenses fund ($100 million) at the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and the Affordable Care Act (ACA) ($543 million). The final bill, while including a number of rescissions, did not specify that these should be used to specifically offset Zika funding. If this is the case, the entire $1.1 billion would be new funding, although this remains to be seen.14

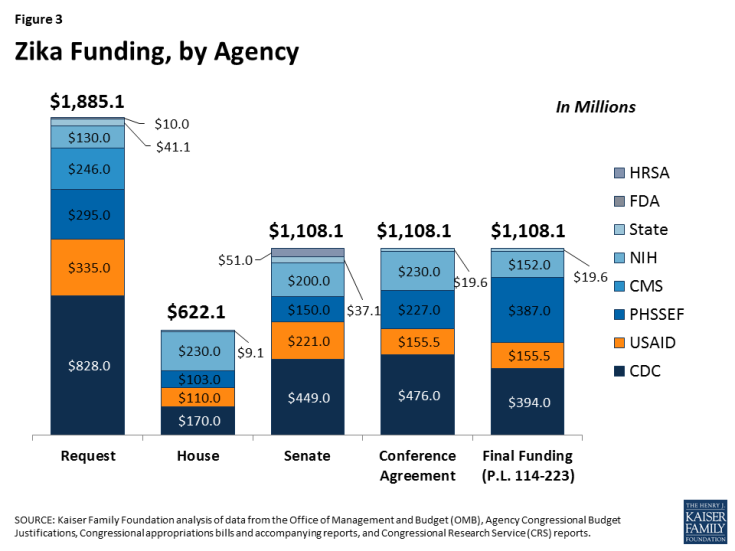

- Funding by Agency: Each of the Zika funding proposals and the final bill provide the majority of funding to HHS. The final bill provides more than 80% of funding to HHS, while the State Department and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) received the remaining funding (see Table 2). The final bill, the President’s request, and the original Congressional proposals, however, varied funding between agencies providing an indication of how each prioritized the U.S. response (see Figure 3). For instance, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) received the largest share of funding among all agencies (36%) in the final bill, similar to the President’s Request, Senate, and Conference Agreement, while the National Institutes of Health (NIH) accounted for the largest share of total funding (37%) in the House bill. The Public Health & Social Services Emergency Fund (PHSSEF) accounted for the second largest share (35%) in the final bill, whereas it would have received the third largest share in both the President’s Request (16%) and Conference Agreement (20%).

- Activities Supported: The President’s request included detailed information on the wide range of activities that would be funded both domestically and abroad through multiple agencies. These include: mosquito control (vector management) activities through CDC (both domestic and international) and USAID (international); research and development on vaccines, treatment, and diagnostics at NIH, CDC, FDA, and USAID; and support for maternal and child health activities through CDC (domestic only), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and USAID (international). While the Congressional proposals provide much less detail, there are several notable differences from the President’s request, starting with the amount of funding, as discussed above. In addition, there are some substantive differences, such as $246 million requested by the President to support maternal and child health activities by CMS in Puerto Rico and other U.S. territories, which is not included in any of the Congressional proposals, and varying policy provisions (e.g., concerning whether prior spending for Zika can be reimbursed) as described below.

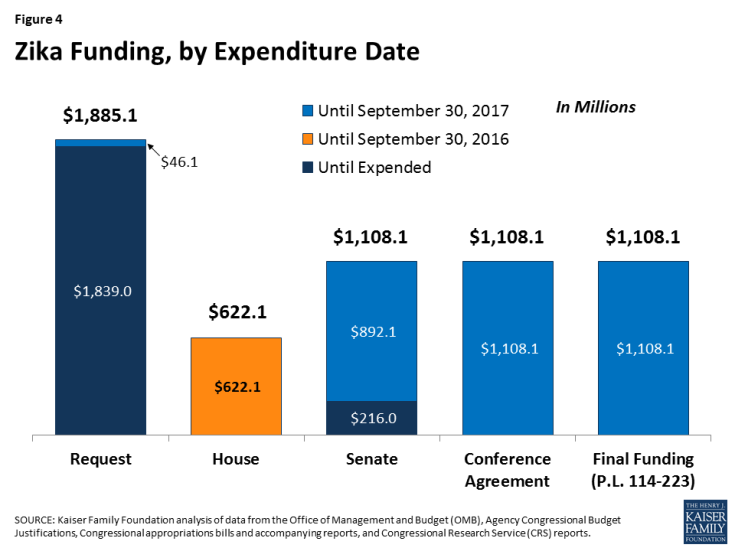

- Spending Period: Another difference between the proposals and final bill is the period of time for which funds would be available (see Figure 4 and Table 3). For instance, similar to the Conference Agreement, all of the funding in the final bill is available through FY 2017, whereas the majority of funding ($1.84 billion) in the President’s Request would have been available “until expended” meaning there would not have been a time limit on when the funds need to be spent. All funding in the House proposal would have been available only in FY 2016, the shortest period among all the proposals. The majority of the Senate proposal ($892 million) would have been available through FY 2017, with the remainder ($216 million; $211 million at USAID and $5 million at the State Department) available until expended.

| Table 3: Zika Funding – Spending Period | |||||

| Agency / Department / Account | Request | House | Senate | Conference Agreement | Final Funding (P.L. 114-223) |

| State & Foreign Operations (SFOPs) | |||||

| Department of State | – | Sep. 2016 | – | Sep. 2017 | Sep. 2017 |

| Diplomatic & Consular Programs | Sep. 2017 | – | Sep. 2017 | – | – |

|

International Organizations & Programs (IO&P) |

Sep. 2017 | – | Sep. 2017 | – | – |

|

Nonproliferation, Anti-terrorism, Demining, and Related Programs (NADR) |

Sep. 2017 | – | Sep. 2017 | – | – |

| Repatriation Loans | Until Expended | – | Until Expended | – | – |

|

Emergencies in the Diplomatic and Consular Service (EDCS) |

Until Expended | – | Until Expended | – | – |

| U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) | – | Sep. 2016 | – | Sep. 2017 | Sep. 2017 |

| Global Health Programs (GHP) account | Until Expended | – | Until Expended | – | – |

| Operating Expenses | Sep. 2017 | – | Sep. 2017 | – | – |

| Health & Human Services (HHS) | |||||

| Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) | Until Expended | Sep. 2016 | Sep. 2017 | Sep. 2017 | Sep. 2017 |

| Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services | Until Expended | – | – | – | – |

| Food & Drug Administration (FDA) | Until Expended | – | – | – | – |

| Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) | – | – | Sep. 2017 | – | – |

| National Institutes of Health (NIH) | Until Expended | Sep. 2016 | Sep. 2017 | Sep. 2017 | Sep. 2017 |

| Public Health & Social Services Emergency Fund (PHSSEF) | Until Expended | Sep. 2016 | Sep. 2017 | Sep. 2017 | Sep. 2017 |

| SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of data from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), Agency Congressional Budget Justifications, Congressional appropriations bills and accompanying reports, and Congressional Research Service (CRS) reports. | |||||

- Policy Provisions: Each of the Zika funding proposals and the final bill included policy provisions placing restrictions on how the funding would be utilized. For instance, the final bill, the President’s Request, the Senate, and the Conference Agreement include some authorities to reimburse prior obligations associated with the Zika response; the House proposal does not include reimbursement authority. The Conference Agreement would have placed a restriction on some of the funding directed to HHS that, it had been argued, would have prevented funds going to organizations that provide family planning and reproductive health services, and would have re-directed funds from other health efforts, including from the ACA, cited as some of the reasons why Democrats in the Senate blocked the bill. The final bill did not include these provisions.15