Private Contracts Between Doctors and Medicare Patients: Key Questions and Implications of Proposed Policy Changes

Today, when most people with Medicare see their doctors, they are generally responsible for paying Medicare’s standard coinsurance, but do not face additional or surprise out-of-pocket charges. This is a result of longstanding laws and regulations that were put into place to address unexpected and confusing charges that were previously more prevalent for Medicare patients. Under current law, physicians are paid under a fee schedule in Medicare, with limits on the amount they can balance bill beneficiaries per service, unless they choose to “opt out” of Medicare and “privately contract” with all of their Medicare patients. In recent years, some lawmakers have proposed to broaden the conditions under which doctors and other practitioners can privately contract with Medicare patients for the price of their services.

Legislation has been introduced in the House and Senate to make it easier for physicians and other practitioners to enter into private contracts with their Medicare patients and charge higher fees than are generally allowed under Medicare, including H.R. 1650 introduced by Representative Tom Price (now Health and Human Services Secretary nominee) and a companion bill, S. 1849, introduced by Senator Murkowski. Private contracting provisions are also included in broader bills to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA), such as H.R. 2300 introduced by Representative Tom Price and S. 1851 introduced by Senator McCain. Additionally, Speaker Paul Ryan and House Republicans proposed changes to private contracting through a demonstration project to be implemented by the Administration, as part of their plan, A Better Way.

Changes in Medicare’s private contracting laws could have significant implications for Medicare patients, doctors, and the Medicare program. Given recent interest in private contracting in Medicare, this brief:

- Summarizes the three options that physicians and practitioners currently have for charging Medicare patients for services they provide;

- Explains how the private contracting option works in Medicare under current law, including the patient protections, and the implications for beneficiaries’ out of pocket costs;

- Reviews current proposals on changes to private contracting in Medicare, and discusses the implications for Medicare patients, physicians, and the Medicare program.

Proposals to broaden private contracting in Medicare could create stronger financial incentives for physicians to see Medicare patients, but also expose a rising number of Medicare beneficiaries to unlimited physician charges—a key consideration for seniors and people with disabilities living on modest incomes.

Background: Current Provider Options for Charging Medicare Patients

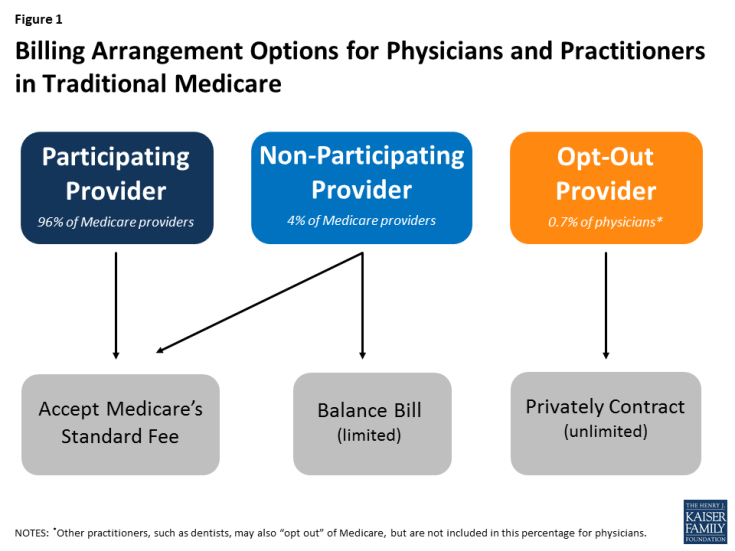

Under current law, physicians and practitioners have three options for charging their patients in traditional Medicare. They may register with Medicare as (1) a participating provider, (2) a non-participating provider, or (3) an opt-out provider who privately contracts with all of his or her Medicare patients for payment (Figure 1). These provider options have direct implications on the charges and out-of-pocket liabilities that beneficiaries face when they receive physician services.

- Participating providers agree to accept Medicare’s fee-schedule amount as payment-in-full for all Medicare covered services. When Medicare patients see participating physicians and practitioners, they are charged Medicare’s standard amounts and do not face higher out-of-pocket liability than the regular 20-percent coinsurance on most services. Participating providers may collect their applicable fees directly from Medicare. The vast majority (96%) of physicians and practitioners registered with Medicare are participating providers.

- Non-participating providers may choose—on a service-by-service basis—to charge Medicare patients higher fees than participating providers, up to a maximum limit—115 percent of a reduced fee-schedule amount. When doing so, Medicare patients are fully responsible for this added amount (balance billing) in addition to applicable coinsurance. When balance billing, non-participating providers bill their Medicare patients directly, rather than Medicare, for the full charge; their patient may then seek reimbursement from Medicare for its portion.1 A small share (4%) of physicians and practitioners registered with Medicare are non-participating providers.

- Opt-out providers with private contracts may charge their Medicare patients any fee they determine is appropriate for their services, as agreed upon in their contract.2 When doctors and Medicare patients enter into these private contracts, Medicare does not cover or reimburse the doctor or patient for any services provided by opt-out providers, which means that Medicare patients are responsible for the entire cost of any services they receive from them. An extremely small portion of physicians (less than 1% of physicians in clinical practice) have chosen to “opt-out” of Medicare for 2016 (Appendix Table 1). Psychiatrists comprise the greatest share of physicians who have opted out (almost 40 percent) and dental providers comprise the largest share among other types of practitioners. Doctors in concierge practice models (which typically charge an annual membership fee) are not required to opt-out of Medicare, but if they do not, they are subject to Medicare’s coverage and billing requirements.3

Effects of Private Contracting on Medicare Beneficiaries’ Out-of-Pocket Costs

Under current law, when a patient sees a physician who is a “participating provider” and accepts assignment, as most do, Medicare pays 80 percent of the fee schedule amount and the patient is responsible for the remaining 20 percent. For example, for a colonoscopy with biopsy, which is about $500 on Medicare’s fee schedule, Medicare pays $400 and the patient is responsible for the remaining $100. If the physician is a “non-participating provider,” he or she is permitted to balance bill Medicare patients up to a maximum of 115 percent of a reduced fee schedule amount. In this example, the beneficiary’s liability would rise to $166, rather than $100 (Appendix Table 2).

However, if a physician opts out of Medicare and privately contracts with his or her Medicare patients, the amount that physician may charge is not limited by Medicare; the patient is responsible for whatever the physician charges for a given service, as specified in their contract. If, in the example above, that physician charges the average out-of-network charge among private insurers, about $1,200, rather than $500, the patient is responsible for the full $1,200—a substantially higher amount than otherwise required.4 It is important to note, however, that this example is illustrative and there is no cap on the amount physicians can charge their patients under private contracts.

Current Patient Protections for Private Contracting in Medicare

The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (BBA) established a number of patient protections that doctors and practitioners must follow to be able to privately contract with Medicare patients. For example, prior to providing any service to Medicare patients, doctors must inform their Medicare patients in writing that they have “opted out” of Medicare and that Medicare will not reimburse for their services. Their Medicare patients must sign this document to signify their understanding and their right to seek care from a doctor or other practitioner who has not opted-out of Medicare. Also, doctors are prohibited from entering into private contracts with beneficiaries who are in the midst of experiencing an urgent or emergent health care event or who qualify for Medicaid benefits, generally due to very low incomes.5

Another statutory condition of current private contract arrangements requires doctors who have decided to opt out of Medicare to do so for all of their Medicare patients and for all of the services they provide to them; they cannot pick and choose which patients and which services apply. This requirement was intended to prevent confusion among patients as to whether or not each visit would be covered by Medicare and how much patients could expect to pay out-of-pocket, as well as address concerns about Medicare’s ability to protect beneficiaries from fraudulent billing. A two-year minimum time period for opting out was also established to ensure that beneficiaries can make knowledgeable choices when selecting their physicians, rather than be subject to frequent changes.6

How Would Recent Proposals Change Private Contracting in Medicare?

Members of Congress and physician organizations, such as the American Medical Association, have proposed eliminating certain conditions under which physicians and other providers are allowed to engage in private contracts with their Medicare patients. Introduced in several legislative bills, including ones to repeal the ACA, these proposals essentially seek two main changes in Medicare. First, they would allow physicians to contract more selectively, on a patient-by-patient and service-by-service basis, rather than be required to privately contract with all of their Medicare patients for all services. Second, they would allow Medicare patients and physicians to seek reimbursement from Medicare for an amount equal to what Medicare would normally pay for that service under the physician fee schedule.

Patients and physicians would also be eligible to seek some coverage for their expenses from supplemental insurance (such as individually purchased Medigap policies and employer-sponsored retiree coverage), under these private contracting proposals, but it is unclear whether these insurers would be required to pay such claims.7 Also, physicians would continue to not be able to private contract with beneficiaries who receive low-income assistance through Medicaid, it is unclear what the impact would be on these beneficiaries if other changes to the Medicaid program were also implemented.8

Also included in these private contracting proposals are specific provisions to preempt any state laws that limit the amount that doctors and other practitioners may charge their patients. Some states have put into place consumer protections that limit high charges from out-of-network providers through balance billing and unpredictable “surprise medical bills.”9 These problems have been more common in the commercial insurance market than in Medicare, due to the current program incentives for physicians to be “participating providers,” financial protections on balance billing, and low shares of doctors and other practitioners opting out of Medicare.

What Are the Implications of these Proposals for beneficiaries and physicians?

There are three major arguments put forward in support of these proposals. First, lifting restrictions on private contracting would provide a way for physicians to receive higher payments for the services they provide, compensating them for what some say are relatively low fees allowed by Medicare which, they say, have failed to keep pace with the rising costs of running their practices.10 This ability would offer greater autonomy to physicians and practitioners, which some say has been eroded though Medicare’s fee regulations and coverage rules, an issue physicians have raised with commercial insurers, as well.11

A second point often made in favor of these proposals is that they could potentially increase the overall number of doctors and other providers willing to accept Medicare patients because they could charge higher fees to some of their Medicare patients, without having to opt-out of Medicare and turn away all other Medicare patients. It is possible, for example, that some psychiatrists and oral surgeons—specialties with comparably high opt-out rates (Appendix Table 1)—could start taking more Medicare patients, if they are allowed to privately contract with some but not all others.

A third argument raised in support of these proposals is their potential to reduce beneficiary out-of-pocket costs because patients entering into private contracts would be able to seek reimbursement from Medicare for at least a portion of their doctor’s charges (or allow their doctors to collect this portion directly from Medicare), whereas under current law, Medicare is prohibited from reimbursing patients or doctors for services provided under private contract. Returning to the aforementioned example for a colonoscopy with biopsy, a beneficiary could pay less than $1,200 for the service if they seek and receive reimbursement from Medicare and/or Medigap, although the patient would still pay substantially more than if his or her physician accepted Medicare fees.

But a number of concerns have been raised about the potential implications of these proposals for beneficiaries and the Medicare program. For example, liberalizing private contracting rules in Medicare could lead to higher costs for more Medicare beneficiaries—a concern for many people who are living on limited incomes and modest savings. Today, half of all people on Medicare live on incomes of about $24,000 or less.12 If substantially greater numbers of physicians and practitioners begin to privately contract with their Medicare patients for higher fees, then more beneficiaries could be exposed to higher costs for more of the services they receive. Under these proposals, there would continue to be no limit to the amount a doctor could charge a patient for a Medicare-covered service, if that patient agrees to the charges in the private contract with that physician.

Additionally, there is the concern that with the expansion of private contracting, some beneficiaries could lose access to affordable services, rather than gain it, particularly for less common physician specialties, such as oncology or certain surgical specialties, and in certain areas of the country, including rural communities, where patients may already have relatively few doctors available. In these cases, Medicare patients may feel that they have no choice but to agree to the terms of physicians’ contracts, even if the higher fees are unaffordable. This could be an issue for patients looking for new doctors as well as for patients wanting to keep their current doctors. Along those lines, a potential risk arises for patients in having doctors and other practitioners make a judgment as to which of their Medicare patients can afford higher (privately contracted) fees, and by how much. While proponents suggest that doctors have a sense of their patients’ ability to pay higher fees, and will privately contract only with their higher income patients, critics have noted concern that physicians are not well positioned to assess their patients’ financial situation, putting their patients in a difficult position of having to disclose their finances or discontinue care with that doctor.

What Are the Potential Effects of these Proposals on Medicare Spending?

The Congressional Budget Office has not estimated the effects of these proposals on Medicare spending, but more extensive private contracting in Medicare could potentially increase Medicare spending in a couple of ways. For instance, Medicare does not currently cover any services that are provided under private contract, so proposals that allow Medicare beneficiaries or their doctors to seek reimbursement for any portion of such services would increase Medicare spending. In addition, Medicare spending could rise if “non-participating” providers decide to switch to private contracting with their Medicare patients, rather than be subject to Medicare’s balance billing limits. This is because Medicare reimbursements for services provided under a private contract would be based on the standard fee schedule rate, which is about 5-percent higher than the rate for non-participating providers.

Discussion

As the 115th Congress gets underway, policymakers may consider proposals to ease private contracting rules under Medicare for physicians. Proponents say such proposals would increase physician autonomy, and create stronger financial incentives for physicians to treat Medicare patients by allowing them to charge higher fees to at least some of them. Additionally, these proposals could provide some financial relief to Medicare patients who enter into private contracts with their physicians, by allowing Medicare to cover a portion of the costs for services provided under these private contracts.

However, opponents caution that efforts to ease private contracting rules could lead to an unraveling of the financial protections that have been in place under Medicare for many years, and subject a growing number of beneficiaries to potentially unexpected and unaffordable charges. Further, such proposals could make it more difficult for some patients to keep their doctors, or find others with affordable fees—a particular issue for people on Medicare with modest incomes and significant health care needs. Additionally, critics of these proposals caution that beneficiaries living in areas with a limited choice of physicians might find it harder to find a doctor who accepts Medicare’s standard fees if a growing number of providers in their areas choose to require private contracts with their Medicare patients. And, if these proposals result in a growing number of doctors choosing to privately contract with their patients, they could result in an increase in Medicare spending which would have an impact on the federal budget and beneficiary premiums.

The key issue for Medicare and policymakers is to strike a balance between assuring that doctors and practitioners receive fair payments from Medicare while also preserving financial protections and incentives that help beneficiaries face predictable and affordable costs when they seek medical care.

This issue brief was funded in part by The Retirement Research Foundation.