States Respond to COVID-19 Challenges but Also Take Advantage of New Opportunities to Address Long-Standing Issues: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2021 and 2022

The coronavirus pandemic has generated both a public health crisis and an economic crisis, with major implications for Medicaid—a countercyclical program—and its beneficiaries. The pandemic has profoundly affected Medicaid program spending, enrollment, and policy, challenging state Medicaid agencies, providers, and enrollees in a variety of ways.1 As states continue to respond to pandemic challenges, they are also pushing forward non-emergency initiatives as well as preparing for the unwinding of the public health emergency (PHE) and the return to a new normal of operations. The current PHE declaration expires on January 16, 2022,2 though the Biden Administration could renew the declaration again and has notified states that it will provide 60 days of notice prior to the declaration’s termination or expiration.3 The duration of the PHE will affect a range of emergency policy options4 in place as well as a 6.2 percentage point increase in the federal match rate (“FMAP”)5 (retroactive to January 1, 2020) available if states meet certain “maintenance of eligibility”6 requirements included in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA).7

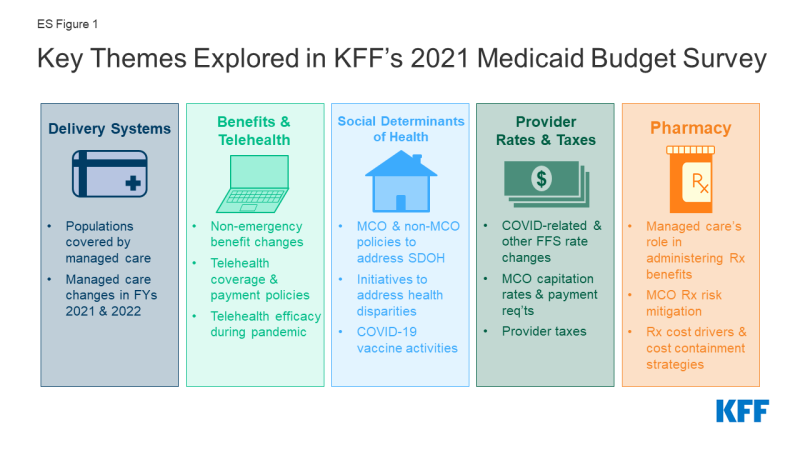

This report highlights certain policies in place in state Medicaid programs in state fiscal year (FY) 2021 and policy changes implemented or planned for FY 2022, which began on July 1, 2021 for most states;8 we also highlight state experiences with policies adopted in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings are drawn from the 21st annual budget survey of Medicaid officials in all 50 states and the District of Columbia conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) and Health Management Associates (HMA), in collaboration with the National Association of Medicaid Directors (NAMD). States completed this survey in mid-summer of 2021, following increased vaccination rates and declining COVID-19 cases but just prior to a new wave of COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations, and deaths driven by the highly contagious Delta variant. Overall, 47 states responded to this year’s survey, although response rates for specific questions varied.9 This report summarizes key findings across five sections: delivery systems, benefits and telehealth, social determinants of health (which also includes information on health equity and COVID-19 vaccine uptake), provider rates and taxes, and pharmacy (ES Figure 1).

Delivery Systems

The vast majority of states that contract with managed care organizations (MCOs) reported that 75% or more of their Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in MCOs as of July 1, 2021.10 Children and adults (particularly expansion adults) are much more likely to be enrolled in an MCO than elderly or individuals with disabilities. MCOs provide comprehensive acute care (i.e., most physician and hospital services) and in some cases long-term services and supports (LTSS) to Medicaid beneficiaries. MCOs are at financial risk for the services covered under their contracts and receive a per member per month “capitation” payment for these services.11 Enrollment in Medicaid MCOs has grown12 since the start of the pandemic, tracking with overall growth in Medicaid enrollment.13 Throughout other sections of this survey, we report state policy changes that often apply to both the managed care and/or fee-for-service (FFS) delivery systems.

Benefits and Telehealth

The number of states reporting new benefits and benefit enhancements in FY 2021 and FY 2022 greatly outpaced the number of states reporting benefit cuts and limitations. While state benefit actions are often influenced by prevailing economic conditions,14 when the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting economic downturn hit, instead of restricting benefits, most states used Medicaid emergency authorities to temporarily adopt new benefits, adjust existing benefits, and/or waive prior authorization requirements.15 States may choose to permanently extend these emergency benefit changes past the PHE period. Many states are now focused on expanding behavioral health services, care for pregnant and postpartum women, dental benefits, and housing-related supports.

An overwhelming majority of states noted the benefits of telehealth in maintaining or expanding access to care during the pandemic, particularly for behavioral health services. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, many states expanded Medicaid telehealth coverage, including through the use of Medicaid emergency authorities.16 Preliminary CMS data shows that utilization of telehealth in Medicaid and CHIP has dramatically increased during the pandemic; however, telehealth access is not equally available to all Medicaid enrollees.17 Nearly all responding states report covering a range of services via audio-visual telehealth as of July 2021, with slightly fewer states reporting audio-only coverage. All or nearly all responding states at least sometimes cover audio-visual delivery of behavioral health, reproductive health, and well/sick child services, with fewer states reporting audio-visual coverage of HCBS and dental services. Trends in telehealth utilization during the pandemic vary across states. Post-pandemic telehealth coverage and reimbursement policies are being evaluated in most states, with states weighing expanded access against quality concerns, especially for audio-only telehealth.

Social determinants of health

Most states reported that the COVID-19 pandemic prompted them to expand Medicaid programs to address social determinants of health, especially related to housing. States also report existing initiatives in this area in MCO contracts (e.g., requirements for MCOs to screen and refer enrollees for social needs). Social determinants of health (SDOH) are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age that shape health.18 In response to the pandemic, federal legislation has been enacted to provide significant new funding to address the health and economic effects of the pandemic including direct support to address food and housing insecurity as well as stimulus payments to individuals, federal unemployment insurance payments, and expanded child tax credit payments. While measures like these have a direct impact in helping to address SDOH, health programs like Medicaid can also play a supporting role. Although federal Medicaid rules prohibit expenditures for most non-medical services, state Medicaid programs have been developing strategies to identify and address enrollee social needs both within and outside of managed care.

Three-quarters of responding states reported initiatives to address disparities in health care by race/ethnicity in Medicaid, with many focusing on specific health outcomes including maternal and infant health, behavioral health, and COVID-19 outcomes and vaccination rates. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated already existing health disparities for a broad range of populations, but specifically for people of color.19 Multiple analyses of available federal, state, and local data show that people of color are experiencing a disproportionate burden of COVID-19 cases and deaths. In addition to worse health outcomes, data from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey show that during the pandemic, Black and Hispanic adults have fared worse than White adults across nearly all measures of economic and food security.20

States report a variety of MCO activities aimed at promoting the take-up of COVID-19 vaccinations. These include member and provider incentives, member outreach and education, provider engagement, assistance with vaccination scheduling and transportation coordination, and partnerships with state and local organizations. Given the large number of people covered by Medicaid, including groups disproportionately at risk of contracting COVID-19 as well as many individuals facing access challenges, state Medicaid programs and Medicaid MCOs (which enroll over two-thirds of all Medicaid beneficiaries)21 can be important partners in COVID-19 vaccination efforts.22

Provider Rates and Taxes

Reported FFS rate increases outnumber rate restrictions in both FY 2021 and FY 2022, with more than two-thirds of states indicating payment changes related to COVID-19. The most common COVID-19-related payment changes were rate increases for nursing facilities and home and community-based services (HCBS) providers. Although states historically are more likely to restrict rates during economic downturns, states likely found rate reductions to be less feasible as many providers faced financial strain from the increased costs of COVID-19 testing and treatment or from declining utilization of non-urgent care, especially in the early months of the pandemic.23 Starting early in the pandemic, Congress, states,24 and the Administration adopted a number of policies to ease financial pressure on hospitals and other health care providers.25

Among states that implemented COVID-19-related risk corridors in 2020 or 2021 MCO contracts, about half reported that they have or will recoup funds, while recoupment in the remaining states remains undetermined. Although state capitation payments to MCOs (and prepaid health plans, known as PHPs) must be actuarially sound,26 states use a variety of mechanisms (including risk corridors) to adjust managed care plan risk, incentivize performance, and ensure plan payments are not too high or too low.27 While most states rely on capitated arrangements with comprehensive MCOs to deliver Medicaid services to most of their Medicaid populations, state-determined FFS rates remain important benchmarks for MCO payments in many states, often serving as the state-mandated payment floor. About two-thirds of responding states with managed care plans (MCOs or PHPs) reported minimum fee schedule requirements that set a reimbursement floor for one or more specified provider types.

Pharmacy

A majority of responding states reported prohibiting spread pricing in MCO subcontracts with their pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), which reflects a significant increase in state Medicaid agency oversight of MCO subcontracts with PBMs compared to previous surveys. The administration of the Medicaid pharmacy benefit has evolved over time to include delivery of these benefits through MCOs and increased reliance on PBMs.28 PBMs may perform a variety of administrative and clinical services for Medicaid programs (e.g., negotiating rebates with drug manufacturers, adjudicating claims, monitoring utilization, overseeing preferred drug lists (PDLs) etc.) and are used in FFS and managed care settings. MCO subcontracts with PBMs are under increasing scrutiny as more states recognize a need for transparency and stringent oversight of these subcontract arrangements.

More than half of states reported newly implementing or expanding at least one initiative to contain prescription drug costs in FY 2021 and/or FY 2022. While Medicaid net spending on prescription drugs remained almost unchanged from 2015 to 2019, spending before rebates increased, likely reflecting the launch of expensive new brand drugs and increasing list prices.29 As a result, state policymakers remain concerned about Medicaid prescription drug spending growth and the entry of new high-cost drugs to the market. States continuously innovate to address these pressures with cost containment strategies and utilization controls that include but are not limited to PDLs, managed care pharmacy carve-outs, and multi-state purchasing pools. A number of states also report laying the groundwork to employ value-based arrangements (VBA) with pharmaceutical manufacturers as a way to control pharmacy costs.

Looking ahead

States completed this survey in mid-summer of 2021, following increased vaccination rates and declining COVID-19 cases but just prior to a new wave of COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations, and deaths driven by the highly contagious Delta variant. At that time, states continued to focus on ongoing pandemic-related challenges for agencies, providers, and enrollees, but were also looking ahead to prepare for challenges associated with the unwinding of the PHE. Despite the upheaval caused by the pandemic, states also continued to advance non-emergency priority initiatives and to maintain efficient and effective program operations.

State officials also pointed to lessons learned during the pandemic that may provide opportunities to strengthen relationships with providers, develop new relationships with other community stakeholders, and improve enrollee access and outcomes during and beyond the PHE transition period. States identified ongoing efforts to advance delivery system reforms and to address health disparities and social determinants of health as areas of promise to build on in the future. Looking ahead, uncertainty remains regarding the future course of the pandemic and what kind of “new normal” states can expect in terms of service provision and demand as well as challenges associated with the unwinding of the PHE. In addition, as part of budget reconciliation, Congress is currently considering additional Medicaid policies building on earlier legislation to expand coverage and increase HCBS funding, which could have further implications for the direction of Medicaid policy in the years ahead. Finally, states may pursue and CMS under the Biden administration may promote Section 1115 demonstration waivers to help improve social determinants of health and advance health equity.30

Acknowledgements

Pulling together this report is a substantial effort, and the final product represents contributions from many people. The combined analytic team from KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA) would like to thank the state Medicaid directors and staff who participated in this effort. In a time of limited resources and challenging workloads, we truly appreciate the time and effort provided by these dedicated public servants to complete the survey and respond to our follow-up questions. Their work made this report possible. We also thank the leadership and staff at the National Association of Medicaid Directors (NAMD) for their collaboration on this survey. We offer special thanks to Jim McEvoy and Kraig Gazley at HMA who developed and managed the survey database and whose work is invaluable to us; and to Meghana Ammula at KFF who assisted with review of data and text.