Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost Sharing Policies as of January 2018: Findings from a 50-State Survey

Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment and Renewal Processes

In addition to expanding Medicaid to reach many previously ineligible low-income adults, the ACA established streamlined, modernized enrollment and renewal processes for low-income children and adults across all states (Box 1). The policies and practices standardized by the ACA drew on previous innovations some states pursued that proved effective and efficient for enrolling and retaining eligible children in coverage. Many states needed to make major upgrades to or replace antiquated eligibility systems to implement these new processes. The federal government supported the development of these systems by providing 90% federal match for their development and by only requiring non-health programs to pay the incremental add-on costs to be integrated into the updated Medicaid eligibility systems.

| Box 1: Key Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment and Renewal Policies Established Under the ACA |

|

Since the ACA was enacted, states have invested significant time and resources to upgrade or build new eligibility systems and re-engineer their business processes. As outlined in the findings below, with these efforts, the Medicaid enrollment and renewal experience has moved from a paper-based, manual process that could take days and weeks in some states to a modernized, technology-driven approach that can happen in real-time through electronic data matches to verify eligibility criteria. States use these same methods to automate the renewals without requiring enrollees to complete forms or submit paperwork when they can verify information through electronic data matches. Five years into implementation, leading states are now using automated processes to verify and renew eligibility for a majority of applicants and enrollees.

In 2017, states continued to advance enrollment and renewal processes but also focused attention and resources on other priorities. Some states continued to implement simplifications and enhancements to their processes and systems. Several additional states implemented real-time determinations or automated renewals and a few states reintegrated eligibility determinations for seniors and people with disabilities and non-health programs into their upgraded systems. Many other changes were incremental, such as expanding features of online applications and accounts and increasing the share of applications that receive real-time determinations. This leveling off of continued advancement in part reflects that states have largely achieved improved processes now that they are five years into implementation. However, other policy proposals over the past year, including proposals to repeal the ACA, change the financing and structure of Medicaid, and an extended gap in federal funding for CHIP, may have shifted attention away from the focus on improvements to enrollment and renewal processes.

Applications, Online Accounts, and Mobile Access

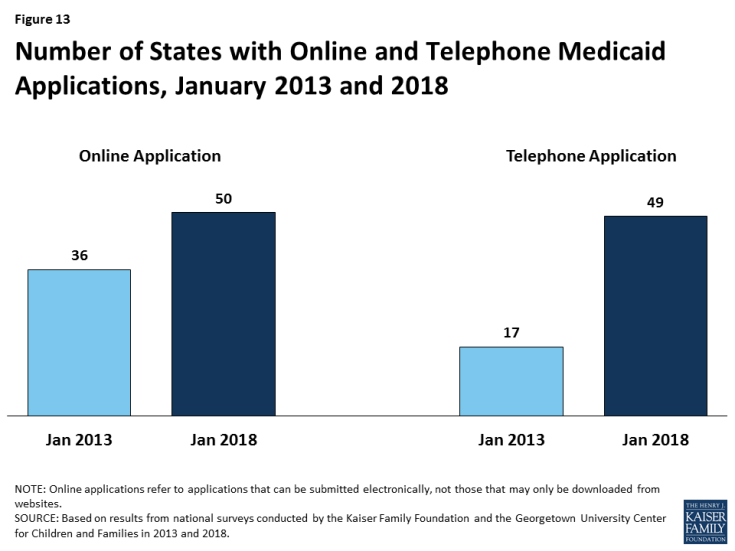

Individuals can apply for Medicaid online and by phone in nearly all states as of January 2018. To facilitate access to coverage, under the ACA, states must provide multiple application methods for individuals, including online, by phone, by mail, and in person. Prior to the ACA, some states had made progress offering online applications for Medicaid, but only 36 states had online applications that could be completed using an electronic signature, and less than a third of states (17) allowed applicants to apply over the phone (Figure 13). As of January 2018, Tennessee is the only state without an electronic application and telephone applications are available in 49 states.

In some states, online applications have become the predominant mode of application for individuals, but use of the online application varies across states and other application modes remain important. At least 50% of Medicaid applications are submitted online in 20 of the 39 states that were able to report the share of applications received online. However, in other states, online applications account for just a small share of applications. Telephone applications represent a smaller share of applications, less than 25% in most of the states able to report these data. As such, other application modes, including in person and mail, remain important, particularly for individuals who lack access to high speed internet or who feel more comfortable applying in-person.

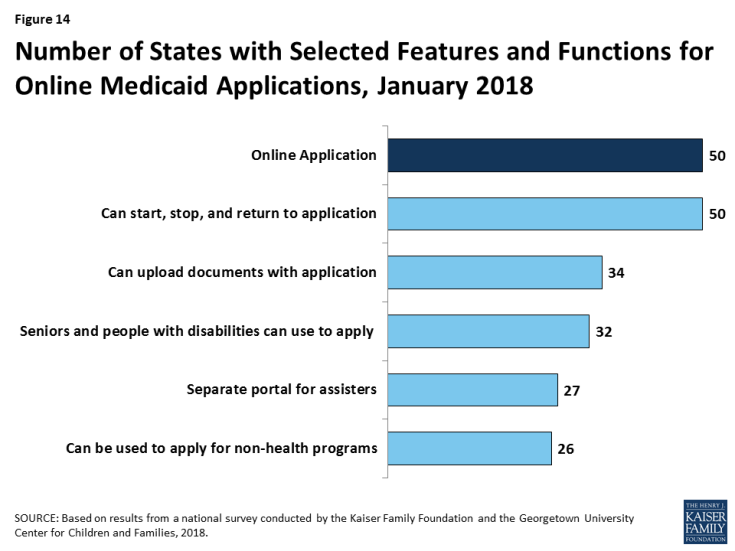

States have expanded consumer friendly features of online applications over time. In all 50 states with an online application, applicants can start, stop, and return to finish the application at a later time (Figure 14). In addition, states have increasingly added the ability for individuals to upload electronic copies of documentation with their application if needed. Between 2013 and 2018, the number of states with this functionality grew from 15 to 34, including Utah, which added this option in 2017.

Figure 14: Number of States with Selected Features and Functions for Online Medicaid Applications, January 2018

The number of states offering a multi-benefit online application is growing, but individuals still must complete separate applications for Medicaid and non-health programs in about half of states. As of January 2018, 32 states offer an online application for all Medicaid groups, including seniors and people with disabilities. Individuals can also apply for a non-health program, such as SNAP or TANF, using the online application in more than half of the states. These counts include Ohio, which added a multi-benefit application that incorporates SNAP and TANF, and New Jersey, which added seniors and individuals with disabilities to its Medicaid application for low-income children and adults during 2017.

Just over half of the states (27) have a web portal or secure login that enables consumer assisters to submit applications on behalf of consumers they help. In 2017, Utah added a portal for consumer assisters. This functionality helps states track, monitor, and report the work of assisters. In some states, these portals have additional functions or features that support the work of assisters, such as the ability to check a renewal date. Providing assisters with more tools may help reduce workloads on state administrative staff, for example, if assisters are able to update addresses and other information.

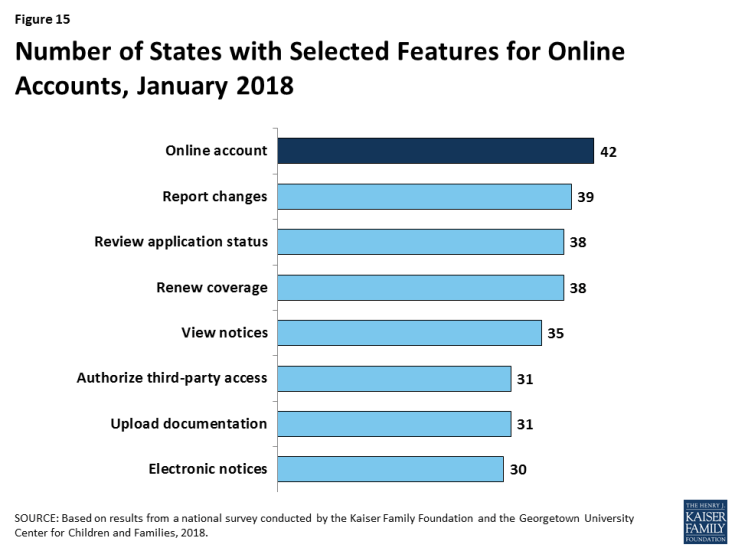

Many states provide online accounts for enrollees to manage their Medicaid coverage, and states have expanded the features and functions of these accounts over time. Online accounts create administrative efficiencies by reducing mailing costs, call volume, and manual processing of updates such as an address change. They also provide enrollees increased autonomy to manage and monitor their coverage. Between 2013 and 2018, the number of states providing online accounts grew from 36 to 42. As of January 2018, these online accounts offer a wide array of functions (Figure 15). Although many states have made online accounts available to enrollees, it is unclear what share of enrollees use these accounts on a regular basis.

In more than half of states, individuals can access online applications and accounts through mobile devices, but many of the applications and accounts do not have mobile-friendly formatting. As of January 2018, individuals in 31 states can complete and submit the online Medicaid application through a mobile device. Eleven of these states have designed a mobile-friendly version of the application and/or developed a mobile “app” for individuals to apply through a mobile device. Similarly, in 30 of the 42 states with online accounts, enrollees can access their account through a mobile device. In 14 of these states there is a mobile-friendly version of the account and/or the state has created an “app.” A number of states indicate that they plan to enhance mobile access to online applications and accounts in the future.

Eligibility Determinations and System Integration

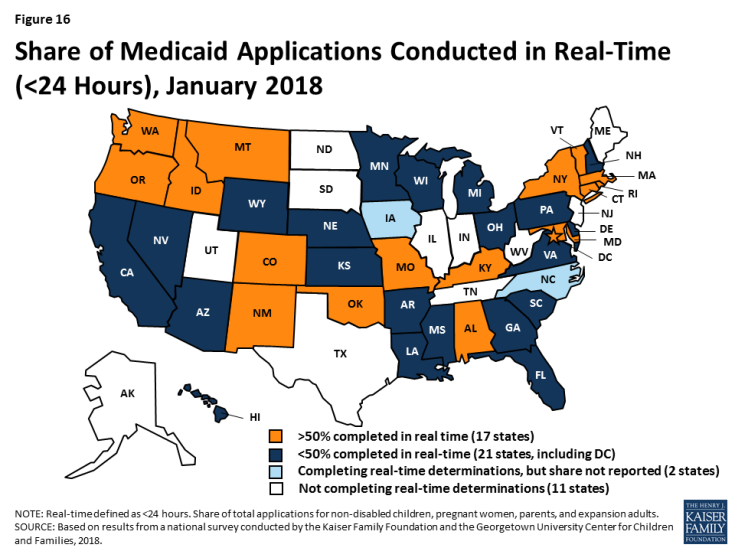

As of January 2018, 40 states are able to make real-time Medicaid eligibility determinations (defined as within 24 hours). This count reflects the addition of Georgia, which began determining eligibility in real-time in 2017. Prior to the ACA, states could verify some information electronically, like Social Security information or dates of birth, but for other aspects of eligibility, particularly income, eligibility workers often had to review paper documents like pay stubs or manually look up information in other data sources. This process often resulted in backlogs of applications, follow-up requests for information, and delays associated with matching up applications with verification documents. Today’s upgraded eligibility systems are able to check against other electronic data sources in real-time or overnight, providing timely eligibility decisions and reducing burdens for both individuals and staff. As state systems and processes have matured, they are able to process an increasing share of applications in real time. As of January 2018, at least 50% of applications receive a real-time determination in 17 of the 38 states that complete real-time determinations and were able to report this data (Figure 16), up from 15 in 2017. This count includes 11 states that report over 75% of applications receive a real-time decision, up from nine states in 2017.

When making Medicaid and CHIP eligibility determinations, all states verify citizenship or qualified immigration status of applicants, as well as income. States must verify citizenship or qualified immigration status for individuals prior to enrollment, although individuals who attest to a qualified status must be given a reasonable amount of time to provide documentation if eligibility cannot be confirmed electronically. States also must verify income. Nearly all states (44 states) verify income prior to enrollment, while seven states complete the verification after enrollment. Verification policies for other eligibility criteria, such as age/date of birth, state residency, and household size, vary across states, reflecting state options to confirm this information before or after enrollment or to accept self-attestation of information. If a state has any data that conflicts with the self-attestation, it must validate the information.

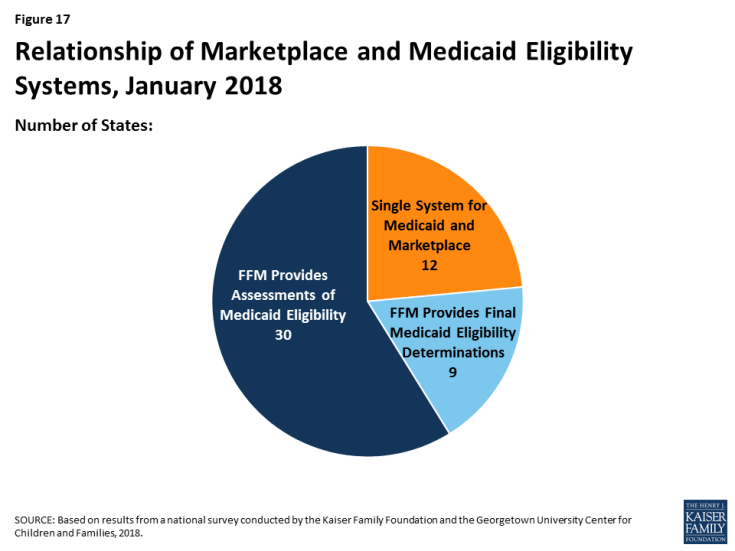

Reflecting ACA provisions for states to coordinate coverage across insurance affordability programs, all states have their Medicaid eligibility system integrated with or connected to CHIP and Marketplace systems. Prior to the ACA, half of states with separate CHIP programs (16 of 38) had separate eligibility systems for Medicaid and CHIP. As of January 2018, nearly all (34 of the 36) states with a separate CHIP program use a single system for Medicaid and CHIP. States’ integration and coordination with Marketplace systems varies reflecting differences in Marketplace structure (Figure 17). Most states with State-based Marketplaces (SBMs) (12 of 17) use the same system for Medicaid and Marketplace coverage. The other five SBM states rely on the Federally-Facilitated Marketplace’s (FFM’s) technology platform (Healthcare.gov) for Marketplace coverage, as do the remaining 34 FFM states. States using Healthcare.gov must electronically transfer data with the FFM to coordinate Medicaid and Marketplace coverage. Nine of these states have authorized the FFM to make final Medicaid eligibility determinations and enroll individuals in Medicaid immediately after receiving data from the FFM. In the other 30 states, the FFM preliminarily assesses Medicaid or CHIP eligibility and then the state may check state data sources or request additional documentation before completing the eligibility determination. When the ACA was first implemented, there were significant problems with account transfers that contributed to delays in Medicaid or CHIP enrollment. As of January 2018, only two states report ongoing, regular delays or difficulties with transfers.

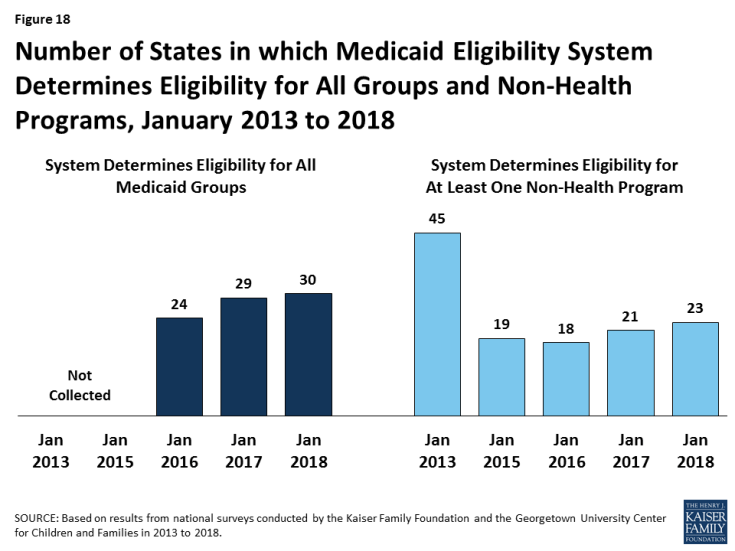

States are reintegrating Medicaid eligibility determinations for seniors and people with disabilities and non-health programs into their upgraded systems, but Medicaid eligibility remains separate from non-health programs in more than half of states, limiting the ability to coordinate services across programs. Given the complexity and resources associated with updating eligibility systems and processes, when states first implemented new systems and policies, many focused on groups directly affected by the ACA changes, including children, pregnant women, parents, and expansion adults. As such, when states rolled out new systems, most continued to process determinations for seniors and people with disabilities and non-health programs through their old systems. Therefore, Medicaid eligibility determinations were separated from non-health programs in many states. As new systems have matured, a growing number of states have reintegrated determinations for individuals with disabilities and seniors and non-health programs into their upgraded systems (Figure 18). As of January 2018, 30 states use one system to determine eligibility for all Medicaid groups, including New Jersey, which integrated seniors and people with disabilities into its system in 2017. In 23 states, the Medicaid system includes at least one non-health program, including Kansas and Ohio, which added some non-health programs in 2017. However, in more than half of states, Medicaid eligibility remains separate from non-health programs, limiting the ability to coordinate services for individuals across programs.

Figure 18: Number of States in which Medicaid Eligibility System Determines Eligibility for All Groups and Non-Health Programs, January 2013 to 2018

Some states have taken up the option to provide presumptive eligibility, which can help facilitate access to coverage for individuals who cannot have their eligibility verified in real-time. Presumptive eligibility is a longstanding option in Medicaid and CHIP that allows states to authorize qualified entities—such as community health centers or schools—to make a temporary eligibility determination to expedite access to care for children and pregnant women while the full application is processed. The ACA broadened the use of presumptive eligibility in two ways. First, it allowed states that provide presumptive eligibility for children or pregnant women to extend the option to parents, adults, or other groups. Second, the ACA gave hospitals nationwide the authority to determine eligibility presumptively for all non-disabled individuals under age 65. Use of presumptive eligibility for children and pregnant women has remained largely stable under the ACA. As of January 2018, 20 states use the option for children and 30 states use it for pregnant women. A total of 15 states are utilizing the new option provided by the ACA to expand presumptive eligibility to other groups, including parents and other adults.

Renewal Processes

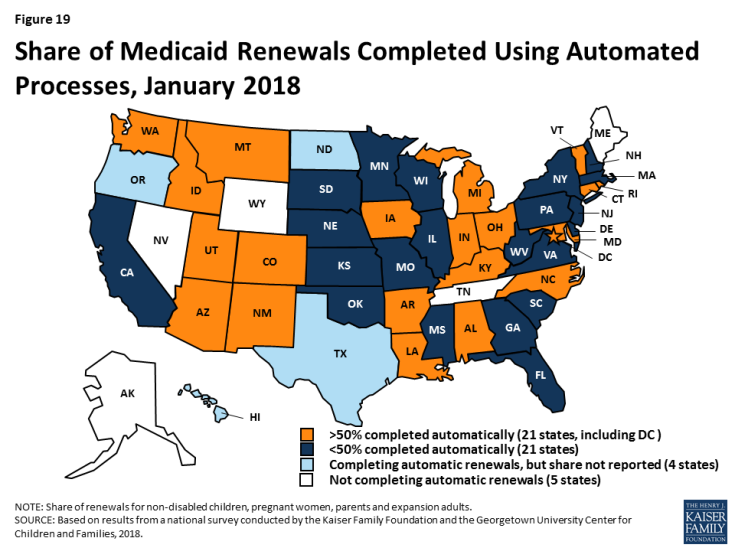

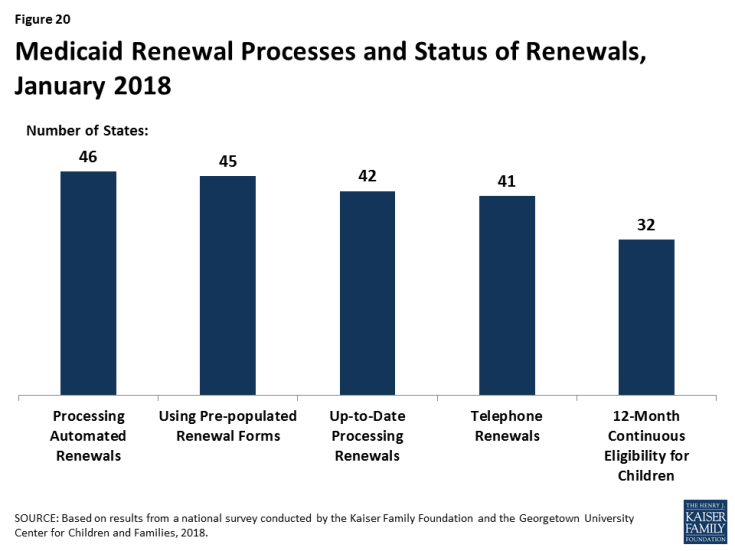

As of January 2018, 46 states use electronic data matches to automatically renew coverage in Medicaid and CHIP without requiring enrollees to submit paperwork. This reflects the implementation of automated renewals in four states (Illinois, Iowa, Oregon, and Wisconsin) during 2017. Similar to data-driven enrollment under the ACA, states are using electronic data matches to renew coverage when possible without requiring an individual to fill out a renewal form or provide documentation. This approach minimizes paperwork for individuals and reduces workloads for states. As of January 2018, among the 42 states completing automated renewals and able to report the share of renewals completed through automatic processes, 21 states reported that more than 50% of renewals are completed automatically, up from 19 in 2017 (Figure 19). This includes seven states that complete more than 75% of renewals automatically. Continued state progress in conducting automated renewals has enabled states to largely resolve backlogs or delays in renewals.

Forty-five states use prepopulated forms to facilitate renewal when a state is not able to complete an automatic renewal through electronic data sources (Figure 20). In 14 states, the state populates the form with updated sources of data from electronic data matches. In cases where the automatic renewal process is unable to affirm ongoing eligibility, 41 states allow individuals to renew by phone, compared to 24 states that offered telephone renewals in 2013.

More than half of states have taken up the option to support stable coverage for children by providing 12-month continuous eligibility. Since prior to the ACA, states have had an option to provide 12-month continuous eligibility for children. Continuous eligibility promotes retention and reduces “churn” – that is, individuals moving on and off coverage due to small income changes, which can be administratively costly and result in gaps in health care access. Many quality measures require at least 12 months of continuous enrollment, so the policy also enhances states’ ability to assess quality of care. As of January 2018, 32 states provide 12-month continuous eligibility to children. In addition, Montana and New York offer 12-month continuous eligibility to parents and other adults under Section 1115 waiver authority.