What to Know About How Medicare Pays Physicians

More than 67 million people—20% of the U.S. population—receive their health insurance coverage through the federal Medicare program. Among the most commonly used services that Medicare covers are physician services and other outpatient services covered under Medicare Part B. In 2021, 9 out of 10 beneficiaries in traditional Medicare used physician and other Part B medical services. Nearly half of the $1 trillion in gross Medicare benefit spending in 2023 (49% or $493 billion) was spent on Part B services. Medicare Part B spending accounts for 25% of all national spending for physician and clinical services.

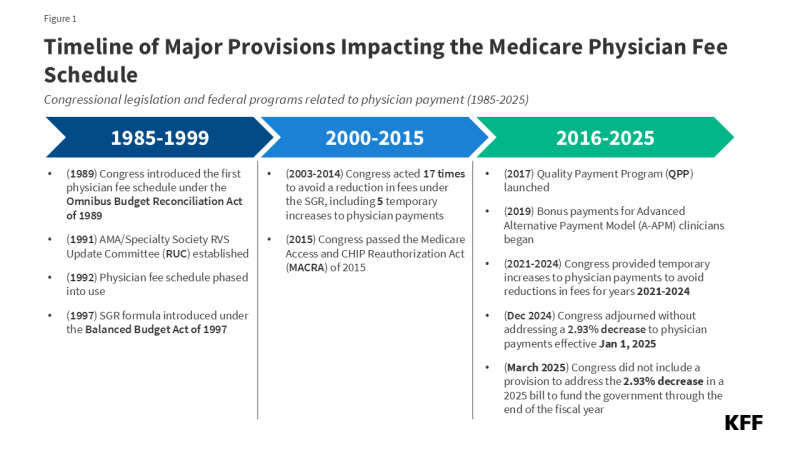

Each year, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) updates Medicare payments for physician services and other Part B services through rulemaking, based on parameters established under law. In November 2024, CMS finalized a 2.83% decrease in the physician fee schedule conversion factor, a key aspect of physician payment rates under the Medicare program. This resulted in an average payment cut of 2.93% to physicians and other clinicians, which took effect on January 1, 2025 and remains in effect today. Congress considered but did not enact legislation to reverse the cut in Medicare physician payments in the year-end spending bill and in the 2025 continuing resolution that funds the government through the end of the fiscal year (Figure 1). Some policymakers continue to push for a fix, which is reportedly under consideration for inclusion in an upcoming budget reconciliation bill.

Efforts by lawmakers to address the Medicare physician payment cut for 2025 are the latest in a series of legislative actions to provide short-term increases to physician payment rates under Medicare to avoid similar reductions in fees. The payment cut finalized for 2025 follows the expiration of temporary funds under the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2024, which provided a 2.93% increase to physician payments for a portion of 2024 to stave off scheduled cuts.

Over the years, physician groups and some policymakers have called for broader reforms to stabilize Medicare payments to physicians and other clinicians, and have expressed concerns that instability and loss of revenue could push physicians to opt out of the Medicare program, creating potential access problems for Medicare beneficiaries. Physicians are not required to take Medicare patients, but most do; virtually all (98%) of non-pediatric physicians accept Medicare’s standard payment rate for all Medicare covered services, and just 1% opted out of the program in 2024.

MedPAC and others have raised additional concerns about issues such as the long-standing gap in compensation between primary care and specialty care clinicians, the efficacy of quality-based payment incentives through the Quality Payment Program (QPP), and the influence of medical specialty groups and interests through the American Medical Association/Specialty Society Relative Value Scale (RVS) Update Committee, otherwise known as the RUC. The RUC issues annual recommendations to CMS on physician payment rates, and CMS has historically adopted most of these recommendations each year. These issues have drawn the attention of policymakers in recent years, including Robert Kennedy Jr., the Trump administration’s new Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), who has voiced interest in aspects of Medicare physician payment reform, such as increasing incentives for primary and preventive care, as well as bringing greater transparency to the operations of the RUC and potentially reducing the AMA’s influence over payment rates.

This issue brief answers key questions about how Medicare pays physicians and other clinicians, and reviews policy options under discussion to reform this payment system. The brief is focused primarily on the physician payment system used in traditional Medicare. Medicare Advantage plans have flexibility to pay providers differently and currently there is no systematic publicly-available information on how much Medicare Advantage plans pay providers. (See Appendix for a glossary of relevant programs, legislation, and terms.)

- What is the Medicare physician fee schedule?

- How does Medicare update physician payment rates?

- What is the role of the RUC in determining physician payment rates?

- How have physician payment rates changed in 2025?

- How did the 2025 payment rule address issues related to primary care, telehealth, and other health care priorities?

- How have Medicare payments to physicians changed since the implementation of MACRA?

- How does the Quality Payment Program (QPP) factor into physician payments?

- What concerns have been raised about the physician fee schedule?

- What policy proposals have been put forward to address concerns with Medicare’s current physician payment system?

1. What is the Medicare physician fee schedule?

Medicare reimburses physicians and other clinicians based on the physician fee schedule, which assigns payment rates for more than 10,000 health care services, such as office visits, diagnostic procedures, or surgical procedures. For services provided to traditional Medicare beneficiaries, Medicare typically pays the provider 80% of the fee schedule amount, while the beneficiary is responsible for a coinsurance of 20%. Physicians who participate in Medicare agree to accept this arrangement as payment in full (known as accepting “assignment”) for all Medicare covered services. Non-participating physicians receive 5% lower Medicare payments, but may accept “assignment” on a claim-by-claim basis and may choose to bill beneficiaries for larger amounts by charging additional coinsurance, up to 15% more than the Medicare-approved amount for the cost of a covered service. A third group of physicians opt out of the Medicare program altogether, and instead enter into private contracts with their Medicare patients, are not limited to charging fee schedule amounts, and do not receive any reimbursement from Medicare. Just one percent of all non-pediatric physicians opted out of the Medicare program in 2024.

Physician fee schedule rates for a given service are based on a weighted sum of three components: (1) clinician work, (2) practice expenses, and (3) professional liability insurance (also known as medical malpractice insurance). These three components are measured in terms of “relative value units” (RVUs). Together these three components represent the overall cost and effort associated with a given service, with more costly or time-intensive services receiving a higher weighted sum. Each component is adjusted to account for geographic differences in input costs, and the result is multiplied by the fee schedule conversion factor (an annually adjusted scaling factor that converts numerical RVUs into payment amounts in dollars). Fee schedule services are each associated with a unique service code, which allows clinicians to seek reimbursement for the care they provide on a service-by-service basis.

Payment rates specified under the physician fee schedule establish a baseline amount that Medicare will pay for a given service, but payments may be adjusted based on other factors, such as the site of service, the type of clinician providing the service, and whether the service was provided in a designated health professional shortage area. Physicians can also receive quality-based payment adjustments under the Quality Payment Program (QPP) (see question 7).

2. How does Medicare update physician payment rates?

Annual updates to the physician fee schedule include statutorily-required updates to the conversion factor under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) (see question 6), as well as other adjustments to reflect the addition of new services, changes in input costs for existing services, and other factors. Included in these adjustments are periodic changes to the RVUs assigned to fee schedule service codes, based in part on the recommendations of a multispecialty committee of physicians and other professionals, known as the AMA/Specialty Society RVS Update Committee (RUC) (see question 3).

Under current law, the projected cost of all changes to the physician fee schedule must be budget neutral. That is, the changes may not raise total Medicare spending by more than $20 million in a given year. This requirement was established by the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1989 to address concerns that constraints on physician fees for specific services would lead to increases in service volume and growth in Medicare spending for physician services over time. The law requires CMS to adjust fee schedule spending when projected costs exceed the $20 million threshold, typically by decreasing the conversion factor relative to the statutory update called for by MACRA.

3. What is the role of the RUC in determining physician payment rates?

The AMA/Specialty Society RVS Update Committee (RUC) is a volunteer committee of physicians and other professionals, formed by the American Medical Association (AMA) in 1991 to advise CMS on the relative weighting of service codes under the physician fee schedule, the primary mechanism used by CMS to set relative payments for physician and clinical services. The RUC is an independent body and its operations are not directly overseen by Congress or CMS. Further, because the RUC is not an official federal advisory committee, it is not bound by federal standards around transparency, membership balance, and other operating requirements applied to many similar committees. The RUC includes representatives from the AMA and other professional organizations, as well as members appointed by a range of national medical specialty societies.

Each year, CMS identifies potentially misvalued services for RUC review based on statutory criteria and public nomination. Potentially misvalued services may also be identified by the RUC itself, while new or recently revised service codes are identified by a separate AMA panel, known as the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) Editorial Panel. The RUC then consults with various medical specialty societies, who decide which services they wish to review and develop recommendations on the clinician work, practice expenses, and other factors associated with payment for each service. A final list of recommendations for reviewed services is compiled by the RUC based on a committee vote and referred to CMS.

CMS is not required to adopt recommendations issued by the RUC, but it does so in a majority of cases. The AMA reports an average annual acceptance rate of 90% from 1993 to 2025. Over the years, MedPAC and others have raised concerns about the influence of the RUC, which is largely composed of specialty physicians with a financial stake in the recommendations they are producing, and noted several methodological issues with the data used to develop RUC recommendations (see question 8). MedPAC has called for CMS to develop internal processes to validate RUC recommendations by independent means. More recently, HHS Secretary Kennedy has raised concerns about the lack of transparency and relative lack of oversight of RUC operations by CMS, as well as the influence of the AMA in setting payment rates for physicians, which has brought renewed attention to the issue (see question 9).

4. How have physician payment rates changed in 2025?

CMS recently finalized payment changes for 2025, which include a 2.83% decrease to the physician fee schedule conversion factor relative to 2024. This decrease reflects the following adjustments: (1) the expiration of temporary funds approved by Congress under the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2024, which increased payments by 2.93% for all fee schedule services furnished between March 9, 2024 and December 31, 2024, (2) a 0% statutory increase for 2025 under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), and (3) a modest 0.02% budget neutrality adjustment. The combined impact of these adjustments is a 2.93% decrease in average payments to physicians and other clinicians, which went into effect on January 1, 2025.

As of March 2025, Congress has not passed legislation to address this payment cut. A provision to reduce (though not fully eliminate) the cut was included in an early version of the year-end Continuing Resolution (CR) filed in December 2024, similar to the temporary payment adjustments instituted by Congress in prior years, but was removed from the version signed into law. Congress also considered, but did not include, legislation in the subsequent CR enacted in March 2025, but some policymakers continue to push for a fix, which is reportedly under consideration for inclusion in an upcoming budget reconciliation bill.

5. How did the 2025 payment rule address issues related to primary care, telehealth, and other health care priorities?

Recent changes to the physician fee schedule also include several measures designed to improve health care access and increase support for preventive services, behavioral health, and management of chronic disease. These measures are part of an ongoing effort by CMS and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to strengthen primary and preventive care and address long-standing concerns about the gap in compensation between primary and specialty care physicians (see question 8). The final payment rule for 2025 introduces the following key changes:

- CMS has added new billing codes to the physician fee schedule intended to streamline payment for advanced primary care management. This change bundles several existing services related to care management, interprofessional consultation, and other care components into single codes, stratified by patient medical and social complexity, which may be billed on a monthly basis.

- CMS has added new billing codes related to caregiver training for direct care services and supports, allowing clinicians to bill for time spent training caregivers on specific clinical skills such as techniques to prevent ulcer formation, wound dressing changes, and infection control, and has expanded existing billing options for trainings dedicated to caregiver behavior management and modification.

- CMS has finalized several provisions aimed at improving beneficiary access to telehealth, such as broader coverage of audio-only services and increased flexibility in the use of telehealth for treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD). Safety planning interventions and PrEP counseling have been added to the Medicare Telehealth Services list on a permanent basis, and caregiver training services have been added on a provisional basis.

- Absent further action from Congress, many of the other telehealth restrictions that were in place prior to the COVID-19 pandemic will come back into effect on April 1, 2025. These include restrictions limiting telehealth coverage to beneficiaries in rural areas, and requiring beneficiaries to travel to an approved site, such a clinic or doctor’s office, when receiving telehealth services. However, CMS has extended certain limited flexibilities under its authority through December 2025, such as provisions that allow Rural Health Centers (RHCs) and Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) to serve as distant site providers for all covered telehealth services, and allow providers to use their currently enrolled practice location in place of their home address when providing telehealth services from home.

- CMS has also added new billing codes for a range of other primary and behavioral health services, such as cardiovascular risk assessment and care management, use of digital mental health treatment devices, and safety planning interventions for patients at risk of suicide or overdose, among others.

- CMS has finalized several updates to the Quality Payment Program (QPP) to improve the accuracy of quality reporting and reduce administrative burden for providers participating in the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). (For a more detailed description of the QPP and MIPS, see question 7).

The new rules also include updates to the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), a permanent accountable care organization (ACO) program in traditional Medicare that offers financial incentives to providers for meeting savings targets and quality goals, as well as other changes related to payment for preventive vaccine administration, opioid treatment programs, evaluation and management of infectious diseases in hospital inpatient or observation settings, and a variety of other health services.

6. How have Medicare payments to physicians changed since the implementation of MACRA?

Medicare has revised its system of payment for physician services numerous times over the years (Figure 1). The current payment system was established under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) and includes two primary components: (1) a schedule for annual, statutorily-defined updates to the conversion factor, a key determinant of payment rates under the physician fee schedule, and (2) a new system of bonus payments and quality-based payment adjustments under Quality Payment Program (QPP) (see question 7).

The physician payment system established by MACRA was intended to stabilize fluctuations in payment caused by the prior system under the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) formula, which set annual targets for Medicare physician spending based on growth in the gross domestic product (GDP). Under the SGR, if physician spending exceeded its target in a given year, payment rates would be cut the following year, while spending that was below the target led to increased rates. As with the current system, rates were subject to further adjustment for budget neutrality if the projected cost of all fee schedule spending was projected to increase by more than $20 million for the year.

The SGR was established by the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 to slow the growth in Medicare spending for physician services, but the formula garnered criticism, as growth in service volume and rising costs led to several years of spending on physician services that exceeded the growth target, necessitating payment cuts from 2002 onward. Between 2002 and 2015, Congress enacted 17 short-term interventions (so-called “doc-fixes”) to delay the cuts and provide temporary increases to physician payments, but did so without repealing the SGR, which resulted in accumulated deficits over time.

MACRA permanently eliminated the SGR formula, preventing a 21.2% cut in physician fees slated for 2015 and replacing it with 0% statutory increases to the conversion factor through 2025 (later raised to 0.5% from 2016-2019), followed by modest annual increases from 2026 onward. These updates are set by MACRA and do not vary based on underlying economic conditions. However, subsequent adjustments to preserve budget neutrality and supplemental payments provided by Congress may result in conversion factor updates that are higher or lower than the statutorily-required update in a given year.

Although MACRA has stabilized payments under the physician fee schedule to some degree relative to the years leading up to its enactment, rates have continued to fluctuate over the last decade. Due to strict budget neutrality requirements, CMS has limited flexibility to adjust payment rates for new or undervalued services without offsetting the costs elsewhere in the fee schedule. This often takes the form of budget neutrality adjustments to the conversion factor, such as a -10.20% adjustment in 2021 and a -2.18% adjustment in 2024. Since 2021, Congress has provided several short-term increases to fee schedule rates to boost payment during the COVID-19 pandemic and to offset budget-neutrality cuts, raising concerns that the cycle of “doc-fixes” under the SGR formula has not been wholly avoided under MACRA.

7. How does the Quality Payment Program (QPP) factor into physician payments?

The Quality Payment Program (QPP), which launched in 2017, was established by the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) to create financial incentives for health care providers to control costs and improve care quality. The QPP includes two distinct pathways for participation: (1) incentive payments for participants in qualified advanced alternative payment models (A-APMs) and (2) performance based payment adjustments under the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS).

A-APM Incentive Payments: Physicians and other clinicians who participate in qualified A-APMs, such as select accountable care organizations (ACOs) and others, are eligible for bonus payments if they meet certain participation thresholds. A-APMs are a type of value-based care model in which the provider bears some financial risk for the costs of care in a defined setting, such as treatment of a specific condition or primary care services for a group of beneficiaries, typically by sharing in a portion of financial savings and losses relative to a benchmark. Incentive payments to increase participation in A-APMs are part of a broader goal by CMS to have all traditional Medicare beneficiaries in some type of accountable care relationship by 2030.

Each year, A-APM clinicians qualify for bonus payments based on their participation during the Qualifying APM Participant Performance Period (January 1 – August 31) two years prior. Under MACRA, qualifying A-APM clinicians received a 5% bonus in payment years 2019 through 2024 (performance periods 2017 – 2022). Congress subsequently extended these bonus payments to include a 3.5% bonus in 2025 and a 1.88% bonus in 2026. A-APM bonus payments are scheduled to be phased out in favor of annual 0.75% increases to the conversion factor for qualifying A-APM clinicians (relative to smaller 0.25% increases for all other clinicians). These conversion factor updates will begin in 2026, and A-APM bonus payments will be fully retired in 2027.

Roughly 386,000 clinicians qualified for A-APM bonuses in 2024, based on the 2022 performance period, a nearly fourfold increase from 99,000 in 2019, the first year A-APM bonuses were available. At the same time, A-APMs are not evenly distributed throughout the country, and participation among non-physician providers and certain physician specialties remains relatively low, suggesting that additional strategies may be needed to encourage wider adoption of these models. Further, MedPAC and others have noted that the scheduled conversion factor updates for qualifying A-APM clinicians will be relatively small in the first few years after A-APM bonuses are retired, though their effects will compound over time, and have cautioned that additional incentives may be needed to prevent attrition in A-APM participation during this transition.

Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS): Clinicians who do not participate in A-APMs, or do not meet the participation criteria for A-APM bonus payments, are subject to additional reporting requirements under MIPS, which adjusts payments up or down depending on a clinician’s performance on certain quality metrics. As with A-APM bonuses, payment adjustments under MIPS are based on performance two years prior. Clinicians are required to participate in MIPS if they are eligible, but many are exempt, such as those in certain specialties (e.g., podiatrists), those in their first year of Medicare participation, and those who serve a low volume of Medicare patients.

Payment adjustments under MIPS are required to be budget neutral. Adjustments are capped each year (between +9% and -9% in 2025), and savings generated from clinicians who incur negative adjustments are used to fund positive adjustments for those who qualify. Because a relatively small share of clinicians have incurred negative adjustments each year since MIPS was implemented, positive adjustments have generally been much lower than the annual cap. In 2023 for instance, roughly 600,000 clinicians received positive adjustments up to +2.34%, based on the 2021 performance year, while just 23,000 clinicians received negative adjustments down to -9%. MedPAC estimates that another 460,000 clinicians were ineligible for either an A-APM bonus or MIPS adjustment due to low Medicare patient volume or other exemption criteria.

Clinicians who participate in MIPS have traditionally selected from a large set of quality measures and other clinical metrics to report on each year. While this structure was intended to give clinicians flexibility to choose the metrics best suited to their practice, it has also been criticized by physician groups and experts for increasing the reporting burden on participants, and for making comparisons between participants less clinically meaningful and more difficult to assess. In an effort to address these concerns, CMS has introduced several more streamlined reporting options. The newest of these allows clinicians to choose from smaller, bundled subsets of reporting metrics tailored to particular specialties or medical conditions, known as MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs).

MVPs were introduced in 2023 as an optional alternative to reporting under traditional MIPS, and included a preliminary set of reporting pathways aimed at specific clinical contexts, such as primary care, treatment of heart disease, and supportive care for neurodegenerative conditions. CMS has added new MVPs each year since the option was introduced, including 6 in 2025, with the eventual goal of replacing all reporting under traditional MIPS with MVPs in future years. The purpose of this shift is to reduce administrative burden by offering providers smaller, more targeted sets of reporting metrics to choose from, as well as to allow for more clinically meaningful assessments by comparing outcomes among similar clinicians who choose to report under the same MVP.

8. What concerns have been raised about the physician fee schedule?

Criticism of the physician fee schedule has focused on four primary concerns about the way in which Medicare pays physicians and other clinicians. These include: (1) the overall adequacy of Medicare payments to cover medical practice costs and incentivize participation in the Medicare program, (2) the gap in compensation between primary and specialty care clinicians, (3) the influence of the AMA/RVS Update Committee (RUC) and medical specialty groups in determining relative payment rates for fee schedule services, and (4) the success of the Quality Payment Program (QPP) in achieving its goal of incentivizing quality improvements and cost-efficient spending.

Payment Adequacy: Over the years, physician groups and some policymakers have expressed concern that payment rates under the physician fee schedule have not kept pace with inflation in medical practice costs. Practice expenses are one component of the relative-value calculation used to determine payment rates for fee schedule services, but the requirement to preserve budget neutrality makes it difficult for CMS to increase payment for some services without also decreasing payment in other areas, such as by lowering the fee schedule conversion factor (see question 6). Statutory increases to the conversion factor under MACRA are not scheduled to begin until 2026, and do not vary based on underlying economic conditions, which may make it more challenging for some physicians to adapt to changing financial demands.

Core to these concerns is the possibility that loss of revenues could lead some physicians to opt out of the Medicare program, which could create access issues for Medicare beneficiaries. National surveys and other analyses have generally found that beneficiaries report access to physician services that is equal to, or better than, that of privately-insured individuals, with similar or smaller shares reporting delays in needed care or difficulty finding a physician who takes their insurance. A recent KFF analysis found that just 1% of all non-pediatric physicians had opted out of Medicare in 2024, suggesting that the current fee structure has not substantially discouraged participation. Moreover, MedPAC estimates that virtually all Medicare claims (99.7% in 2023) are accepted on “assignment” and paid at the standard rate (see question 1), with beneficiaries in traditional Medicare facing no more than the standard 20% coinsurance rate. At the same time, analyses by KFF and others have found that physicians in some specialties, such as psychiatry, opt out of Medicare at higher rates, which may impact access to these services over time.

Loss of revenue may also lead some physician practices to merge with (or be acquired by) larger health systems or hospitals, a process known as “vertical consolidation.” Vertical consolidation may offer certain benefits to physicians, such as greater economy of scale for practice expenses, lower administrative burden, and access to costly resources such as medical imaging equipment, and may be attractive to physicians who are otherwise struggling to meet their practice costs. While consolidation may be associated with some benefits to patients as well, such as improvements in care integration and coordination between providers, it may also lead to higher out-of-pocket costs and lower care quality by reducing market competition. Further, Medicare generally pays more for a given service provided in a hospital outpatient department than it does for the same service provided in a freestanding physician office, which can lead to increased costs for beneficiaries and higher program spending over time. Policymakers are currently exploring options to align Medicare reimbursement rates between these settings, known as “site-neutral payment reforms.”

Primary Care Compensation: A second concern with the current payment system is that Medicare does not adequately pay for primary care services, as reflected by the gap in Medicare payments between primary and specialty care clinicians. Payments under the physician fee schedule are generally higher for clinical procedures, such as surgeries and diagnostic tests, than for non-procedural services, such as preventive care provided during an office visit. While many clinicians provide a mixture of procedural and non-procedural services, primary care clinicians often dedicate a larger share of their time to non-procedural care. Further, MedPAC has expressed concern that this imbalance encourages clinicians of all specialties to increase their use of more costly and profitable services, such as unnecessary imaging, screenings, and diagnostic tests, at the expense of high-value, but less profitable, services, such as patient education, preventive care, and coordination across care teams, which can impact the quality of patient care and lead to higher physician spending over time.

MedPAC notes that clinical procedures often see gains in efficiency due to technological improvements and other factors, which reduce the time and effort needed to provide them. If fee schedule rates are not adjusted to reflect these improvements, these services may become overvalued over time. By contrast, non-procedural services often involve more fixed time constraints, such as time spent communicating with patients or coordinating with other providers, and are unlikely to see similar gains, contributing to the gap in compensation between these service types.

Due to budget neutrality requirements, efforts to directly increase payment for non-procedural services under the physician fee schedule in order to boost payments for primary care have often necessitated across-the-board payment cuts in the form of decreases to the fee schedule conversion factor (see question 6). Further, physicians may offset any expected reductions in revenue by increasing service volume over time, or by increasing their use of higher intensity, and more highly compensated, service codes, leaving the gap in payment rates relatively constant. These constraints make it difficult for CMS to meaningfully address differences in payment between primary and specialty care, and have led some policymakers to voice concerns that the current budget neutrality requirements are too rigid.

Role of the RUC: The American Medical Association (AMA) and the RUC play a substantial role in annual decision-making around the relative weighting of service codes under the physician fee schedule, the primary mechanism used by CMS to set relative payment rates for physician and clinical services (see question 3). While CMS is not required to adopt recommendations issued by the RUC, it does so in a majority of cases. MedPAC has raised several methodological concerns with the data used by the RUC to develop its annual reports, which are largely based on recommendations from medical specialty societies. These include a lack of transparency, as well as low response rates and total responses on the various member surveys that inform medical specialty society recommendations, which make it difficult for CMS to validate RUC recommendations by other means.

Other concerns raised about the RUC include the overrepresentation of specialty physicians on the committee, and the potential for conflicts of interest when RUC members recommend changes to relative payments for primary and specialty care services. In contrast to federal advisory committees, which are typically formed by Congress, the office of the President, or executive branch agencies, the RUC is an independent committee overseen by the AMA. For this reason, it is not held to the same operating requirements as many other similar committees, which adhere to certain criteria around transparency and membership balance.

To ensure that fee schedule services are not overvalued, MedPAC has recommended that CMS develop internal processes for validating RUC recommendations, such as by collecting data from clinical practices on the number of clinician hours dedicated to commonly-billed services. Pilot studies commissioned by CMS and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) have attempted to validate the clinician time component of small subsets of fee schedule services using methods such as analysis of electronic health records, direct observation of clinical procedures, and independently-collected physician surveys. These projects may serve as a blueprint for future work, though implementing these and similar methods on a large scale would likely require significant time and staff investment.

Role of the QPP: QPP programs such as the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and bonus payments for Advanced Alternative Payment Model (A-APM) clinicians are designed to create incentives for quality improvement, care coordination, and the provision of high-value services (see question 7). While the share of clinicians who qualify for A-APM bonuses has more than tripled since the QPP began (from roughly 99,000 to 386,000 in the 2017 and 2022 performance periods, respectively), some policymakers have argued that greater incentives are needed to encourage providers to take on the financial risks and high startup costs associated with these models, particularly as A-APM bonus payments are phased out in favor of relatively smaller conversion factor adjustments in the coming years.

Additionally, MedPAC has voiced concern that MIPS, the quality-based payment program for clinicians who do not participate in A-APMs, imposes too large of a reporting burden on those who participate, while at the same time offering relatively weak incentives to improve quality and control costs. As noted earlier, a large share of clinicians are exempt from the program, and because few participants receive negative adjustments, positive adjustments are relatively modest. The administrative burdens associated with MIPS may be partially addressed by the shift towards MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs) in place of traditional quality reporting, and further assessment of this option will likely take shape as the program is phased in.

9. What policy proposals have been put forward to address concerns with Medicare’s current physician payment system?

In addition to bipartisan legislation that directly addresses the 2025 payment cuts that took effect January 1, 2025, policymakers and others have put forward a number of strategies to revise the current Medicare physician payment system. These include measures to stabilize physician fee schedule payments from year to year, provide additional support to primary care and safety-net providers, and create stronger incentives for efficient spending, care coordination, and participation in Advanced Alternative Payment Models (A-APMs).

In 2025, MedPAC recommended a one-time inflation-based increase to physician payment rates in 2026 (equal to the projected increase in the Medicare Economic Index minus one percentage point), similar to recommendations from past years. While MedPAC has weighed the possibility of recommending annual updates for inflation, it has not done so to date, focusing instead on targeted strategies to bolster payments to primary care clinicians and safety-net providers. For instance, in light of findings that clinicians often receive lower revenue for treating low-income Medicare beneficiaries, MedPAC has recommended raising payment in these instances by 15% for claims billed by primary care clinicians and 5% for claims billed by non-primary care clinicians, to encourage clinicians to treat these populations.

MedPAC has voiced support for the goals behind the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) and the Quality Payment Program (QPP), including the financial incentives offered to A-APM participants under current law (see question 7), while also recommending changes to the design of the QPP, including the elimination of the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). MedPAC has noted that the ongoing shift from traditional MIPS to MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs) addresses some concerns related to administrative complexity and participant comparisons, but a large share of clinicians remain exempt from MIPS reporting and incentive payments have generally remained relatively small (see question 8). In place of MIPS, MedPAC has recommended establishing a voluntary program designed to mimic the structure of A-APMs and other alternative payment models, allowing clinicians to transition into these models more gradually.

Several bills introduced in the last Congress indicate interest in strategies such raising or modifying the budget neutrality threshold, or offering separate conversion factor updates for primary and specialty care services, which would allow CMS greater flexibility to adjust payment rates to reflect evolving policy priorities without necessitating a mandatory payment cut. The Senate Finance Committee has held several hearings on physician fee schedule reform, and released a whitepaper in 2024 outlining a range of options to stabilize conversion factor updates from year to year, extend access to telehealth, and incentivize continued participation in A-APMs, among other reforms.

More recently, House Republicans included adjustments to the physician fee schedule in a menu of potential policy actions circulated in January 2025. The Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Robert F. Kennedy Jr., has expressed a particular interest in Medicare physician payment reform, and has called for bringing greater transparency to the operations of the AMA/RVS Update Committee (RUC) (see question 3), as well as exploring options for reducing the role the RUC plays in annual decision-making around physician payments.

A decade after the passage of MACRA, Congress’s last major overhaul of how Medicare pays physicians, interest in broader reforms to Medicare’s physician payment system, beyond addressing the physician fee cuts finalized for 2025, is gaining steam. Designing payment approaches that address concerns raised by interested parties to compensate physicians adequately while restraining spending growth represents a challenge for policymakers.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.