Family Consequences of Detention/Deportation: Effects on Finances, Health, and Well-Being

Introduction

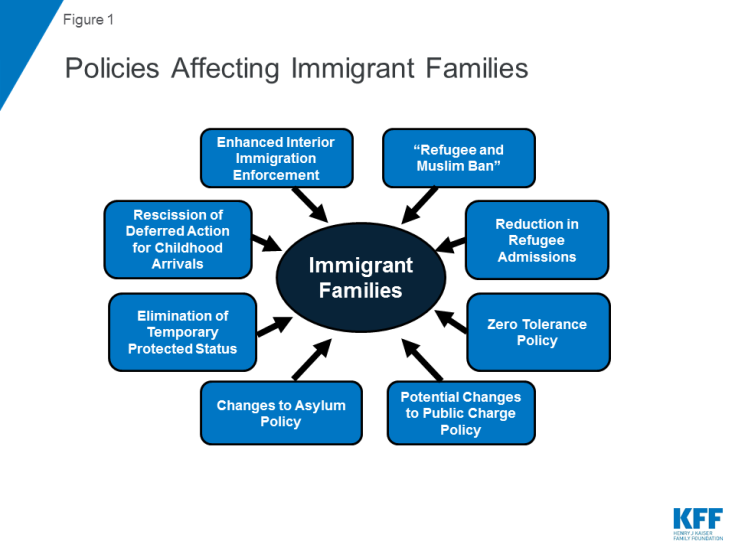

An array of Trump Administration policies currently are affecting immigrant families, including policies to enhance interior immigration enforcement, restrict entry into the U.S., and decrease use of public programs by immigrants and their U.S.-born children (Figure 1). As documented in a previous Kaiser Family Foundation report, these policies, along with growth in anti-immigrant sentiment, have significantly increased fear and uncertainty among immigrant families and had wide-ranging negative impacts on their health and well-being. This report builds on that work by exploring the direct impacts of detention and deportation on the finances, health, and well-being of families.

The findings are based on structured interviews with 20 individuals who recently had a family member in their household detained or deported that were conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation, working with PerryUndem Research/Communication, during Summer 2018. The interviews were conducted in five cities in three states, including, Sunnyvale, Fresno, and Los Angeles, California; Washington, DC; and Houston, Texas. In addition, 12 telephone interviews were conducted with legal services providers, health centers, educators, and community-based organizations serving immigrant families in these states. The Blue Shield of California Foundation supported the work in California.

Findings

Overview of Families

Most respondents were Hispanic women with children in the home. The ages of children ranged from infants and toddlers to teenagers. Immigrants in respondents’ families primarily came to the U.S. from Mexico and Central America, including El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala. Most frequently, the respondent was the spouse or partner of the detained or deported individual. However, respondents also included parents of an adult child who was detained or deported, teenage or adult children of a detained or deported individual, and an adult sibling of a detained or deported individual. Although participating families predominantly came from Mexico and Central America, stakeholders served immigrant families from a broader array of countries. They noted that, although there is less attention on the effects of immigration enforcement on other communities, they also are experiencing many of the same impacts.

Family members of detained or deported individuals had varied immigration statuses, but most children in the households were U.S.-born. Some adults were U.S. citizens, including U.S.-born and naturalized citizens. Others had varied statuses, included legal permanent residents (“green card” holders), Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipients, and individuals with temporary protected status (TPS). Some were undocumented, although a number were seeking legal permanent residency or asylum. In most cases, children in the households were U.S. born.

Respondents said their families came to the U.S. to seek safety and escape violence; some survived trauma in their home countries or during their journey to the U.S. One woman’s son had been killed in her home country. Another had received direct death threats to her family, including her six-year-old child. A few were survivors of domestic violence. One woman was kidnapped by human traffickers while entering into the U.S., and released after her family paid a ransom. Stakeholders noted that the trauma of detention or deportation of a family member often compounds previous trauma.

| “[The gangs] were coming after us… On the last call they told us… they were going to start killing the youngest of the family. And the youngest was my daughter.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Fresno, CA

“They pulled a gun on me. They wanted to kill me. And they robbed me and told me that if they saw me in the street, they’d kill me….” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, DC Area “Many of our families…make huge sacrifices in their home countries in order to get here and then the process of actually coming can be extremely traumatic… we have some extreme horror stories about peoples’ migration process.” Educator, DC Area |

Growing Fear of Enforcement

Stakeholders reported that enforcement activity has become more arbitrary, increasing fear among the community. They indicated that enforcement previously focused on individuals with a criminal history, particularly those who committed violent crimes. In contrast, today, everyone is a priority. They also have observed an increased focus on people who have been living in the U.S. for longer periods, sometimes decades. Legal services providers noted that the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) is now referring people to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) if they deny a claim for status. They also noted that fewer people will be able to obtain asylum due to recent policy changes to reject claims based on domestic or gang-related violence. Stakeholders and families reported that the expanding nature of current enforcement activities, as well as recent raids in communities and homes, have increased fears among the broad immigrant community.

| “…in the past they might’ve really been focused on…people with criminal histories… Those people are still getting removed, but not as many in proportion to the overall numbers, because…everybody’s a priority now…” Legal Services Provider, CA

“…before they would just go after criminals or people that have only been in the country for a couple years. And now, grandmas are getting deported. And so that fear of…it could be anybody, it could happen at any time.” Health Center, CA “…because of Sessions’ new policy of not honoring domestic violence or gang-related violence as a legitimate asylum claim, we’re seeing lots and lots of folks … feel like they don’t have any hope.” Health Center, DC Area |

Families and stakeholders reported growing concerns and fears among DACA recipients and individuals losing TPS status. They said that individuals are increasingly fearful that ICE will target them when they lose status because the government has their information. They noted that they feel scared, uncertain, and hopeless about their future and fear returning to a country to which they have no connection since they have lived in the U.S. for decades and established their lives and families here.

| “I wanted to renew [my TPS], but by next March, we won’t have it anymore. We’re all afraid…because they have your address, everything.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, DC Area

“So a lot of my TPS clients…are just devastated. They just feel that the country has turned their backs on them, that they have been in this community for some of them 25 years.” Legal Services Provider, TX “We’ve seen…an increase in hopelessness…just kind of feeling trapped…because the thought of going back to a country that they [DACA recipients] don’t have any connections to…” Educator, DC Area |

Stakeholders also observed increased fears among legal permanent residents and naturalized citizens. Some stakeholders reported an uptick in legal permanent residents seeking citizenship because they no longer feel secure with their status. Families and stakeholders also said that growing anti-immigrant sentiment has led to uneasiness in the community regardless of status.

| “I’ve noticed that a lot of people who have been permanent residents for 20, 25 years are now coming and asking for, to apply for citizenship. …they’re fearful that even as legal permanent residents they could be deported…” Legal Services Provider, TX

“…there’s a lot of hate going around us Mexicans…. And I’m scared…because, in the back of your head you’re thinking that you might encounter these people with hatred, with racism….” Adult Daughter of Detained/Deported Individual, Houston, TX |

Detention and Deportation of Family Members

Detention and deportation of family members occurred suddenly and unexpectedly, leaving families in shock and unprepared. Among respondents, the most common circumstances leading to detention or deportation of their family member was during a scheduled check-in or appointment for a pending immigration case or following a traffic stop or other interaction with the police. Respondents said family members went into scheduled immigration visits optimistic and hopeful about progressing forward with their case, but were detained or deported due to inaccuracies or missing information in their case, which sometimes related to issues from decades ago. Several families said these gaps or inaccuracies were due to mistakes or failures by their attorneys. Some detained or deported family members had been living in the U.S. for decades, while others had arrived recently.

| “…we both had an appointment for the residency. We went in and then we were in the same office, and after 10 minutes they took him away…” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Los Angeles, CA

“…he…was coming back from work and the police stopped them because one of the lights of his car wasn’t working, and he was detained….” Mother of Detained/Deported Individual, Houston, TX |

Families faced significant costs and challenges to communicate with their detained or deported family member. In several cases, respondents said it was very difficult to find their family member after ICE detained them, noting that they searched the internet, made calls, and sometimes visited facilities in person to locate their family member. Families and stakeholders noted that individuals in detention facilities are not able to receive incoming calls. As such, families must place money into accounts for them to make outgoing calls, which are costly. One family said that they were placing $100 per week into an account, which covered about 2-3 phone calls per week. Families also faced challenges visiting detention facilities. Only family members with legal status can visit a facility and visits can require significant time and costs because sometimes individuals are detained hours away from their family. Families with a deported family member communicated via phone or WhatsApp. The frequency of contact varied; in some cases, it was very limited because the deported family member did not have a phone.

| “…at first we didn’t know…where he was… We had to look him up online…just try different combinations of his name. Me and my older sister…we physically went in there and asked, ‘is my brother here?’” Sibling of Detained/Deported Individual, Fresno, CA

“…they have to pay to call….and now we don’t have a lot of money, so sometimes I can’t give him much, so that’s why he says he’ll talk to me once every two weeks.” Mother of Detained/Deported Individual, Houston, TX “I had to take the five kids to see him, but just once because it’s so expensive to go there–$400 I had to pay to go see him.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, DC Area |

Sudden and Severe Financial Hardship

One of the most immediate and significant effects on families was the loss of income, which left them struggling to pay their bills. Remaining family members often attempted to make up for the lost income by working more hours or picking up additional jobs. For example, one mother reported working a 17-hour day, starting at a chicken packing plant from 5:00am to 4:15pm and then cleaning a church from 5:00 to 10:00pm. However, all respondents had significant difficulty paying their bills due to the loss of income. They cut back on as many expenses as possible, but some did not know how they were going to pay their rent and were behind in their utility payments, with a number at risk of having their utilities cut off. Stakeholders said that, in some cases, individuals have returned to an abusive relationship or suffered poor working conditions or exploitation by an employer because their income needs were so urgent and they had no other options.

| “We have to do the impossible to have food for the kids and try to pay for the bills on time.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Fresno, CA

“At night [the children] still wear diapers, so they don’t wet the bed. I don’t even have money for that. It is very hard. Before it wasn’t like that.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Houston, TX “…we’ve had other patients who…had to go back with an abusive partner…because they just didn’t have any other options.” Health Center, CA |

Many families faced the dilemma of needing to work more hours to pay their bills but not having anyone to care for their children. This situation forced some families into very difficult situations. For example, some parents had to stop working or cut back on their hours since their spouse or partner was no longer available to watch the children but then were unable to pay their bills. One mother sent her two U.S.-born children to Mexico to be with her deported husband, because she could not work the hours necessary to support her family and care for the children at the same time. In addition, some families faced gaps in caregiving support for older adults when an adult child who was providing financial and caregiving support to older parents was detained or deported.

| “So we looked at lots of different options to find a solution, and the only solution was to send [the youngest children] to Mexico and for me to get two jobs.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Los Angeles, CA

“…if I have to work at night, they have to stay somewhere else. Before that wasn’t a problem because their dad was there and stayed with them.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Houston, TX |

Many families reported problems affording food, with some adults going hungry so their children could eat. Many respondents reported at least one of four problems affording food, with a number experiencing multiple or all of these problems (Figure 2). Several respondents said they sometimes go hungry so that their children can eat. Most respondents said they are eating less healthy food to save money. They are eating fewer fruits, vegetables, and meats and relying on rice and beans and canned food. Some got help from family, food banks, churches, or community organizations. Most were not participating in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP or food stamps) or Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program even though their U.S.-born children would likely qualify because they were scared to enroll.

| “Sometimes I would skip a meal so that my kids could eat.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, DC Area

“…right now the girls are asking for fruit. [My daughter] likes to eat fruit, but I don’t have money to go buy her any.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Houston, TX “I used to buy two gallons of milk. Now I only buy one and try and make it last.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Los Angeles, CA |

Some families also experienced unstable housing situations. A number moved in with family or to smaller spaces, which led to crowded living situations and increased stress. One mother became homeless for six months. She stayed with family and friends, moving frequently, which required her children to change schools three times. She moved into an apartment after receiving assistance from a community organization but is uncertain how she will pay rent when that assistance ends.

| “I couldn’t pay for an apartment on my own. [So I had to] move to a room, to live in one room with my three kids…” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, DC Area

“Six months we were homeless… One day here, one day there, we woke up sleeping with relatives…” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Los Angeles, CA |

In some cases, families lost their source of transportation. Without a car, they had to rely on public transportation and/or family or friends for rides. Loss of the car increased the time, hassle, and costs to complete daily tasks like grocery shopping, commuting to work, and getting to medical appointments.

| “…he was the one who would drive, who would take them to the doctor, to the dentist… Now I take the kids to the school, we walk and have to get up earlier.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Fresno, CA |

Disruption to Children’s Routines and Relationships

Families and stakeholders said children are spending more time inside and participating in fewer activities because adults are working all the time and/or more fearful of spending time outside. Some families reported that children became angry or resentful about the remaining parent working all the time. Families and stakeholders also noted that some parents have less patience with their children because of the increased work and stress.

| “I cannot take them to the park; I cannot take them outside…so they stay at home with their videogames.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Fresno, CA

“…before [my daughter-in-law] had more time to help [my granddaughter] with her school stuff and everything…and now, she doesn’t.” Mother of Detained/Deported Individual, Sunnyvale, CA “…when [my daughter-in-law] gets home, she’s very tired. If the kids are awake, she doesn’t even want them to talk to her because she only wants to rest… And she’s always upset with the kids. She doesn’t want them to make noise, doesn’t want them to bother her…” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Fresno, CA |

In some families, older children assumed new responsibilities and changed their plans for the future. For example, some older children took on jobs to help support the family or expanded roles caring for their younger siblings. Stakeholders noted that, in some cases, older children have taken on challenging and stressful roles advocating and translating for their parents to communicate with lawyers and others involved in their family’s immigration case. Some families reported that older children changed their plans for the future. For example, one declined acceptance to a university and is attending community college because the family can no longer afford the university. Another is revaluating plans to join the armed forces because she feels she should get a job to help support the family.

| “…kids aged 14, 15, 16… many times they become in charge of not just of themselves, but of the little siblings…” Health Center, CA

“…sometimes the kids they’ll…take on roles that a kid maybe shouldn’t take on, like speak, translate for their parents and for a lawyer or for the police…so, they’re having to take on difficult roles.” Community Organization, TX “…he wants to go to college, but we decided it is better if he went to a community college. He applied to 10 universities and got accepted in 9, but, unfortunately, I cannot help financially.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Sunnyvale, CA “She’s still interested in going to the armed forces, but what’s stopping her is wanting to help bring more money home.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Los Angeles, CA |

Increased Fear

Remaining family members became significantly more fearful and worried that others in the family could be taken at any time. Families said they are living on edge and anxious all the time. A number said they limit their driving and time outside the home as well as their interactions with people in the community. For example, one woman said she no longer goes to the market or other places where there are large numbers of Latinos because she worries that ICE will target these locations. Some stakeholders reported that families are less willing to contact the police for help and one stakeholder noted that her community has had a decline in domestic violence calls.

| “….after what happened with my husband I do not feel safe anywhere…I think that at any time they will come and arrest me, and they will take me.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Los Angeles, CA

“I don’t leave my house. No, I go from work to home, to school… We live in isolation from the world right now.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, DC Area |

Adults tried to protect children, but many children had increased fears. Some adults tried to protect children by not sharing the details of what happened to the detained or deported family member. However, children still often heard about the circumstances through siblings or other family members or heard about issues in school that made them worried. Families with older children typically had shared the details of what happened to the detained or deported family member. One respondent noted that the children witnessed their father being detained and said it was a traumatic and scarring experience. Families and stakeholders said children are scared that their remaining parent or other people in the family will be taken and often want to stay physically close to and in constant contact with them. One stakeholder said she has heard stories of children sleeping by the front door because they worry wither their parent will still be there when they wake up. Families and stakeholders also said that children fear for the safety and well-being of their detained or deported family member.

| “I didn’t tell them their dad was taken. I told them their dad had to go work there, just for a time and then he will return…” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Sunnyvale, CA

“…he’s being detained, in front of their eyes—so they’re scarred…” Adult Daughter of Detained/Deported Individual, Houston, TX “There’s fear, a lot of fear….Even kids, sometimes when they’re playing they say…‘immigration is coming!’ and they all run away.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Houston, TX |

Extreme Stress, Anxiety, and Depression

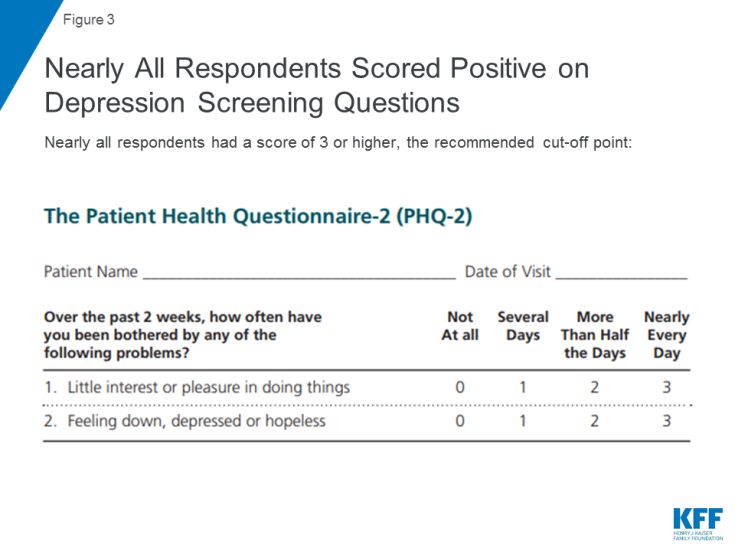

Nearly all respondents appeared to be experiencing symptoms of depression, with the majority having a positive score on a clinical depression-screening tool (Figure 3).1 Respondents described feeling extreme sadness and, in some cases, desperation. A few said they have had suicidal thoughts. Many reported problems eating and sleeping as well as stomachaches and headaches. Several said that chronic conditions like diabetes and hypertension have gotten worse due to increased stress and anxiety. While suffering internally, adults said that they try to be strong for their children and attempt to hide their worries and sadness.

| “It’s a sense of sadness for everyone, everybody, the whole family…we all feel sick, depressed. None of us has any energy.” Mother of Detained/Deported Individual, Sunnyvale, CA

“Sometimes…I’ve thought about not living anymore. I want this to be over now! But, then my kids…motivate me. Because they’re the main thing that keeps me going.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Los Angeles, CA “I don’t sleep at all. The days pass by and I don’t realize them, the days pass by—4:00 a.m. comes I am still awake.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Houston, TX “…my diabetes got a lot worse, a lot. My cholesterol and diabetes both got worse…” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, DC Area |

Children also experienced sadness, anxiety, and behavioral changes. Families and stakeholders said children are sad and anxious, crying, and frequently asking for the missing family member. They also observed problems eating and sleeping, developmental regressions, and eating disorders stemming from stress and anxiety. Several families said their children became more withdrawn and no longer socialized with friends. Teenage children felt increased stress from added responsibilities and pressures. For example, one teen said she feels a lot of pressure to do well in school while at the same time struggling with the sadness and stress of losing her older brother, who was the main breadwinner for the house.

| “…my youngest daughter is destroyed emotionally, devastated. She cries, dreams about it. She wants her dad and doesn’t have him.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, DC Area

“[My mother] tells me not to work during the school year…she tells me to only study…that’s the only thing I can do, get good grades so I won’t disappoint her.” Teenage Sister of Detained/Deported Individual, Houston, TX “…she wets the bed, and she’s 9. So, I think it’s a way of seeing what’s going on, because she never did that and now she does it often.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Los Angeles, CA “…[my granddaughter] no longer wants to play with other kids. She wants to be by herself… Before, she was never afraid…but now, she’s really isolated from everything.” Mother of Detained/Deported Individual, Sunnyvale, CA “[My grandson] can wear the same clothes for a long time and he goes to school and he doesn’t ask for anything, because he can see that his mom cannot afford it.” Mother of Detained/Deported Individual, Fresno, CA |

Stakeholders emphasized that the stress and children are experiencing today will have long-term negative effects on their physical and mental health. They pointed to research showing that stress and trauma contribute to higher rates of chronic disease and mental health issues.

| “There’s a lot of studies that indicate just the simple stress alone, the anxiety alone can, they can preclude the patient…[to] be more susceptible to chronic diseases such as hypertension and diabetes.” Health Center, TX

“And, so we focused a lot on mental health because that’s where it feels most immediate, but the physical health sequela are going to be long, long, range impacts….” Health Center, DC Area “…you can talk about them in terms of that short-term effect of the child who’s crying, but where is that child 20 years from now? And this is not the kind of trauma that sort of happens once and… it goes away. It’s the kind of trauma that lingers generationally….” Legal Services Provider, CA |

Declines in School Performance

Parents and stakeholders reported abrupt declines in children’s performance in school, which stakeholders cautioned may have long-term negative impacts on their future success. In some cases, children missed days of school due to the disruption and emotional trauma in the family. Stakeholders also reported drops in school attendance after raids within a community. Some families said their children had to change schools multiple times because they moved frequently due to unstable housing situations. Families and stakeholders said that children had more difficulty paying attention in school due to stress and worries as well as problems sleeping. They noted that teens face competing pressures to do well in school and help support their families while at the same time dealing with the trauma of losing their family member. An educator noted that, physiologically, it is more difficult for children to learn because they cannot access the correct area of their brain when they are experiencing stress and trauma. Stakeholders also emphasized that increased fear and trauma among students is affecting the broader student body and school beyond those directly affected by enforcement activities. For example, teachers are spending more time reassuring and calming students, which takes away from time spent on academics. They also stressed that children may experience long-term negative impacts on educational attainment and future success due to their declining grades and loss of hope for the future.

| “Her grades went down, and they sent her to summer school because she wasn’t doing well…because she was sleeping sometimes…at school. She’d be awake at night crying…and sometimes she’d be tired when she went to school.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, DC Area

“I noticed that my grades would go down…I get distracted because I am thinking about it at school or sometimes I don’t sleep at night because I am thinking about it and then I get sleepy at school.” Teenage Sister of Detained/Deported Individual, Houston, TX “…they’re also not learning because their brains are not even letting them learn… they’re not even able to access that frontal lobe and grow it out and mature it out. So yes, we do see developmental delays there associated with it.” Educator, DC Area “…it just creates a very bleak future for some of our young people…we’re creating such…an environment of hostility and discouragement for our students that’s basically going to affect generations to come, I mean we’re going to have students that perhaps are not interested in going to college, are not interested in furthering their education…” Educator, CA |

Gaps in Mental Health Care

Despite significant mental health needs, most families were not receiving counseling or other mental health services. Although a number of respondents expressed interest in and thought they might benefit from counseling or other mental health services, adults generally had not sought care for themselves. Most children also were going without counseling or other mental health services. Families and stakeholders pointed to several barriers to obtaining care, including the lack of coverage among adults and cultural biases against seeking mental health care within the Latino community. In addition, for many adults, meeting their basic needs was a higher priority than obtaining mental health services. Although some parents were interested in obtaining counseling for their children, in some cases, they were scared to share their family situation with their children’s doctor or clinic. Stakeholders also pointed to lack of available mental health services as a significant barrier and noted that waiting lists for care are sometimes months long. They stressed the importance of expanding the availability of culturally appropriate in-language services that can address the increasingly complex situations of families.

| “…you can’t do therapy for somebody who is just trying to figure out how they’re going to survive during the next week.” Health Center, CA

“Normally, especially in Hispanic families, it is very frowned upon or it’s a taboo for me to ask for counseling…” Teenage Sister of Detained/Deported Individual, Houston, TX “[My granddaughter] has a good doctor, but we don’t want to say much to doctors because then they start to do some kind of investigations.” Mother of Detained/Deported Individual, Sunnyvale, CA “…if I refer out, parents might…have to wait two or three months before they get the services because the slots that are available are filled.” Educator, CA |

Teachers and schools served as an important link to counseling for some families. Several families had shared information about their family situation with their child’s teacher or school after the teacher identified behavioral changes or the child shared information. In a number of cases, the schools connected the children and sometimes the parents to counseling. Stakeholders reported that schools are seeing an increased need for mental health services. They noted that teachers recognize behavioral changes among children, which then lead to conversations with the family that reveal immigration-related issues. Schools are responding to increased needs through direct counseling services and referrals to external providers, with some schools developing partnerships with local mental health departments. However, stakeholders stressed that schools do not have the capacity to meet growing needs.

| “I always had a good relationship with their teachers. I told her what was going on because my girl had told her.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Sunnyvale, CA

“…when my son found out, he started to behave badly at school…and I didn’t have a choice but to tell the teacher that this was affecting him…” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Houston, TX “…we are fortunate in the fact that we have two amazing counselors, however, they’re limited as to what they can offer…because we’re a school of 1,500 and…2 to 1,500 is the ratio.” Educator, CA |

Increased Barriers to Health Care

Some families lost their health insurance after their family member was detained or deported. In some cases, adults in the household had private coverage or Medicaid, but most were uninsured because they did not qualify for Medicaid or were fearful about enrolling in Medicaid and could not afford private coverage. Most children in the households had Medicaid coverage since many are U.S.-born and qualify for coverage. However, some were uninsured because they did not qualify or because their families were fearful of enrolling them. In several cases, the detained or deported family member had employer-sponsored insurance that covered the family. The family lost this coverage when that family member was detained or deported. Some children in these families transitioned to Medicaid, but the remaining spouse generally was not eligible and became uninsured. In one case, the employer continued the family’s coverage for six months, but the family will likely become uninsured when this coverage ends.

Families generally were continuing to obtain health care for children, but getting care became more difficult. Respondents noted that children generally were continuing to get needed health care services, including check-ups and immunizations. Families and stakeholders noted that school requirements for immunizations and well-child visits help ensure children continue to receive care. Some families said it became harder to get to doctor visits due to losses in transportation and increased work hours. Cost generally was not a barrier to care for children, since they typically had Medicaid coverage. However, some families had difficulty affording care for children who were uninsured. For example, one parent reported that she could no longer afford medical supplies or transportation to appointments for her son with disabilities. Further, one teenager was going without treatment for previously identified anemia and other health problems because her families had disenrolled her from Medicaid due to fears.

Fear of Accessing Public Programs

Many families were avoiding health, nutrition, and other programs due to fear. Families worried that participating in these programs could jeopardize the chances of having their detained or deported family member released or able to return to the U.S. They also feared it could prevent themselves from obtaining legal status or citizenship in the future. Several reported that attorneys and/or public officials had advised them not to participate in any programs or receive assistance because it could negatively affect their immigration case. As such, many families were not participating in SNAP (food stamps) or WIC, even though their U.S.-born children would likely qualify and the families were having problems affording food. A number of families continued Medicaid coverage for their children despite these worries because their children’s health care was such a high priority and they could not go without the coverage. However, a few had not enrolled their children in Medicaid or had disenrolled their children from Medicaid due to these concerns.

| “In the immigration office, they told us that if we request asylum we couldn’t get anything from the government.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Fresno, CA

“I used to get Medicaid and the food stamps, but as I wanted to get my legal status, they even say that if you ask for help from the government, you’ll be denied legal status.” Mother of Detained/Deported Individual, Houston, TX “…we’re a bit worried because my daughter has asthma. I couldn’t do it without Medi-Cal [Medicaid]. I can’t let her be without Medi-Cal [Medicaid].” Cousin of Detained/Deported Individual, Sunnyvale, CA |

Stakeholders reported declines in participation in public programs and a broader array of services due to increased fear. Consistent with what families reported, stakeholders said that their clients’ concerns about participating in public programs have increased, leading to fall offs in enrollment in food assistance programs, such as SNAP, WIC, and Free or Reduced Price Lunch, as well as Medicaid and CHIP. They also said that families are avoiding other services, including libraries and services from community organizations. One health center in Texas reported significant drop offs in Medicaid and CHIP enrollment among adults and children as well as fall offs in families seeking care through the center and following up on referrals to county hospitals. Stakeholders said that media coverage of potential changes to public charge policies are escalating these fears, even among legal permanent residents and citizens. Stakeholders have revamped and enhanced outreach efforts to assure families that it is safe for them to obtain their services and that they will protect their information, but many families remain fearful even with these assurances. Stakeholders also felt it has become more difficult for them to advise families because policies are constantly changing and they are no longer confident about what to recommend.

| “…there’s been people who are citizens who don’t want to access benefits because…as an immigrant, as a person of color there’s not the same security, even though they are citizens.” Health Center, CA

“…the Free and Reduced [Price} Lunch program is one that parents now are very afraid to provide any type of information that they feel the government might get a hold of.” Educator, CA “So I have patients who have given up their food subsidies, their assistance. They don’t go for their mammograms. I order X-rays and they’re afraid to go to the county hospital because they have to register.” Health Center, TX “…we have an emergency fund that is specifically for Latino families in the community. It doesn’t have anything to do with federal benefits, but people are afraid sometimes to access that…” Health Center, CA “…we’re worried that folks won’t approach us, or won’t try to access services because of the fear of us being connected to law enforcement or, that somehow we won’t help them because of their status.” Community Organization, TX “And always in the past, we’ve been able to be very clear and reassuring patients what is a risk and what is not a risk. But now with all of the changes…we feel insecure in terms of the information that we provide.” Health Center, CA |

Lack of Legal Help and Other Support

Many families were going without legal representation or going into debt for thousands of dollars to pay private attorneys. Respondents described many challenges finding affordable legal help for their detained or deported family member. They said that individuals receive a list of attorneys in detention, but that list is not useful. One respondent noted that she called 20 people on the list before she found one willing to help, and, even then, that help would cost thousands of dollars. Similarly, a legal services provider noted that the list in her area has not been updated in years and that it omits many providers offering pro bono services. Families said that attorneys are expensive and they are not sure which ones to trust. Many families reported that they were unable to find pro bono legal assistance and are paying thousands of dollars in attorney fees that they are covering through loans or with help from family members. Some respondents had paid large amounts to attorneys who turned out to be frauds or failed to provide the assistance they promised. Families and stakeholders also noted that families often face huge challenges paying bonds to have their family member released from detention. One legal services attorney noted that immigration bonds must be paid in full by a legal permanent resident or citizen and often range from $3,000 to $10,000, creating both logistical and financial challenges for families to pay. Legal services providers stressed that the lack of sufficient legal services leaves families vulnerable to fraud and facing huge fees for private lawyers. They emphasized that families’ ability to access legal help has significant implications, since they are much more likely to have a successful outcome when represented by a reputable and skilled attorney.

| “…there are private lawyers, and they tell you they’ll do everything for you…and then they rob you.” Mother of Detained/Deported Individual, Sunnyvale, CA

“…at first, [the lawyer] said he would charge $5,000, but later on he wanted $1,000 more, and it continued like that.” Mother of Detained/Deported Individual, Houston, TX “…a lot of people are paying really, really high fees to private lawyers….I would say between $5,000 to $10,000 dollars a person to private lawyers…and this is money that people just do not have. …they borrow from anyone they can borrow from, and then they end up with these huge debts.” Health Center, CA |

Legal services providers said it has become more challenging for them to serve families. They said that the growing number of people in detention creates challenges because more time is required to represent detained individuals. They noted that meeting with a detained client often requires a full day because the attorney must travel to the facility and often has to wait hours for space in the facility to meet with the client. One legal services provider in Texas said that many of the detention facilities are located in rural areas, which amplifies difficulties, since few attorneys are located in those areas and those in metropolitan areas have to travel long distances to meet with clients. Given these challenges, as the number of people in detention increases, attorneys must take on smaller caseloads, reducing the overall number of families they can help. Legal services providers also said that the constantly shifting policy environment makes each case more difficult and time consuming. Further, they felt it has become more challenging to obtain relief for clients and that cases are requiring more documentation and evidence.

| “…families need lawyers. I think that representation is the most urgent need to fill…you have very little chance without a lawyer in immigration proceedings.” Legal Services Provider, CA

“…without more access to legal representation, there is more space for non-attorneys like notarios or predatory attorneys who exploit our communities.” Legal Services Provider, CA “So we have an increased demand for our services, a decreased ability to provide those services because each case takes more time than it used to, which means an overall increase in the number of people who are unrepresented…” Legal Services Provider, CA “Lots of cases are getting denied. We’re getting a lot more requests for evidence…” Legal Services Provider, TX |

Families received some assistance from family, friends, and community-based organizations, but many continued to struggle to meet their basic needs. Some families received financial help from family and friends, but not all respondents had this assistance available. Churches, faith-based groups, and community organizations also were important sources of help, providing direct assistance to some families and helping to connect them to available resources. Most families learned about these resources through radio and television or word of mouth. A few employers had also been helpful to families, providing time off and, in some cases, extra financial support to the family. However, families and stakeholders noted that many families are still in need of help to meet their basic needs, particularly as they are more fearful of enrolling in public programs.

| “The only people who understand me and help me a lot with my children is my family. Financially they have helped me a lot, taking care of my daughters so I can keep working.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Sunnyvale, CA

“I have good neighbors. When my husband got deported, they supported me a lot.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Houston, TX “…an organization helped me last month to pay for one month of rent and for electricity. I never used to ask for that.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Houston, TX |

Strains on Organizations Serving Immigrant Families

Organizations and individuals serving immigrant families have experienced increased strains and challenges. Some stakeholders noted that they do not have sufficient resources to meet the growing needs among families. They have tried to enhance support available to families by deepening and expanding networks and connections to other local organizations. However, some have had to limit and refocus their priorities. Some stakeholders also made changes to their policies and operations to respond to the shifting environment. For example, health centers and some educators reported engaging in planning efforts and policy changes to better protect family information and develop procedures to respond if ICE officials were to come on premises.

| “…nowadays there’s so much, that we’re having to have deep, internal conversations to prevent ourselves from jumping on every opportunity to ensure we conserve some of our resources for other things that we foresee coming down the line…” Legal Services Provider, California

“I think the like biggest operational impact has really just been trying to train staff about what to do if there’s an ICE raid.” Health Center, CA |

Stakeholders reported increased stress and pressures among individuals serving immigrant families. Stakeholders noted that many of their staff are in mixed immigration status families and are dealing with their own family immigration issues while continuing to serve families. Stakeholders also pointed to “compassion fatigue” among individuals serving families, noting that hearing the trauma and suffering families endure takes a toll on those serving families, particularly when they feel helpless to improve the situation. As such, staff are experiencing increased stress and burnout. One organization reported bringing in mental health support for staff to try to buffer these effects.

| “Most of our staff also have a family member or a friend who is at risk for deportation, and so a lot of our team is providing care, while also trying to take care of themselves with these same levels of stressors, which makes it that much more intense for everybody because its personal.” Health Center, DC Area

“But it’s still very, very difficult…because of the level of trauma that we’re hearing, the level of suffering that people have experienced and continue to experience, is just extremely difficult to hear.” Health Center, CA “The teachers are very stressed over it and they sometimes meet with our counselors as well to help them get through it because it’s hard to see a child in crisis.” Educator, CA |

Future Plans

Families felt lost and apprehensive about their future. Many felt trapped and that they did not have any good options available. Some indicated that they plan to stay in the U.S. even if their detained or deported family member is unable to return, but were distressed about the possibility of never reuniting the family. A few were considering leaving the U.S. to be with their deported family member, but feared the violence and poverty they would experience. For a number, returning to their country of origin is not an option because they fled direct death threats and violence.

| “Here we’re discriminated against, we’re mistreated and everything else, but they’re not going to kill us…in Mexico, for a tiny thing, they’d kill you.” Mother of Detained/Deported Individual, Sunnyvale, CA

“We can’t go back to our country. …It isn’t just that they could beat you up, because they just gave me three big shoves—I did have bruises, but that was just a warning.” Spouse/Partner of Detained/Deported Individual, Houston, TX |

Stakeholders underscored the resilience of families, and remarked on their ability to continue moving forward amid their extremely difficult circumstances. They noted that despite their difficult circumstances, they continue to prioritize their children’s needs and education and work to improve their own situations. They also stressed that many families have made huge sacrifices and already overcome major obstacles to get to the U.S. with the hope of providing a better future for their children.

| “…we also are working with probably the most resilient bunch of people you could possibly ever imagine…they are dedicated to taking care of themselves and working hard in the face of almost insurmountable pressures…and they are dedicating all their resources towards making a better life for their kids.” Health Center, DC Area

“Some of these people have given everything up, they’ve cut ties with their families and everything just to get here…for this American dream.” Educator, TX |

Conclusion

Taken together, the findings show that when an individual is detained or deported, there are major cascading, effects across the family and broader community (Figure 4). These effects touch spouses/partners, children, siblings, older parents and other family members. The effects are far-reaching, impacting families’ finances, daily lives and routines, and their emotional and physical health. They also extend into the community, affecting schools, health care providers, churches and faith-based organizations, and local businesses.

Detention or deportation of a family member left families suddenly struggling to pay their bills, with many having difficulty putting food on the table. Detention or deportation of a family member often occurs suddenly and unexpectedly, leaving families in disarray and struggling to pay their bills. With the loss the detained or deported family member’s income, many families face problems paying their bills and have difficulty affording enough food as well as housing insecurity.

Families are suffering significant emotional trauma that will have lifelong negative effects on children’s health and future success. Adults and children are experiencing extreme levels of stress, anxiety, and depression. Stakeholders emphasized that the stress and trauma children are experiencing today will have long-term negative effects on their physical and mental health. They also stressed that it could limit their future educational attainment and success as adults.

Despite the significant mental health needs among families, few were receiving mental health care. The findings point to several barriers to care, including lack of coverage among adults, limited availability of providers, stigma associated with mental health care within the Latino community, and families’ fear of sharing information. Schools and teachers are playing an important role linking some families to counseling. However, stakeholders stressed that schools lack the necessary resources to meet growing needs.

At the same time needs are growing among families, they have become increasingly fearful of accessing support from public programs and other services. Although many families are facing difficulty affording food and housing, they are increasingly turning away from food and other assistance programs for which their U.S. born children would likely qualify. Draft changes that the Trump Administration has proposed to public charge policies are further escalating families’ fears of accessing programs and services, even among legal permanent residents and citizens.

There are major gaps in legal help and other support for families. Due to the lack of sufficient legal services, many families are going without representation or going into debt for thousands of dollars to pay private attorneys. Stakeholders stressed that expanding legal services available to families is a significant priority to support families at this time. Moreover, although some families received assistance through charities, churches, and community organizations, there remain significant unmet needs for financial, food, and housing assistance. These needs will likely continue to grow as families become more fearful of accessing food and health programs.

The authors also thank the Blue Shield of California Foundation for its support of the interviews conducted in California. They also extend their deep appreciation to the families and organizations who shared their time and experiences to inform this brief, as well as the numerous organizations and individuals who helped connect us to families and service providers.