State Actions to Sustain Medicaid Long-Term Services and Supports During COVID-19

Key Takeaways

States have taken a number of Medicaid policy actions to address the impact of COVID-19 on seniors and people with disabilities, many of whom rely on long-term services and supports (LTSS) to meet daily needs and are at increased risk of adverse health outcomes if infected with coronavirus. Medicaid is the primary source of coverage for LTSS, financing over half of these services in 2018. Collectively these actions could expand access to coverage (by enhancing financial and functional eligibility criteria and streamlining enrollment), expand access to long-term care services (by adding new benefits and increasing utilization limits), and bolster providers (through increased reimbursement or retainer payments). Increased funding may be required to extend community-based care more broadly and additional enrollee protections and oversight could be achieved through strengthened reporting requirements. This issue brief identifies state actions taken as of August 21, 2020 and implications for future consideration.

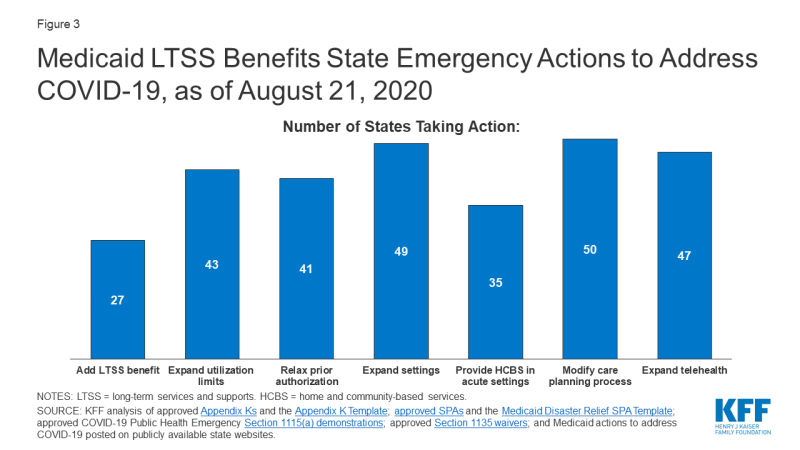

States have taken a number of emergency LTSS actions related to Medicaid eligibility, benefits and providers (Figure 1). Over half of states have expanded eligibility criteria for seniors and people with disabilities, while few states have increased the total number of HCBS waiver enrollees served. Nearly all states have streamlined enrollment processes, and over one-third of states have eased premium and/or cost-sharing requirements for seniors and people with disabilities. Just over half of states have added a new LTSS benefit to meet enrollee needs during the emergency; most benefit expansions are home and community-based services (HCBS). Most states have increased service utilization limits and relaxed prior authorization requirements. Nearly all states have increased provider payment rates for at least one LTSS and modified provider qualifications, and many have adopted retainer payments. Among states with provider payment rate increases, just over half have increased institutional rates, while about two-thirds have increased rates for at least some HCBS. Few states have required reporting on COVID-19 cases and deaths for HCBS enrollees and/or settings. CMS has adopted separate COVID-19 reporting requirements for nursing facilities.

Figure 1: Medicaid Long-Term Services and Supports State Emergency Actions in Response to COVID-19, as of August 21, 2020

The duration of the public health emergency has implications for policy actions adopted under Medicaid emergency authorities as well as the availability of enhanced federal funding provided through the matching rate increase. Many state policy changes have been adopted through temporary authorities that will expire after the public health emergency declaration ends, which will lead policymakers to assess whether any policies can or should be retained and transitioned to other authorities. In addition, some policy changes in response to the pandemic may be difficult for states to sustain without additional federal financial support beyond the 6.2 percentage point increase in federal Medicaid matching funds authorized by Congress during the public health emergency, as states are facing revenue declines and budget shortfalls.

A great deal of attention has been focused on the impact of COVID-19 in nursing homes, given the disproportionate number of cases and deaths among residents and staff nationally, with less attention on community-based residential settings. The Trump Administration has issued guidance about how nursing homes should respond to the pandemic, announced the formation of an independent commission to assess nursing home response, and adopted new reporting requirements for COVID-19 cases and deaths in nursing homes. To date, less attention to COVID-19 cases and deaths generally has been paid to community-based residential settings, such as group homes, where the pandemic presents similar risks to Medicaid enrollees and providers due to the highly transmissible nature of the coronavirus, the congregate nature of the settings, and the close contact that many workers have with residents. Data about COVID-19 cases and deaths in both institutional and community-based congregate settings may allow policymakers to more fully assess the impact across populations at increased risk of adverse health outcomes. The pandemic also may exacerbate the need for HCBS waiver services, which already are subject to waiting lists in a number of states. For example, elderly parents sickened by COVID-19 may no longer be able to provide care for their adult children with disabilities. Beyond the pandemic, the coming age wave makes LTSS and Medicaid’s role as the primary payer likely to be policy issues faced by the next Administration, in addition to the continuing effects of the pandemic and economic crisis.

Introduction

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, states have taken a number of Medicaid policy actions to address the impact on seniors and people with disabilities, many of whom rely on long-term services and supports (LTSS) to meet daily needs and are at increased risk of adverse health outcomes if infected with coronavirus. Medicaid covers nearly 7.4 million seniors and almost 11.1 million people who are eligible based on a disability as of 2014. These enrollees may be at increased risk for adverse health outcomes if infected with coronavirus due to their older age, underlying health conditions, and/or residence in congregate settings, such as nursing homes, intermediate care facilities for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities (I/DD), or group homes. In addition, many seniors and people with disabilities rely on Medicaid LTSS to meet daily self-care and independent living needs, which makes it important for their coverage and access to care to continue uninterrupted during the pandemic.

Many state policy changes related to Medicaid LTSS have been adopted through temporary authorities that, according to CMS guidance, will expire when the Health and Human Services Secretary’s COVID-19 public health emergency declaration ends. This will lead policymakers to assess whether any changes can or should be retained and transitioned to other authorities. The public health emergency declaration currently is set to expire on October 23, 2020. While some state actions have been supported by the 6.2 percentage point increase in federal Medicaid matching funds authorized by Congress during the public health emergency, policy changes may be difficult for states to sustain without additional federal financial support, given the severity and expected longevity of the economic crisis resulting from the pandemic. The amount of fiscal relief to states from the increase in federal matching funds depends on the duration of the public health emergency, while the economic consequences of the pandemic are likely to persist beyond the public health emergency period. The current increase in federal matching funds could offset or reduce state spending but is unlikely to fully offset state revenue declines and address budget shortfalls.

The election will have implications for LTSS issues, and Medicaid’s role as its primary payer, given the effects of the pandemic, the resulting economic crisis, and the coming age wave. Democratic Presidential nominee Joe Biden recently released a plan to increase access to Medicaid home and community-based services (HCBS), while the Trump Administration has proposed a Medicaid program-wide federal financing cap in the President’s FY 2020 budget and is asking the Supreme Court to invalidate the entire Affordable Care Act, including provisions that allows states to expand Medicaid HCBS. This issue brief identifies trends in state policy actions related to Medicaid for seniors and people with disabilities and LTSS as of August 21, 2020. These include actions to expand eligibility and streamline enrollment, ease premium and/or cost-sharing requirements, enhance benefits, increase provider payment, modify provider qualifications, and alter reporting requirements.

Key Findings

States are adopting Medicaid policies targeted to seniors, people with disabilities, and LTSS in response to the pandemic through a variety of authorities that have different expiration dates. These authorities include Disaster-Relief State Plan Amendments (SPAs), traditional SPAs, other administrative authorities, HCBS waiver Appendix K, Section 1115 demonstration waivers, and Section 1135 waivers. The beginning and ending dates vary by authority (Appendix Table 1).

Eligibility and Enrollment

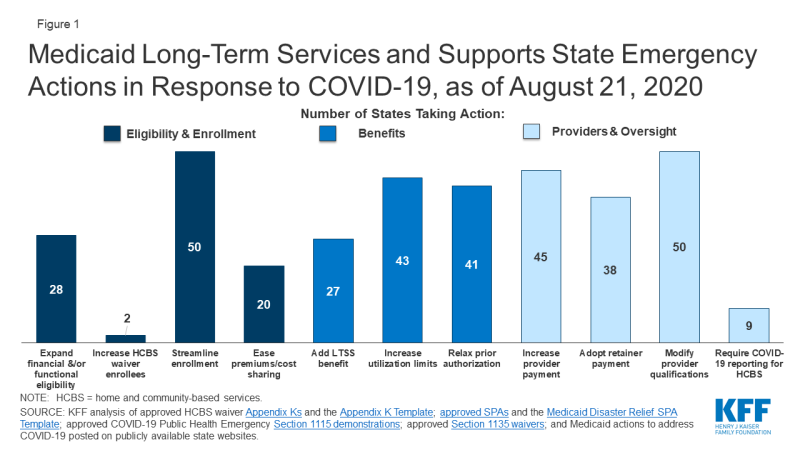

Fifteen states are expanding financial eligibility limits for seniors and people who qualify for Medicaid based on a disability to increase access to coverage during the public health emergency (Figure 2). Coverage groups where eligibility is based on old age or disability (known as “non-MAGI groups”) have income limits, and at state option, also may have asset limits. State actions to expand financial eligibility in these pathways include applying less restrictive income or asset methodologies and/or increasing HCBS waiver cost limits during the emergency period. For example, North Carolina is disregarding increases in assets for all non-MAGI groups until after the emergency period ends, and Massachusetts is allowing people with disabilities to obtain a temporary hardship waiver of the medically needy spend down requirement during the public health emergency. In addition, North Carolina and Washington are modifying financial eligibility criteria for some HCBS to cover beneficiaries who would otherwise not be eligible.

Figure 2: Medicaid LTSS Eligibility and Enrollment State Emergency Actions to Address COVID-19, as of August 21, 2020

Less than half of states (23) are expanding functional eligibility criteria to help more people qualify for coverage based on a disability during the emergency period (Figure 2). In addition to meeting financial eligibility criteria, coverage groups related to disability status require individuals to meet functional criteria, for example, based on the extent of their self-care needs. Missouri expanded coverage to adults who test positive for coronavirus by considering it a qualifying disability for its aged/blind/disabled pathway.1 Indiana is giving HCBS waiver enrollment priority to people with COVID-19 or who are presumed positive from its waiting lists for waivers that provide non-residential supports for people with I/DD, while other states are temporarily modifying HCBS waiver functional eligibility targeting criteria. In addition, 13 states are modifying HCBS waiver assessment requirements to allow individuals to begin receiving services before a functional eligibility evaluation is completed (no data shown).

Maryland and Utah are increasing the total number of individuals served in HCBS waivers during the emergency period (Figure 2). Maryland is increasing the number of individuals served in its waiver for children with autism spectrum disorder; Utah is increasing the number of individuals served by a waiver for people transitioning from institutions to the community. Unlike state plan coverage groups, states can limit the number of people who enroll in waivers, which can result in waiting lists when the number of people seeking services exceeds the number of waiver slots available. States acknowledged that the pandemic may exacerbate the need for HCBS waiver services; for example, Pennsylvania noted that many people on its waiver waiting list have aging caregivers who may not be able to continue providing care if they develop COVID-19. However, few states have been able to increase the number of waiver enrollees served in response to the pandemic. In addition, 16 states are allowing individuals to maintain HCBS waiver eligibility without receiving services, which can keep enrollees connected to coverage while services are interrupted due to provider shortages or restrictions due to state stay-at-home orders or while individuals are receiving inpatient treatment during the pandemic (Figure 2).

Nearly all states are taking at least one action to streamline eligibility determinations to expedite enrollment in coverage for seniors and people with disabilities during the emergency. Eleven states are allowing hospitals to make presumptive eligibility determinations for non-MAGI groups during the emergency, which can help connect people to coverage at the time they seek medical treatment (Figure 2). Seven states are allowing applicants in non-MAGI pathways to self-attest to financial and/or functional eligibility requirements in lieu of requiring documentation before determining eligibility (Figure 2). The most frequent action in this area is permitting virtual evaluations to determine HCBS waiver functional eligibility and/or otherwise modifying processes for HCBS waiver level of care evaluations and reevaluations to account for social distancing during the pandemic, adopted by 50 states (Figure 2).

Almost all states are extending eligibility renewal due dates during the pandemic to keep people connected to coverage and enable states to focus limited state agency staff time on responding to the emergency. Forty-nine states are extending reassessment and reevaluation due dates for one or more HCBS waivers (Figure 2). Pennsylvania is extending eligibility renewal deadlines for non-MAGI populations to every 12 months. As one of the conditions of receiving the enhanced federal matching funds under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, states must provide continuous eligibility for individuals enrolled on or after March 18, 2020 through the end of the month in which the public health emergency ends.2

Premiums and Cost-Sharing

States are eliminating or easing premiums and cost-sharing requirements to help seniors and people with disabilities remain in coverage and facilitate access to services during the pandemic. More than one-third of states are eliminating or waiving premiums in Medicaid pathways that offer buy-in coverage for working people with disabilities, while a couple of states are easing cost-sharing requirements (Figure 1). Connecticut is suspending copayments for individuals who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. Rhode Island has adopted a policy that helps ensure that people with short-term nursing home stays will have a community-based residence to which they can return post-discharge by allowing enrollees to receive a home maintenance allowance throughout the public health emergency. This policy accounts for the financial cost of maintaining a home in the community by reducing the amount that these enrollees must pay out-of-pocket for institutional care and applies to individuals who were institutionalized for less than six months as of March 1, 2020, and unable to be discharged home due to COVID-19.

Benefits

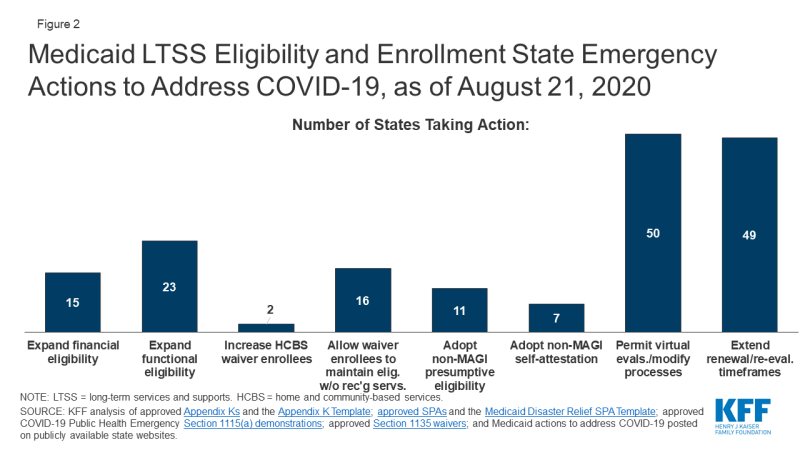

About half of states (27) are temporarily adding new services to their regular LTSS benefit packages to meet enrollee needs during the public health emergency (Figure 3). Nearly all state actions in this area relate to expanding the benefit packages available under HCBS waivers and/or Section 1915 (i) state plan HCBS. Frequently added services include home-delivered meals; medical supplies, equipment, and appliances; and assistive technology. Some states are adding other services to address the emergency. For example, Washington is adding wellness education to help HCBS waiver enrollees manage chronic conditions, avoid health risks and be informed about COVID-19. Indiana is adding rent and food reimbursement to help enrollees in an I/DD waiver offset the costs of room and board for an unrelated, live-in caregiver during the emergency. On the institutional LTSS side, Ohio has created a new benefit, Health Care Isolation Centers. These services are provided in specialized COVID-19 facilities to individuals who have been discharged from hospitals but continue to need medical and isolation care that cannot be provided in the community or their former congregate setting.

While the majority of benefits changes are expansions, one state is restricting benefits, and many are restricting visitors in HCBS settings in efforts to contain coronavirus spread (no data shown). Washington has authority to suspend specialized add-on nursing home services like habilitation during an emergency to protect the health of residents and staff. Similar to CMS guidance restricting visitors in nursing homes, 40 states are not allowing any visitors in at least some HCBS waiver residential settings to minimize the spread of infection.

Most states (43) are temporarily modifying utilization limits for covered services to ensure that enrollees can access services and address health and welfare issues during the emergency (Figure 3). Among these states, most are allowing utilization limits to be exceeded for HCBS waiver and/or state plan services. For example, Arkansas is removing its limit on physician visits in nursing homes, and Ohio is lifting hour and day limits on private duty nursing services post-discharge. In addition, 31 states are temporarily modifying the scope of HCBS waiver covered services to account for needs created by the pandemic (no data shown). For example, Tennessee is adding HCBS waiver services to support individuals with I/DD with shopping, hygiene, meal preparation and money management. By contrast, North Carolina, Rhode Island and Washington are restricting utilization of HCBS services (no data shown). All three states have Section 1115 waivers that allow them to vary the amount, duration, and scope of services based on population needs. In addition, North Carolina and Washington may target services on a less than statewide basis.

Most states (41) are suspending prior authorization requirements to ensure access to HCBS waiver and/or state plan services during the emergency (Figure 3). For example, Connecticut is waiving prior authorization for home health services, Maryland is suspending prior authorization for remote patient monitoring, and Nebraska is waiving prior authorization for transfers to post-acute long-term acute care hospitals, acute inpatient rehabilitation, or skilled nursing facility care. In addition, eight states are allowing other licensed providers to order home health services for state plan HCBS in addition to physicians (no data shown).

Nearly all states are expanding the settings where enrollees can receive HCBS to account for disruptions due to COVID-19 (Figure 3). Among these states, 49 are temporarily expanding the settings where HCBS waiver services can be provided during the public health emergency to include providing services in hotels, shelters, schools and churches, as needed. In addition, 35 states are allowing individuals in short-term inpatient settings to receive HCBS to provide communication and behavioral supports (Figure 3). Most states have adopted this policy for one or more HCBS waivers, and a couple are doing so for state plan HCBS: Alaska is allowing Community First Choice attendant care services to be provided in acute care hospitals, and Oregon is temporarily allowing payment for state plan HCBS, including home-based habilitation, behavioral habilitation, and psychosocial rehabilitation services, to individuals in an inpatient setting.

Nearly all states (50) are modifying care-planning processes to accommodate social distancing and facilitate access to services during the emergency (Figure 3). Examples of frequently adopted policy changes in this area include modifying the person-centered plan development process for HCBS waiver services, adjusting functional assessment requirements used to determine service levels, and adding electronic document signing. Other policy changes in this area include allowing verbal consent instead of a written signature for HCBS service plans and allowing the face-to-face encounter for home health services to take place up to one year after an individual begins receiving services. North Carolina and Washington are allowing for the provision of LTSS to individuals impacted by the emergency even if the services are not updated timely in the care plan. Michigan is extending service authorizations in person-centered service plans for state plan HCBS throughout the duration of the public health emergency.

Nearly all states have expanded the delivery of HCBS via telehealth (Figure 3). Forty-seven states are adding electronic service delivery methods to continue providing HCBS waiver and state plan in-home services remotely. Minnesota is allowing state plan group therapy and rehabilitative services to be provided via telehealth. Oregon is allowing adding telehealth delivery of state plan home-based habilitation, behavioral habilitation, and psychosocial rehabilitation services. Connecticut is allowing for telephonic check-ins in lieu of face-to-face assistance for certain mental health HCBS waiver enrollees. DC is also covering services provided remotely to state plan HCBS recipients, such as wellness checks and therapeutic activities.

Provider Payment

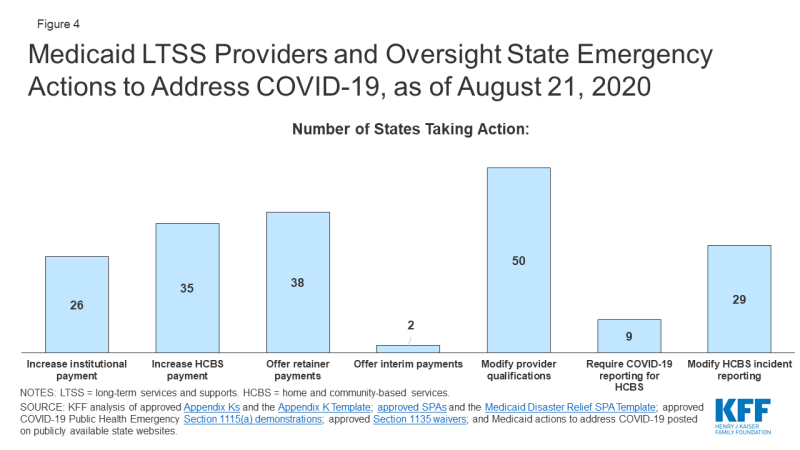

Just over half of states are increasing institutional LTSS payment rates (Figure 4). Among these 26 states, 24 have increased rates for nursing homes, which have been disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, and five states are doing so for intermediate care facilities for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities or other institutional settings (no data shown). Most states are implementing per diem or percentage rate increases, while a few states are increasing the number of days for which facilities can receive bed hold payments to account for absences due to COVID-19 treatment. Alabama also is providing an additional add-on cleaning fee. Kentucky is temporarily pausing per diem rate sanctions to nursing facilities that are unable to meet medical record review thresholds to validate assignment of patients to reimbursement groups based on acuity during the public health emergency.

Figure 4: Medicaid LTSS Providers and Oversight State Emergency Actions to Address COVID-19, as of August 21, 2020

Some states limit the additional payments to facilities or patients with a COVID-19 diagnosis, while others apply them to all nursing facilities to account for increased costs related to staffing, equipment and cleaning as a result of the emergency (no data shown). For example, Michigan is providing a $5,000 per bed supplemental payment in the first month for COVID-19 regional hub nursing facilities to address immediate infrastructure and staffing needs and a $200 per diem rate increase in subsequent months to account for the higher costs of caring for COVID-19 patients.

A couple of states specifically have included pay increases for direct care workers in nursing homes and/or other institutional settings (no data shown). Arkansas adopted temporary supplemental payments that increase direct care workers’ weekly pay by a base supplemental payment according to number of hours worked and an additional tiered acuity payment for those working in facilities with COVID-19 positive patients. Texas’ nursing facility payment rates increase includes a pay increase for direct care workers and an increase for supply and dietary costs.

Just over two-thirds of states (35) are increasing provider payment rates for at least some HCBS state plan or waiver services during the public health emergency (Figure 4). For example, Alabama is increasing waiver payment rates for personal care, adult companion, respite, and skilled nursing care to account for overtime pay, staffing needs and infection control supplies. Louisiana has received approval to increase payments for all services provided under its Community Choices Waiver for elderly and disabled adults by up to 50% as needed to maintain staffing. States increasing payment rates for HCBS provided under state plan authority include targeted case management (AK), day habilitation (AR), skilled and/or private duty nursing (DC, OK), and home health and adult care homes (NC). Arkansas’s temporary supplemental payments for direct care workers in nursing facilities also apply to direct care workers in assisted living facilities and those providing home health and personal care services in the community. Michigan adopted a supplemental payment for providers of personal care and behavioral health treatment technician in-person services. Washington’s Section 1115 demonstration waiver allows the state to increase rates for Community First Choice attendant care services by up to 50 percent to maintain provider capacity during the public health emergency. In addition, Tennessee has adopted temporary payment rate increases for community-based residential, personal care, attendant care, personal assistance and intensive behavioral treatment stabilization and treatment services and a temporary per diem add-on to community-based residential and personal care payment rates to account for direct support staff hazard pay, overtime, and PPE costs using its existing directed payment authority; these services are provided under a Section 1115 HCBS waiver.

Among the states adopting LTSS provider payment increases, 18 states have increased rates for both institutional and community-based services (no data shown). Ten states have increased provider payments for only institutional services, while 17 states have increased rates for HCBS only.

About three-quarters of states are adopting retainer payments for HCBS providers (Figure 4). Thirty-eight states have adopted retainer payments for providers offering HCBS through waiver and/or state plan authorities. For example, Washington and New Hampshire have an approved Section 1115 waiver that authorizes retainer payments for personal care and habilitation services provided under state plan authority.

Two states are making interim payments to LTSS providers (Figure 4). Among these states, North Carolina allows any Medicaid-enrolled provider to request that their reimbursement be converted to an interim payment methodology, while Georgia is making interim payments to skilled nursing facilities.

Provider Qualifications

Nearly all states (50) are temporarily modifying HCBS state plan and/or waiver provider qualifications in response to potential staff shortages and increased demand due to COVID-19 (Figure 4). Frequently adopted policies in this area include temporarily permitting payment for HCBS waiver services rendered by family caregivers or other legally responsible relatives during the emergency (if not already permitted in the waiver), adopted by 38 states (no data shown). Twenty-three states are waiving conflict of interest rules and allowing case management entities to also be direct service providers for HCBS waiver enrollees during the emergency (no data shown). In addition, all states have adopted modified provider screening requirements through Section 1135 waiver authority, which may apply to LTSS providers as well as other providers.

Reporting and Oversight

Few states are adopting reporting requirements for COVID-19 cases and deaths among HCBS enrollees (Figure 4). CMS is requiring all nursing facilities to report COVID-19 cases and deaths as of May 8, 2020, but just nine states are requiring reporting of COVID-19 cases among HCBS waiver enrollees. HCBS waiver enrollees living in congregate settings such as group homes are likely to experience increased risk from coronavirus infection similar to individuals in nursing homes. In addition to the CMS nursing home reporting requirements, three states (AZ, CT, IN) have adopted their own reporting requirements related to COVID-19 cases and deaths for long-term care facilities. For example, Connecticut requires managed residential communities and nursing homes to provide daily COVID-19 status reports. Arizona also requires reporting on COVID-19 cases and deaths from group homes.

Twenty-nine states are temporarily modifying HCBS waiver incident reporting requirements and other participant safeguards during the public health emergency (Figure 4). This allows states to focus their administrative efforts on the COVID-19 response. However, there are potential risks for enrollees as incident reporting is a requirement for HCBS programs to protect enrollees from abuse, neglect and injury and to ensure their health and safety. Twenty-eight states are delaying submitting HCBS waiver enrollment and spending reports to CMS and/or are suspending data collection for performance measures other than health and welfare (no data shown). In addition, forty-seven states are suspending pre-admission screening and annual resident review requirements for nursing facilities (no data shown).

Looking Ahead

The duration of the public health emergency has implications for policy actions adopted under Medicaid emergency authorities as well as the availability of enhanced federal funding provided through the match rate increase. Many state policy changes have been adopted through temporary authorities that will expire after the public health emergency declaration ends, which will lead policymakers to assess whether any policies can or should be retained and transitioned to other authorities. In addition, some policy changes in response to the pandemic may be difficult for states to sustain without additional federal financial support beyond the 6.2 percentage point increase in federal Medicaid matching funds authorized by Congress during the public health emergency, as states are facing revenue declines and budget shortfalls.

A great deal of attention has been focused on the impact of COVID-19 in nursing homes, given the disproportionate number of cases and deaths among residents and staff nationally with less attention on community-based residential settings. The Trump Administration has issued guidance about how nursing homes should respond to the pandemic, announced the formation of an independent commission to assess nursing home response, and adopted new reporting requirements for COVID-19 cases and deaths in nursing homes. To date, less attention to COVID-19 cases and deaths generally has been paid to community-based residential settings, such as group homes, where the pandemic presents similar risks to Medicaid enrollees and providers due to the highly transmissible nature of the coronavirus, the congregate nature of the setting, and the close contact that many workers have with residents. Data about COVID-19 cases and deaths in both institutional and community-based congregate settings may allow policymakers to more fully assess the impact across populations at increased risk of adverse health outcomes. The pandemic also may exacerbate the need for HCBS waiver services, which already are subject to waiting lists in a number of states. For example, elderly parents sickened by COVID-19 may no longer be able to provide care for their adult children with disabilities. Beyond the pandemic, the coming age wave makes LTSS and Medicaid’s role as the primary payer likely to be policy issues faced by the next Administration, in addition to the continuing effects of the pandemic and economic crisis.