No Easy Choices: 5 Options to Respond to Per Capita Caps

Congress is debating the American Health Care Act (AHCA) that would end the enhanced matching funds for the ACA Medicaid expansion and would also end the program-wide guarantee for federal Medicaid matching dollars by setting a limit on federal funding through a block grant or per capita cap. Under a block grant, federal spending would be limited to a pre-set amount. States could cap enrollment or impose waiting lists as mechanisms to control costs. Under a per capita cap, per enrollee spending would be capped, but the total amount of federal dollars to states could vary with enrollment changes and states would not be able to impose enrollment caps. Faced with restrictions in federal financing, states would have to make hard choices. Research shows that there is not strong evidence to support large savings through options aimed at achieving Medicaid efficiencies. Under a block grant, states could cap or limit enrollment; however, the incentives and options under a per capita cap could be different. This brief outlines the key measures states could use to manage their budgets and the associated challenges under a per capita cap:

- States Can Raise Taxes or Make Other Budget Cuts. Faced with reductions in federal Medicaid funding to maintain services, states could choose to increase taxes or cut other areas of their budget to fill these gaps. (Figure 1)

What are the challenges? Some states have low per capita incomes and therefore more limited tax base. While increasing taxes is not popular in any state, states with low taxing capacity could face bigger challenges. Education generally accounts for the largest share of state spending so it would be difficult to reduce state spending and exclude education from cuts. Raising revenue or reducing spending could be even more challenging given current trends that show nearly half of all states are reporting revenues coming in below projections leading to projected budget shortfalls.

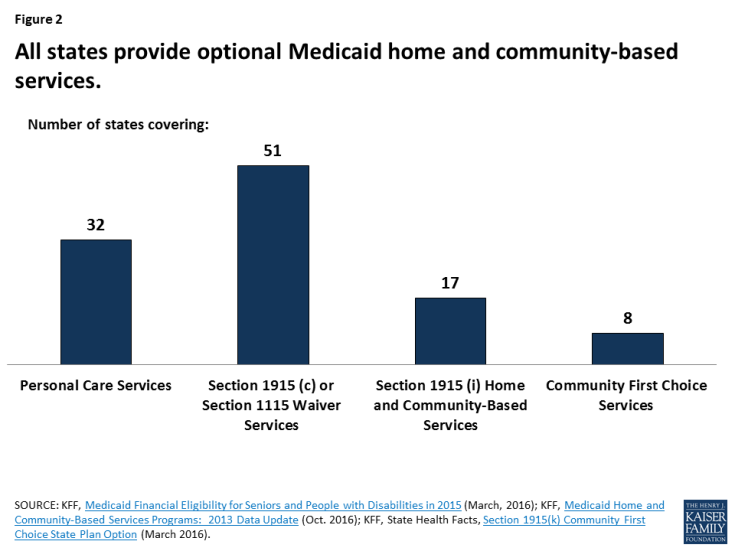

- Reduce Benefits Not Required by Statute. One mechanism to reduce per enrollee costs would be to restrict covered benefits. States could eliminate, restrict the scope or impose new or tighter utilization controls for “optional” services (those not required by statute). All states offer some optional services, including prescription drugs. Adult dental or chiropractic services are key examples of benefits that some states have restricted or eliminated during economic downturns. Nearly all home and community based long-term care services (HCBS) are also an optional service. (Figure 2) Over the last 2 decades, state spending for long-term care has moved from institutional care to home and community based settings. HCBS accounted for over half of long-term care spending by 2013. With restrictions on federal financing, an aging population and statutory requirements to cover nursing home care, states’ ability to invest in HCBS could be strained.

What are the challenges? States with limited benefits or those that have not transitioned from institutional to HCBS long-term care could be locked into those historic patterns. In addition, while restricting benefits may result in short-term savings, individuals could go without needed care and wind up with more costly problems. For example, enrollees without access to needed HCBS might wind up in nursing homes or might go without services and then develop acute care problems, such as pressure ulcers or other potentially avoidable complications. In addition, states that do not have adequate funding for HCBS may be at risk of not meeting their community integration obligations under the Supreme Court’s Olmstead decision. While Olmstead is based on the Americans with Disabilities Act and does not change or interpret federal Medicaid law, the Medicaid program plays a key role in community integration as the major payer for long-term services and supports, including the HCBS on which people with disabilities rely to live independently in the community.

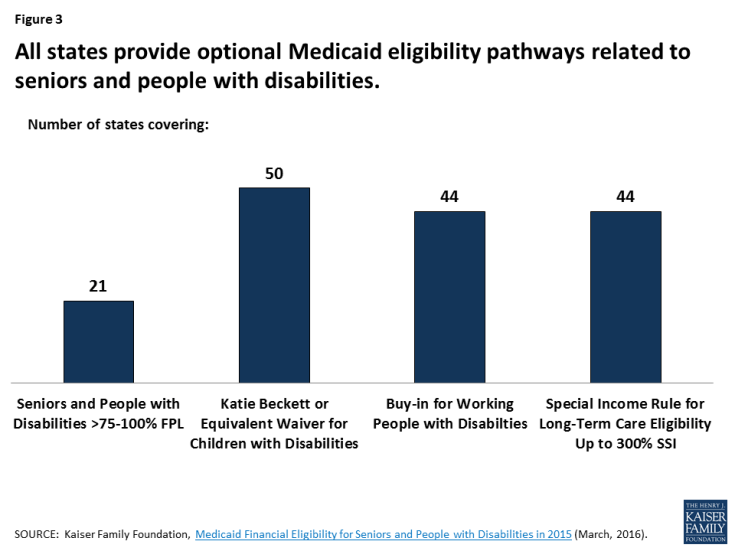

- Limit Coverage of High Cost Enrollees. A per capita cap would provide states with an allowance per enrollee for each enrollment group. States would have an incentive to eliminate coverage for high cost enrollee groups and maximize enrollment for the lower cost enrollees within each group. Most aged and disability-related coverage pathways are provided at state option, making them subject to potential cuts if states are faced with federal funding reductions. (Figure 3). Optional eligibility pathways that cover particularly high cost enrollees could be most at risk. People with disabilities covered by Medicaid include people with physical disabilities, such as cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, and traumatic brain or spinal cord injuries; intellectual or developmental disabilities (I/DD), such as Down syndrome and autism; and mental illness. Medicaid plays an important role by providing health insurance coverage for more than one in three nonelderly adults with disabilities.

What are the challenges? If the federal financing in the per capita caps is not sufficient to cover the costs for the elderly and people with disabilities, states could seek to eliminate optional pathways or tighten eligibility rules. Without Medicaid, many individuals covered under these pathways would not have access to needed care and services. Many services are not covered by private insurance and extremely expensive to obtain paying out of pocket. Medicaid and CHIP currently cover 44% of all children with special health care needs including children with Down syndrome, cerebral palsy, and autism.

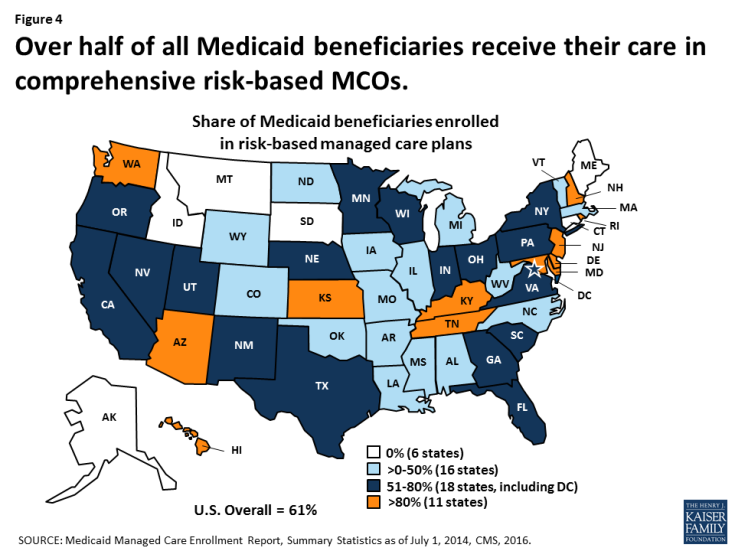

- Reduce Provider Rates or Implement Delivery System Reforms. During recessions and economic downturns, states often turn to provider rate cuts to achieve budget savings. States tend to increase or restore rate cuts when the economy improves. For many years, states have also been moving to managed care delivery systems to both improve care and control costs. (Figure 4) States could turn to these options to lower costs under a per capita cap.

What are the challenges? Reimbursement rates for Medicaid are generally lower than private insurance, so cutting rates could restrict access to care. While states may achieve some savings as they transition to managed care, most states have already made this transition. Other more complex delivery system reforms such as integrating physical and behavioral health may produce longer term efficiencies but often require upfront investments that would hard to make with capped financing.

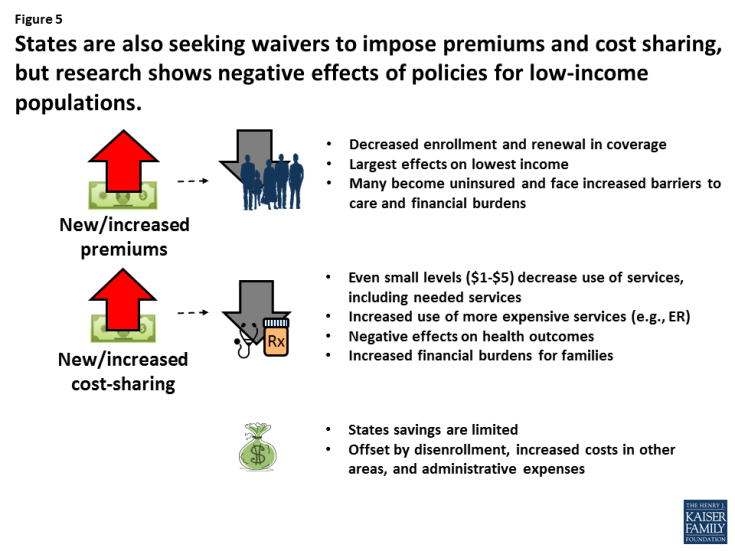

- Implement Policies to Promote Personal Responsibility or Skin in the Game. Imposing more personal responsibility for beneficiaries by imposing work requirements, premiums or cost sharing or healthy behavior incentives are often ideas discussed in conjunction with capped financing. (Figure 5)

What are the challenges? A large body of research shows that premiums and cost-sharing requirements result in coverage losses and reduced utilization which can generate some cost savings due to lower enrollment or suppressed utilization. (Figure 4) Work requirements are also under consideration; however, these policies may apply to a small share of enrollees as about 6 in 10 adult Medicaid enrollees already are working and those not working report significant barriers such as illness, disability or care-taker responsibilities. While some states are testing healthy behavior incentives, participation has been low and it seems clear these policies would not generate significant savings. Studies also point to high administrative costs and the need for sophisticated systems to implement and track these policies.

Looking ahead, this brief outlined some options for states to consider if faced with limited federal Medicaid funding under a per capita cap. However, caps do not account for future spending increases due to new drug therapies or other medical advances for which Medicaid spending would not keep pace. Given that it is unlikely that states will be able to fill gaps that result from a substantial loss of federal Medicaid funds through increased taxes, decreased spending in other state budget areas, or greater efficiencies within Medicaid, the effect of a per capita cap would be Medicaid cuts in the form of lower payment rates, fewer benefits and restricted eligibility.