Beyond the Numbers: Access to Reproductive Health Care for Low-Income Women in Five Communities

Dallas County (Selma), AL

KFF: Usha Ranji, Michelle Long, and Alina Salganicoff

Health Management Associates: Carrie Rosenzweig and Sharon Silow-Carroll

Introduction

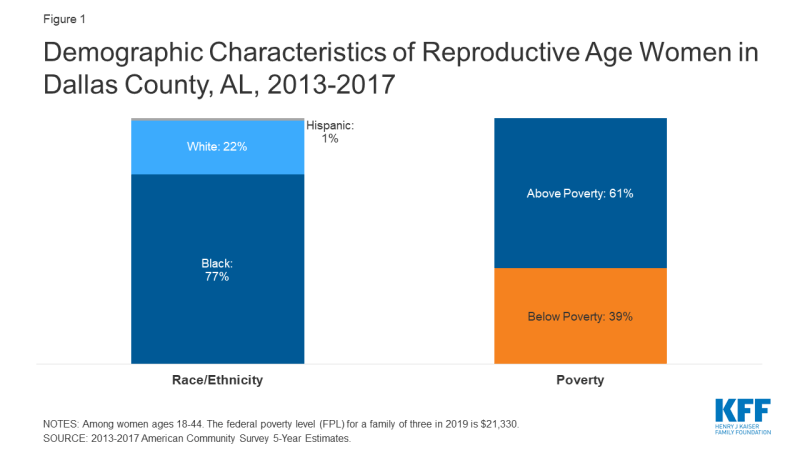

Dallas County is one of 18 counties comprising the largely rural, agricultural Black Belt region of Alabama. Originally a reference to the region’s dark, fertile soil, the term Black Belt later became associated with African American enslavement on plantations, and more recently with its majority African American population (Figure 1).

Dallas County is one of 18 counties comprising the largely rural, agricultural Black Belt region of Alabama. Originally a reference to the region’s dark, fertile soil, the term Black Belt later became associated with African American enslavement on plantations, and more recently with its majority African American population (Figure 1).

Selma, the largest town in Dallas County, played a pivotal role in the Civil Rights Movement. While considered the “Queen City of the Black Belt,” Selma faces high poverty and unemployment rates and poor health outcomes. Dallas County is federally designated as medically underserved and as a health professional shortage area. Alabama’s decision not to expand Medicaid, coupled with the state’s extremely low Medicaid income eligibility limits (18% of the federal poverty level for parents), leaves many low-income residents without access to coverage for basic health care services. Approximately 20% of Dallas County residents age 19-64 were uninsured in 2017.1 Several community hospitals have closed in recent years, leaving one hospital in Selma with the only obstetric delivery services in the seven-county region. Alabama has recently been thrust into the national spotlight with its passage of a near-total abortion ban, punishable by up to 99 years in prison for the provider. This law has been blocked by a federal court ruling, but it is expected that the state will continue to challenge it. Churches are central pillars of community life, and many have strict beliefs about sex and reproductive health and tend to oppose abortion.

This case study examines access to reproductive health services for low-income women in Selma and Dallas County, Alabama. It is based on semi-structured interviews conducted by staff of KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA) with safety net clinicians and clinic directors, social service and community-based organizations, researchers, and health care advocates (“interviewees”), as well as a focus group with low-income women in April 2019. Interviewees were asked about a wide range of topics that shape access to and use of reproductive health care services in their community, including availability of family planning and obstetrical services, provider supply and distribution, scope of sex education, abortion restrictions, and the impact of state and federal health financing and coverage policies locally. An Executive Summary and detailed project methodology are available at https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/report/beyond-the-numbers-access-to-reproductive-health-care-for-low-income-women-in-five-communities.

| Key Findings from Case Study Interviews and Focus Group of Low-Income Women |

|

Medicaid Coverage and Continuity

Alabama’s decision not to expand Medicaid and its low Medicaid reimbursement rates and income eligibility limit leave many low-income residents without health care coverage for most basic health care services outside of pregnancy (Table 1). As a result, low-income women rely heavily on the state’s family planning waiver program (Plan First), the federal Title X family planning program, and some targeted, limited public programs.

| Table 1: Alabama Medicaid Eligibility Policies and Income Limits | |

| Medicaid Expansion | No |

| Medicaid Family Planning Program Eligibility | 146% FPL |

| Medicaid Income Eligibility for Adults, Without Children 2019 | 0% FPL |

| Medicaid Income Eligibility for Pregnant Women, 2019 | 146% FPL |

| Medicaid Income Eligibility for Parents, 2019 | 18% FPL |

| NOTE: The federal poverty level for a family of three in 2019 is $21,330. SOURCE: KFF State Health Facts, Medicaid and CHIP Indicators. |

|

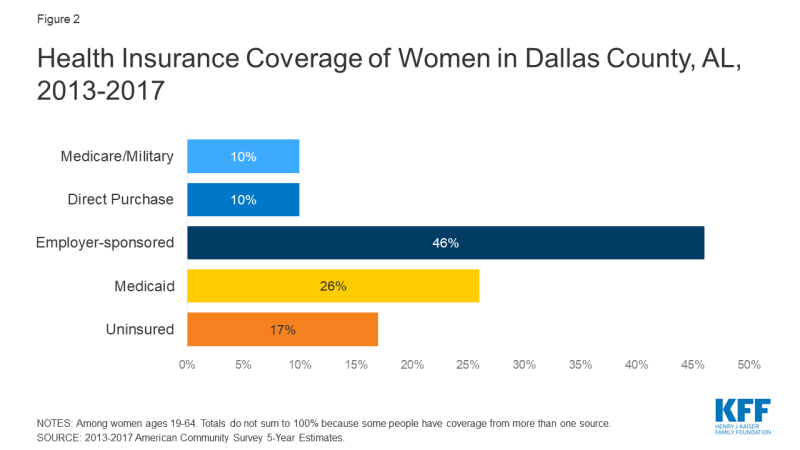

The vast majority of low-income women in Alabama do not have a pathway to basic health coverage outside of pregnancy-related coverage under Medicaid. Alabama has not expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, and women with dependent children who earn more than 18% of the federal poverty level (FPL), or roughly $3,800 a year for a family of three, exceed the state’s eligibility threshold, which is the second lowest in the United States. Adults without children at any income level who are not pregnant are not eligible. Pregnant woman are eligible for Medicaid up to 146% FPL, though that coverage ends 60 days after delivery. Several interviewees mentioned lack of Medicaid expansion as a significant barrier to accessing care. One focus group participant said that she lost her Medicaid coverage and became uninsured after her husband started collecting Social Security checks. Few low-income focus group participants had full-benefit Medicaid, while many more only had coverage for family planning (Figure 2).

The Dallas County Health Department participates in the Well Woman Alabama program, offering free health counseling, preventative services, screenings, and management of chronic diseases such as elevated cholesterol and hypertension for women ages 15-55. A Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) in Selma provides health services to uninsured women on a sliding fee scale; however, many focus group participants reported that when they need health care, they go to the emergency room where they do not need to pay anything upfront.

“The lack of expansion of Medicaid is the single greatest factor [affecting access to family planning services] beyond a shadow of a doubt.”

–Felecia Lucky, President, Black Belt Community Foundation (BBCF)“Pregnant women also need services for after their pregnancies. The women in the Black Belt need dental and vision services, education about what happens after pregnancy…education about lactation. The focus is all on pregnancy and not what the woman needs afterwards. If Medicaid could even cover 12 months after [delivery], she could focus on herself.”

–Keshee Dozier-Smith, CEO, Rural Health Medical Program (RHMP)

Alabama’s family planning program, Plan First, is often the only source of contraceptive coverage for low-income women. The Plan First2 program covers all FDA-approved contraceptive methods, STI and HIV testing, and an annual exam at no cost for women ages 19-55 with income up to 146% FPL. The program also covers tubal ligations and vasectomies for adults 21 and older. In Dallas County, the only providers participating in Plan First are located in Selma. This reportedly poses a barrier to women who live in the outlying areas of the county because there is no public transit infrastructure, and many low-income families do not own cars. Because women who have undergone sterilization are not eligible for the program, some focus group participants reported that they lost access to needed services after they had a tubal ligation or hysterectomy. Interviewees recognized the important role that the Plan First program plays to fill gaps in women’s health services, but felt that expanding full-benefit Medicaid would go much farther in meeting the health needs and providing continuity of care for Alabama’s low-income residents.

“There are women in my state who only have coverage when they are children, pregnant, or turn 65. If we’re serious about saving lives, we would not let so many women of childbearing age to fall into the Medicaid gap.”

–Terri Sewell, U.S. Rep. (AL-07)

Provider Distribution

Because there is only one remaining hospital offering Ob-Gyn and labor and delivery services across much of central and southern Alabama, many women must travel long distances for maternity care and have limited options. Some providers are developing innovative solutions to address transportation difficulties, provider shortages, and health care system fragmentation.

Dallas County has a shortage of obstetric providers, and both focus group participants and interviewees expressed concerns about the quality of care available due to challenges in recruiting and retaining physicians. Providers in Dallas County, one of the poorest counties in the state, reported that it is hard to recruit qualified employees — from front desk staff to physicians — because many people living in the area do not have the required education or work experience, and those who are qualified leave for better opportunities elsewhere. Interviewees reported that the number of Ob-Gyns providing the full range of obstetric and gynecological services in the region has declined to just two, both of whom are employed by the Selma hospital’s outpatient obstetric clinic. Focus group participants and interviewees expressed concerns about the limited choice of providers and quality of care as a result of these shortages. Individuals needing specialty care must travel to Birmingham (90 miles) or Montgomery (50 miles).

“After my third baby I wanted my tubes tied. But they wouldn’t tie them the day I delivered; they wanted me to come back in 30 days. I had already signed my papers…and I was like I’m not going to deliver this baby, get healed up and wait 30 days to go back through this pain. And so, I ended up pregnant again .”

-Focus group participant

Hospital closures throughout the state have left only one community hospital serving five counties, and the only hospital with inpatient labor and delivery services in a seven-county region. The lack of Medicaid expansion and low reimbursement rates were mentioned by providers and other interviewees as contributing factors to hospital closures in smaller towns across southern and central Alabama. As a result, Selma’s community hospital (Vaughan Regional Medical Center) has become the main place people go for health care, and the only site for inpatient labor and delivery services and outpatient obstetric care in the entire region. In addition, there is no Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) or pediatric surgery unit in Dallas County; newborn infants needing emergency care must be taken by helicopter to facilities in Birmingham. One interviewee commented on the high rates of infant and maternal mortality in the area and said that the lack of Medicaid expansion, education, and providers have all played a role.

“[The only two OB doctors in Dallas County are] doing deliveries all day, so they don’t [likely] have time to do…family planning…. Most of the doctors in our counties are internal medicine doctors. The local health departments currently have limited resources to offer family planning services, and their focus across the Black Belt is chronic care management. Heart, kidney, obesity, and diabetes are the primary diseases.”

–Keshee Dozier-Smith, CEO, RHMP

Telemedicine is emerging as a promising solution to address the transportation and distance barriers in Dallas County. There is no public transit infrastructure in Dallas County and women in outlying parts of the county must travel long distances to access health care, impeding access to all health care services. Although West Alabama Public Transportation, a Medicaid transportation program, is an option, individuals reported that they may have to wait all day to be picked up to return home. Many interviewees and focus group participants reported having to pay their family or friends as much as $20 for a ride to get health services.

Because of transportation barriers and difficulties recruiting clinical staff, several providers are implementing highly sophisticated and successful telemedicine networks. Medical Advocacy and Outreach (MAO) is a Montgomery-based health and wellness service provider serving nearly 2,000 people living with HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis C, and other life-threatening illnesses annually across 28 counties; they have established one of the only telemedicine networks that provides direct medical care in the region. As of April 2019, they had 10 units installed, with a goal to put a telemedicine unit in every county health department. Their local AIDS services partner in Selma, Selma AIDS Information and Referral (AIR), also offers videoconferencing for substance use and mental health counseling. Nonetheless, a lack of broadband throughout the most rural parts of the county limits the utilization of digital health solutions and emphasizes the importance of both transit and communications infrastructure development in rural communities. The Rural Health Medical Program (RHMP), the only FQHC in the county, offers medical consultations across sites between nurse practitioners and collaborating physicians and with partnering specialists. RMHP also has a telepsychiatry program, and they are renovating a mobile van they expect to be operational in fall 2019 that will offer medical care, optometry, as well as behavioral and mental health services in satellite towns, school-based programs, and community health fairs.

“In a lot of rural counties, they weren’t talking about HIV care. Now they are [with telemedicine]. They know that services are available and nearby.”

–Medical Advocacy and Outreach (MAO) staff

The health care delivery system in Selma and Dallas County is significantly fragmented, and providers face challenges with care coordination. Low-income women generally go to the health department for family planning needs and STI care, the hospital and outpatient clinic for obstetrical care, and the RHMP or the emergency room for all other services. One provider felt that although the system was fragmented, providers communicate with one another and patients know where they need to go for each service. The RHMP, however, is trying to integrate care with other providers and centralize services for their patients. They explained that the fragmentation of the health care system places pressure on social workers, who are scarce in Selma, to coordinate and direct patients to care.

| Initiative: Integration of health care services |

| The Rural Health Medical Program (RHMP) is Dallas County’s only Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC), with eight health centers across six counties. They are a key provider for low-income individuals in the area, serving roughly 7,800 patients annually, 40% of whom are covered by Medicaid, 35% by Medicare or private insurance, and 35% uninsured. They offer a wide range of health care services on a sliding fee scale, and recently received grant funding for behavioral, mental, and oral health expansion. They also recently became a Plan First provider and are working to build up their family planning service line, including a social worker for family planning. To reduce fragmentation within the local provider network, they have established a “memorandum of understanding” with Selma’s hospital (Vaughan Memorial Regional Hospital) and are working on establishing these partnerships with other providers in the area to support and enhance referral relationships. |

There is a severe mental health provider shortage, and many focus group participants reported experiencing stress, anxiety, and depression. Focus group participants described significant stress related to finances, family, and health. A few had seen a doctor and were taking medication for their depression and anxiety, but they felt that the medications’ side effects often made them unable to take care of their children or perform daily activities. Some local providers have expanded their mental health programs, but an interviewee still noted a significant shortage in mental health providers.

STI and HIV Screening, Prevention, and Treatment

There are not enough providers distributed around the county to meet the need for STI testing and treatment. Alabama has some of the highest STI rates in the nation, and the Black Belt region is especially hard hit. The Dallas County Health Department offers free testing, treatment, and annual screening for all STIs, HPV vaccines, and discusses HIV and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with their patients. They also employ an HIV coordinator, and their disease control staff does extensive education and outreach in colleges and churches. Still, people in the outskirts have difficulty getting to the health department.

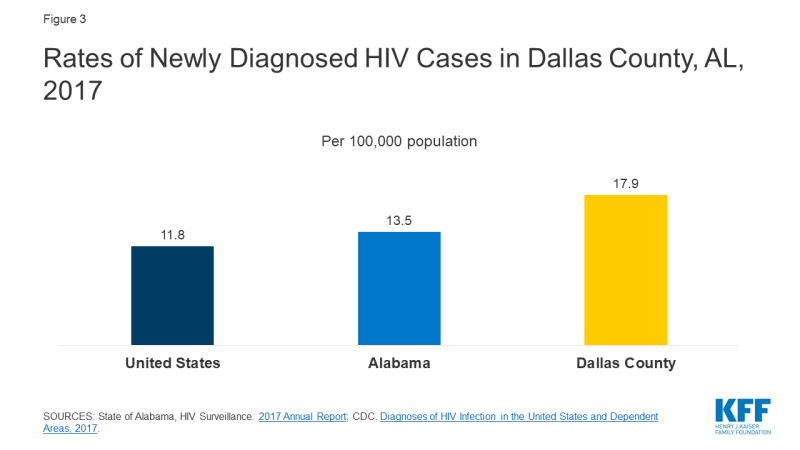

Dallas County has a comprehensive, integrated provider network for individuals diagnosed with HIV, but there are not enough providers conducting routine HIV screening, testing, or prevention. In 2017, Dallas County had a new HIV diagnosis rate of 17.9 per 100,000 people (compared to 11.8 nationwide), one of the highest in the state (Figure 3). Interviewees reported that HIV disproportionately affects young African American men who have sex with men. MAO serves as a “one-stop shop” for individuals diagnosed with HIV, providing HIV treatment and comprehensive health care services. Selma AIR conducts HIV testing and refers patients who test positive to the MAO satellite clinic housed at UAB Selma Family Medicine for treatment.

However, updates in testing policies have not yet been fully adopted by many individual clinicians. For example, MAO has been educating hospital administrators about the removal of a requirement for a separate consent for HIV testing, but the change in practice has not yet been implemented at all levels of the system. The hospital’s outpatient obstetric clinic routinely tests for HIV, but interviewees suggested that other doctors are not discussing HIV risks with patients due, in part, to competing priorities like the high burden of chronic diseases, and the continued stigma around HIV.

Interviewees reported there is limited funding for HIV prevention efforts. Although PrEP is a highly effective preventive medication for HIV and is available free of cost for lower-income individuals through an assistance program from the manufacturer, that option does not appear to be fully leveraged. In fact, interviewees reported that most of their patients hit roadblocks because they lack health insurance to cover PrEP.

Stigma and confidentiality concerns were cited as significant barriers to HIV testing and treatment. Interviewees discussed local resistance to HIV testing due to homophobia and assumptions about “what someone with HIV looks like.” They also suggested that some providers in private practice do not want to care for patients with HIV. Additionally, there is a lack of awareness among some providers that women living with HIV can give birth without transmitting it to her infant.

Because Selma is a small community, there is also concern about confidentiality. Selma AIR provides transportation to appointments, but they reported that they have patients who do not want to be seen in their van or in a clinic known to be associated with AIDS, and some have stopped coming in for medical services due to a fear of encountering someone they know.

“Stigma [related to HIV] is alive and well.”

–MAO staff

| Initiative: Comprehensive, integrated care for people living with HIV |

| Medical Advocacy and Outreach (MAO) is a non-profit health and wellness organization that provides clinical HIV care and social services, funded in part by grants from the federal Ryan White HIV/AIDS program. MAO has three full-service clinics and 10 rural e-health satellite clinics that “meet their patients where they are” through telemedicine. Their telemedicine network uses Bluetooth-enabled devices such as stethoscopes and dermascopes, which expands their capacity to serve more patients and get patients into care faster. Often serving as an individual’s only provider, MAO offers their clients living with HIV primary and preventive care, including routine STI testing, dental care, mental health and substance use treatment, PrEP and an in-house pharmacy where patients can access medication regardless of income. MAO also operates a food bank and used clothing closet and provides transportation for medical visits. MAO has a clinic for pregnant women with HIV to help minimize the risk of perinatal transmission. Since starting this clinic, there have been no cases of maternal-fetal HIV transmission. Their family planning clinic offers pregnancy testing, counseling, Depo Provera, the pill, patch, and a direct referral to a private physician for IUDs. MAO can also prescribe oral contraceptives through telemedicine.

Selma AIDS Information and Referral (AIR), Inc. is Alabama’s only African American-led AIDS service organization. Primarily funded by the Ryan White program, they serve nearly 200 HIV positive clients a year across eight Black Belt counties, providing HIV/AIDS information, counseling, referrals, support groups, and peer counseling. They also offer HIV tests, substance use and mental health counseling in-person or by video conference, and social services such as transportation, housing support, medication assistance, and a food bank, with a particular focus on formerly incarcerated people and those with substance abuse disorders. Selma AIR’s clients are referred to the MAO clinic in Selma housed at UAB for medical care and treatment. Selma AIR has a high patient retention rate, partly because they have a dedicated caseworker who is familiar with the community and takes extra measures to ensure confidentiality. Selma AIR has had a significant impact in the community, with local media reporting new HIV diagnoses decreasing by nearly 60% in Dallas and Wilcox counties and by over 40% in other Black Belt counties serviced by Selma AIR since its inception in 1995. |

Social Determinants of Health

Social determinants such as housing, employment, education, and poverty play a sizable role in the health of Dallas County residents, contributing to high rates of chronic conditions. In addition, historical and current racism has reportedly fostered mistrust of the medical establishment among the African American community.

High poverty rates, limited affordable housing, lack of vocational training and employment opportunities, and other socio-economic stresses lead many women to prioritize other needs before health care and family planning. Almost a third of the population (32%) in Dallas County lives below the federal poverty level.3 Focus group participants discussed a scarcity of well-paying jobs and challenges with childcare among their daily concerns. One provider pointed out that without transportation or childcare, women living in rural areas will not come into Selma for health care unless they are in pain and that other financial priorities such as food and housing are more pressing. These factors also contribute to high rates of chronic conditions such as diabetes (including among pregnant women), hypertension, obesity, and kidney disease.

“Social determinants of health play a big role. If they don’t have food in the fridge, they will not be worrying about birth control; that’s the last thing on their list.”

–Dallas County Health Department staff“The whole village has to be involved. It can’t be just the church, the school, or the home; the whole puzzle has to be put together. All these entities have to be part of the discussion, and we have failed so far.”

–Felecia Lucky, President, BBCF“[My health] is not a ten [on a scale of ten] because I have other things I have to deal with concerning my kids, their health, their wellbeing, my financial situation; all of that is constant for my health. If [they’re] okay, then I can deal with it.”

–Focus group participant

Historical mistrust of the medical establishment among the African American community may contribute to lack of engagement in early and preventive care. Some interviewees commented on the lasting effect of slavery, racism, and the notoriously unethical Tuskegee syphilis study, conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service in the mid-1900s in nearby Macon County. The legacy of that experiment, slavery, and the Jim Crow era still lives on in the area today. Interviewees discussed a need for more African American providers who could provide culturally congruent care, along with cultural sensitivity training for existing providers. A new Ob-Gyn at the hospital OB clinic is an African American female, which she views as important for her patients.4

“The history of racism weighs on the community heavily.”

–Felecia Lucky, President, BBCF“Black women are not believed about their issues and their pain.”

–June Ayers, Director, Reproductive Health Services (RHS)

| Initiative: Supporting regional community development |

| The Black Belt Community Foundation (BBCF) was created in 2004 and covers 12 counties across the Black Belt region. BBCF has granted more than $3 million to nonprofit organizations, focusing their efforts on four key areas: arts and culture, education, health and wellness, and community economic development. They have funded key health projects including Selma AIR and a health and wellness program in nearby Sumter County to help provide medication to people lacking access. Other projects have included education about AIDS and domestic violence, which they note is a growing need in the area. BBCF also implemented a matched savings program to help low-income individuals buy a car or afford housing or education. |

Contraceptive Provision, Access, and Use

Focus group participants and interviewees said that a lack of sex education, the influence of the churches, and cultural norms have contributed to the high rates of teen pregnancy in the area. The Dallas County Health Department is a key provider of contraception for low-income women.

The Dallas County Health Department, the local Title X provider, is the primary resource for contraception in the community and has an extensive case management program; however, resources and capacity are limited. The health department located in Selma serves approximately 3,000 women a year from Dallas County and some of the surrounding counties. It assists uninsured women to enroll in Plan First and is the primary provider of family planning for low-income women in the region. They offer a wide range of methods including emergency contraception, the Depo-Provera shot, oral contraceptives, and implants. At the time of the site visit, women requesting IUDs were referred to a community provider, but the health department was training a clinician to insert IUDs onsite. The health department also provides family planning education and counseling, and extensive case management for patients with myriad challenges related to housing, food, domestic violence, and other needs. Social workers work with teens, reminding them to come in to refill their contraception on time. They also conduct outreach, but interviewees reported that health department does not have the resources to fully meet the needs of the community.

“It’s easy [be]cause you can go to the health department and get everything free.”

–Focus group participant

There are a range of Plan First providers in the county including private physicians’ offices, the RHMP, and the hospital outpatient obstetric clinic, but most focus group participants go to the health department because it is convenient, the providers “understand” them, and services are confidential and free.

Interviewees and focus group participants reported that most women use Depo Provera to prevent pregnancy. Focus group participants said they could get the Depo shot right at the health department, but they noted a “two-step” process at other clinics in which they had to go to the clinic to get a prescription, go to the pharmacy to pick up the shot, and then return to the clinic to get the shot. For women seeking an IUD after giving birth, the Selma hospital does not offer immediate postpartum IUDs. Focus group participants also described challenges obtaining tubal ligations after delivery related to Medicaid policies and scheduling. Some focus group participants said that it is difficult to get an appointment with the hospital outpatient OB clinic. At the time of this study, RHMP was in the process of establishing an MOU with Ob-Gyns serving Medicaid patients to facilitate easier referrals.

Role of Religion and Sex Education

Comprehensive, medically accurate sex education is not usually offered in Dallas County schools. Interviewees and focus group participants said that the lack of health literacy and sex education in the schools contributes to high rates of STIs, HIV, and teen pregnancy. Alabama requires two weeks of HIV education be provided in public schools but does not require general sex education. Interviewees felt that the HIV education requirement is not enforced uniformly within the state, and that schools vary in whether and how they teach sex education, generally focusing on abstinence rather than more comprehensive approaches. Interviewees reported that these factors resulted in a lack of knowledge about STIs, misinformation about contraceptive methods, and numerous HIV cases among students in the area. Selma AIR, which provides HIV education from 5th through 12th grade in every school in its service region, reported that some school nurses and teachers invite them in to teach abstinence as a method of HIV prevention, but that they would prefer to teach more effective evidence-based approaches. A local community development organization highlighted the impact of the lack of resources at the state and local level; they added that sex education is not a priority because schools “are trying to figure out how to keep the lights on.”

“For communities that are already struggling and resources are tight, you bring in another curriculum and add it onto their plate, people become resentful and don’t do a good job. There have to be resources available to support the additional ask from the state level.”

–Felecia Lucky, President, BBCF

Interviewees reported that although there are a small number of churches (e.g., Methodist, Unitarian Universalist) that promote family planning and STI information at community events, the majority of churches do not. Interviewees noted that some churches are strongly opposed to discussing family planning and STI prevention because they believe that sex or pregnancy before marriage is shameful. At the same time, several interviewees suggested that teen pregnancy has been normalized because it is so common.

“There is a community attitude that if you are a woman without kids, it’s weird.”

–June Ayers, Director, RHS

Access to Abortion Counseling and Services

There are no clinics providing abortion in Dallas County. Substantial local opposition to the service was noted among both focus groups participants and interviewees.

There is no abortion provider in Dallas County, and obstacles such as transportation, anti-abortion sentiment, and cost make it difficult for women to obtain an abortion. The closest abortion clinic to Selma is located 50 miles away in Montgomery, where staff reported seeing many patients from the Selma area. There used to be an abortion provider in Selma, but intense protesting and a reported problem with state licensure caused it to close. The sole hospital in Dallas County does not perform abortions even in cases of life endangerment or lethal fetal anomalies. Instead, they refer patients to tertiary clinics in Birmingham or Montgomery. Women whose pregnancies are a result of rape or incest are reportedly referred to rape counseling. According to one interviewee, many health care providers are anti-abortion, and some women seeking an abortion are reportedly told “to get out of their office and never come back.”

“I have a patient with a basketball-sized fibroid and a 6-week pregnancy in lower Mississippi. We cannot do an abortion in an office-based setting and get insurance to cover it. She would die if she continued the pregnancy; she needs an abortion AND hysterectomy. [It’s been] really difficult to get this woman the appropriate care even though you can justify it in a hundred different ways. …[there’s] no local Ob-Gyn or hospital that will provide abortion here.”

–June Ayers, Director, RHS“You ain’t gonna get [an abortion] here, not in Selma.”

–Focus group participant

Cost is cited as a barrier to abortions for many low-income women, with the procedure fees ranging from about $600 to $1,500, depending on the gestational age. In Alabama, Medicaid will not pay for abortion outside of the exceptions of rape, incest, or life endangerment of the woman, but the Montgomery-based clinic reported that they have never been able to get an abortion paid for even under these circumstances. The Yellowhammer Fund assists women seeking abortions with the cost of the procedure; they reported providing about $80,000 in financial assistance in 2018. Since the state passed its near-total abortion ban in 2019, donations to Yellowhammer have risen, and the Fund has increased assistance to cover the procedure from about $650 per week to about $9,000 per week, helping 20 to 40+ women per week pay for abortion services. The Fund also has a budget of $4,000 per month for other logistical support such as transportation. Because many low-income women do not have bank accounts, especially those from rural areas, the Fund also provides gift cards (rather than transferring funds into an account electronically) to women to pay for gas or to rent a car to travel to their appointment.

| Initiative: Community-based abortion support services |

| Montgomery Area Reproductive Justice Coalition (MARJCO)’s offices are housed at People Organizing for Women’s Empowerment & Rights (The P.O.W.E.R House), a historical building next door to Reproductive Health Services (RHS), the only abortion provider in and south of Montgomery. MARJCO, a volunteer organization, offers clinic escort services for patients coming for care at RHS. They also allow family (including children with an adult companion) and friends to wait in the house or on their porch while patients are inside the clinic. Because many women must travel long distances to get to Montgomery for abortion services and because of the mandated 48-hour waiting period, MARJCO can arrange for these women to stay at the P.O.W.E.R. House before their procedure. They also host events to advocate for reproductive rights, provide space for community groups, and offer classes on sex education and contraception. |

Highly restrictive state laws and widespread anti-abortion sentiment in the community make it difficult to provide or obtain an abortion. Interviewees cited the 48-hour waiting period and requirement that abortion practitioners have admitting privileges at a local hospital as particularly limiting. The Montgomery abortion clinic explained that the 48-hour waiting period is misleading; because they are a small clinic, they perform abortions only one day a week, so depending on when the woman comes in, she may have to wait up to nine days for her procedure.

Providers also spoke of the anti-abortion sentiment in the community. There are protesters outside the Montgomery abortion clinic every day, which escalates on procedure days. Interviewees reported that many clinics would not last long in the area because “people are very against abortion in this state.” They reported that abortion providers cannot live in the same community in which they work due to harassment. Montgomery Area Reproductive Justice Coalition provides escort services into the clinic, overnight accommodations, and other supports for women traveling to Montgomery for abortion services.

“When [women] get out of the car they are getting screamed at. The [protesters] don’t care how they shame them, how startling it is. Some patients come in and they are angry, and others in tears. They have to go through this twice…we prepare the patients about what to expect. Protestors will video patients and providers, and post them on Facebook. This feeds the culture [of stigma].”

–June Ayers, Director, RHS

Alabama signed the most restrictive anti-abortion measure into law on May 15, 2019. Scheduled to begin in November 2019, it would make abortion a felony except when necessary to prevent serious health risk to the woman, punishable by up to 99 years in prison for the providing physician. This law, passed after this case study was conducted, is temporarily blocked by court order. At the time of this publication, state law allows abortion up to 20 weeks.

“We don’t want to defend abortion access. We want to improve abortion access in Alabama.”

–Amanda Reyes, Executive Director, Yellowhammer Fund“I can’t think of [just] one policy that affects abortion access. It’s more of an avalanche…There is such an animosity to anything that has to do with reproductive rights.”

–June Ayers, Director, RHS

Some providers refer women to the crisis pregnancy center (CPC) in Selma for assistance, unaware of its anti-abortion mission. CPCs typically offer limited medical services such as pregnancy tests and ultrasounds, and discourage women from seeking abortions. The health department in Selma lists Safe Harbor, a local CPC, as a referral for “abortion services” above abortion providers in Montgomery and Tuscaloosa. About half of the focus group participants reported knowing that Safe Harbor provides free pregnancy tests but not contraception. Participants who had gone there reported that they were shown a video about abortion. Two other focus group participants had gone to CPCs in Montgomery and Birmingham for pregnancy tests, where clinic staff pushed adoption as an option and asked the women to read the Bible.

Focus group participants were opposed to abortion, and most thought the procedure is illegal in Alabama. Some interviewees believed that a lack of education about abortion contributes to the anti-abortion environment. One interviewee stated, “If everything they have heard is negative about abortion, if they have heard these messages and no one has sat down to explain to them the positives and negatives, the planning beforehand, there is a huge gap.” All focus group participants expressed opposition to abortion, but some said they were okay with abortion if the pregnancy is life threatening. Two participants shared that they had had an abortion; one said it was a Medicaid-funded abortion because of life-threatening pregnancy and the other was due to a fetal anomaly.

“I’m against abortions, so therefore if that condom broke and I ended up pregnant, I’m just pregnant.”

–Focus group participant“I’m against them, but me personally I had to have one because I had a choice of I live or the baby live, so I ended up getting an abortion…”

–Focus group participant

The focus group identified considerable misinformation about abortion services among women in the community. Most focus group participants incorrectly believed that abortion is illegal in the state, and only half knew where you could get one. Most also incorrectly equated emergency contraception (EC) with abortion, but they knew that you could get EC at the health department or buy it over the counter. Another participant incorrectly thought abortion threatens future pregnancies.

“Abortions happen in Alabama every day. The problem is we don’t talk about it.”

–Mia Raven, Founder & Executive Director, The P.O.W.E.R. House“It’s being where we are, in the Bible belt. It’s not educating people. Someone this past week who has had four previous abortions, she still asked me if this abortion will cause her to be infertile. Patients don’t know what they have access to. A big root of this is educating in the state, which we don’t do.”

–June Ayers, Director, RHS

Conclusion

Dallas County has a network of community-based organizations and health care providers that are committed to improving the health and well-being of women living in the Black Belt region of Alabama, despite considerable structural challenges in the community. Several interviewees said that Alabama’s decision not to expand Medicaid and its strict eligibility limits means many low-income women remain uninsured or only have coverage for family planning services. Women in the county, including those in Selma, suffer from high rates of chronic health conditions and face substantial barriers to care including poverty, unemployment, lack of transportation, unaffordable housing, and limited education. In addition, due in part to provider shortages and hospital closures, women living throughout the Black Belt have to travel long distances to access obstetrical care, exacerbating high rates of infant and maternal mortality. The heavy influence of churches and the state’s politically conservative climate have resulted in limited sexual health education, and stigmatization and restriction of abortion care.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of the interviewees that participated in the structured interviews for their insights, time, and helpful comments. All interviewees who agreed to be identified are listed below. The authors also thank the focus group participants, who were guaranteed anonymity and thus are not identified by name.

June Ayers, Director, Reproductive Health Services

Keshee Dozier-Smith, CEO, Rural Health Medical Program, Inc.

Meneka Johnson, PhD, COO, Rural Health Medical Program, Inc.

Felecia Lucky, President, Black Belt Community Foundation

David McCormack, CEO, Vaughan Regional Medical Center

Clara Moorer, Director, Women’s Health Services, Vaughan Regional Medical Center

Rhonda Parr, Nurse Coordinator, Dallas County Health Department

Mia Raven, Founder & Executive Director, Montgomery Area Reproductive Justice Coalition (MARJCO)

Amanda Reyes, Executive Director, Yellowhammer Fund

Terri Sewell, U.S. Rep. (AL-07)

Sarina Stewart, LMSW, Social Work Manager, Dallas County Health Department

Suzanne Terrell, LMSW, Assistant Administrator, Dallas County Health Department

Medical Advocacy & Outreach (MAO) Staff:

Marguerite Barber-Owens, MD, AAHIVS

Laurie Dill, MD, AAHIVS, Medical Director

Stephanie Hagar, LBSW Lead Administrative Social Worker

Rozetta Roberts, NP, Clinic Director

Dianne Teague, Governmental/Donor Affairs

Jennifer Thompson, LICSW, Division Manager of Social Work

K.C. Vick, Director of Capacity Building