Ten Things to Know About Medicaid’s Role for Children with Behavioral Health Needs

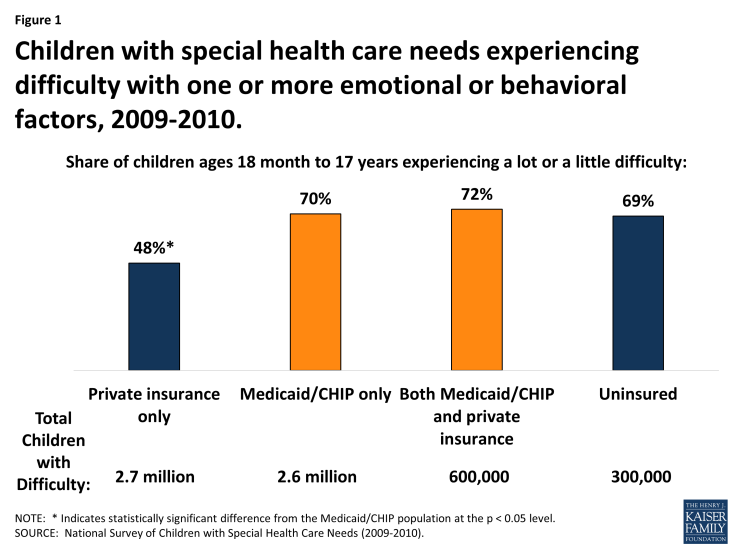

Children with special health care needs have or are at increased risk for chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional conditions and also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally. There are 11.2 million children with special health care needs as of 2009-2010, and 59% (6.4 million) of them have one or more emotional or behavioral difficulties, such as depression, anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or autism spectrum disorders. Among this population are 3.2 million Medicaid/CHIP children reporting special health care needs including one or more emotional or behavioral difficulties. They include 2.6 million covered by Medicaid/CHIP alone, and 600,000 covered by both Medicaid/CHIP and private insurance. These children often require services that may not be offered at all, or for which coverage may be limited, under private insurance, such as assertive community treatment, family psychosocial education, and basic life and social skills training. Receiving needed behavioral health treatment enables children to reach developmental milestones, progress in school, and participate in their communities.

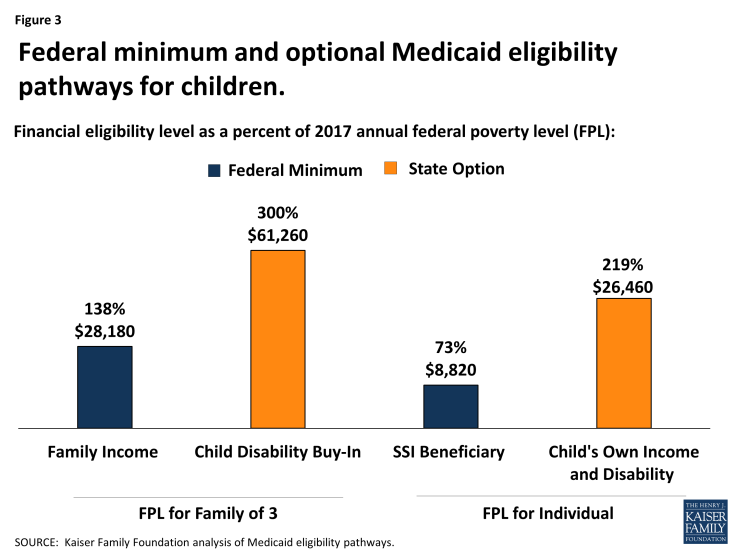

Medicaid plays an important role for many children with behavioral health needs. It provides comprehensive coverage for children and makes treatment affordable by limiting out-of-pocket costs. Medicaid is the only source of health coverage for many children in low and middle income families. It also covers services that are excluded from private coverage or for which private coverage is limited for children with private insurance. Nearly all Medicaid services for children are mandatory under the program’s Early, Periodic, Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment benefit, which requires states to cover services “necessary. . . to correct or ameliorate” a child’s physical or mental health condition; home and community-based services provided under Section 1915 (c) waivers are optional. States participating in Medicaid must cover children in families with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL, $28,180 for a family of three in 2017) and children who receive Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits (equivalent to 73% FPL in 2017). States can opt to expand Medicaid eligibility for children with significant disabilities at higher income levels, and nearly all do.

Medicaid currently provides federal matching funds with no pre-set limit to help states cover children with behavioral health needs. Restructuring Medicaid financing as proposed in the American Health Care Act could limit states’ ability to care for these children. Under a per capita cap, states would be pressed to finance new treatments or medications that increase per enrollee spending or to enroll a large share of children with special health care needs for whom coverage is optional. Faced with a reduction in federal funding, states may look to reduce provider payment rates, eliminate optional services, or restrict optional eligibility pathways. The following series of graphics highlights Medicaid’s role for children with behavioral health needs.

- Larger shares of Medicaid children with special health care needs report emotional or behavioral difficulties, compared to those with private insurance only, as of 2009-2010.

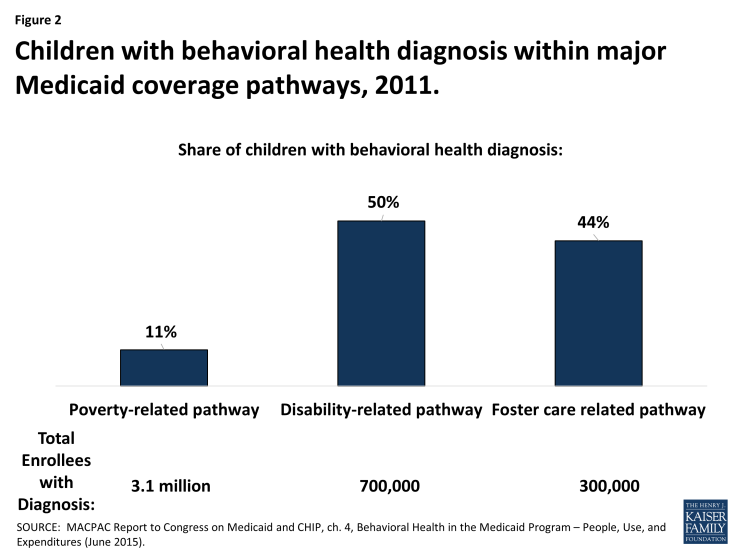

- Half of children eligible for Medicaid based on a disability have a behavioral health diagnosis, compared to 44% of those eligible based on foster care, and 11% of those eligible based on poverty, as of 2011.

- States have flexibility to expand Medicaid eligibility, and receive federal matching funds, for children with disabilities, including those with behavioral health needs.

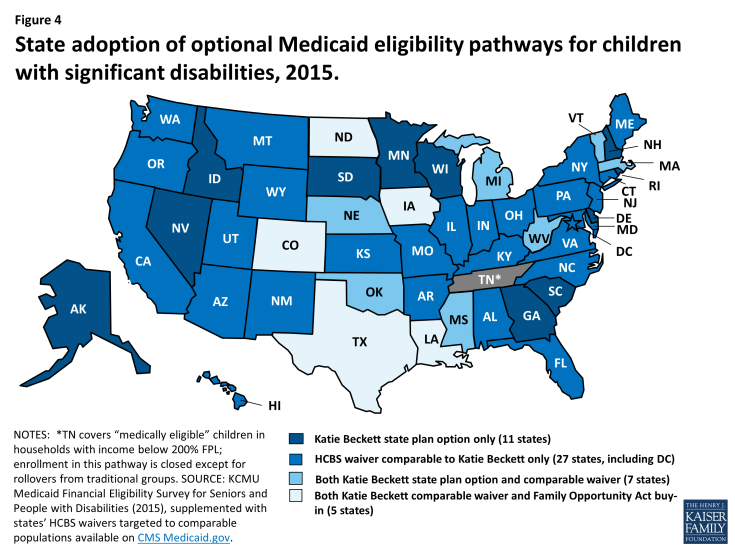

- Nearly all states expand Medicaid eligibility to cover children with significant disabilities, as of 2015.

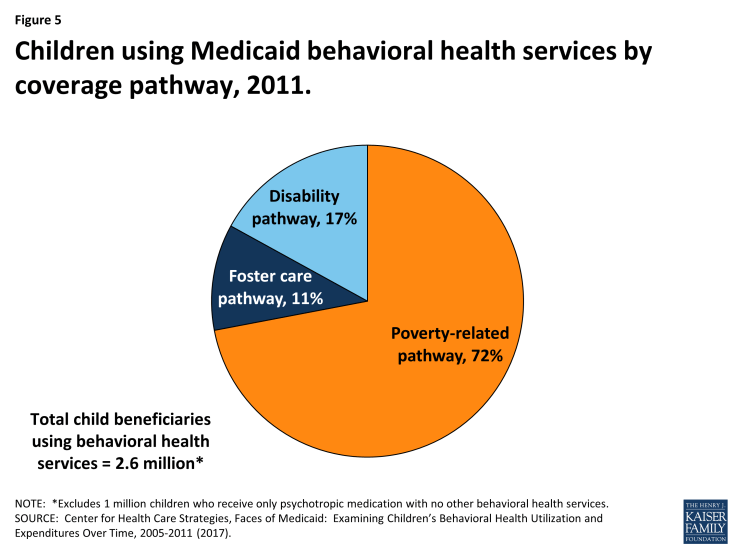

- Nearly ¾ of children receiving Medicaid behavioral health services are eligible based on poverty alone.

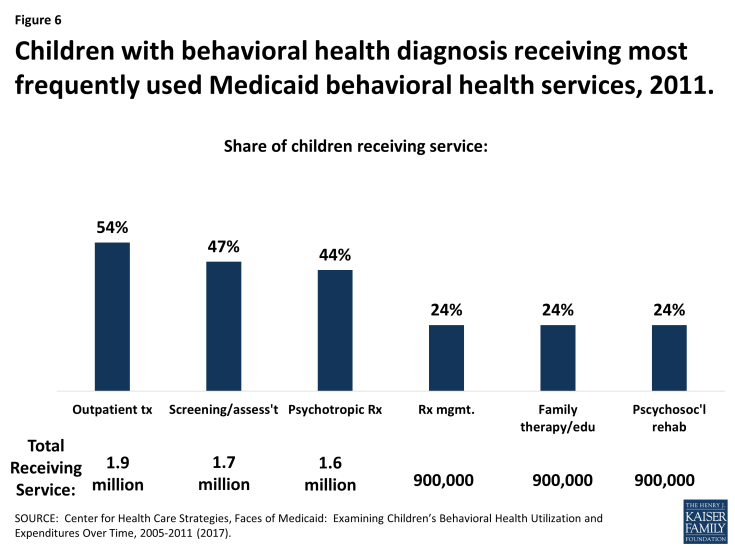

- Over half of Medicaid children with behavioral health diagnoses are receiving outpatient treatment.

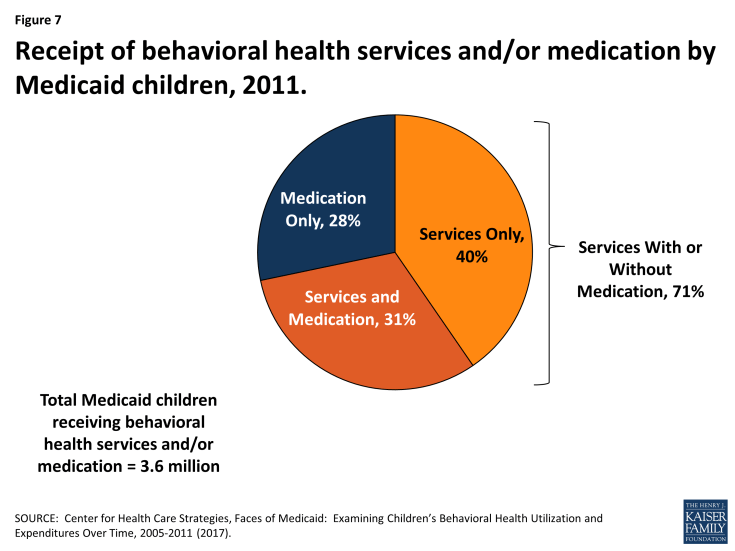

- Among Medicaid children receiving behavioral health services and/or medication, over 70% received services (with or without medication) as of 2011. Less than 30% received medication only.

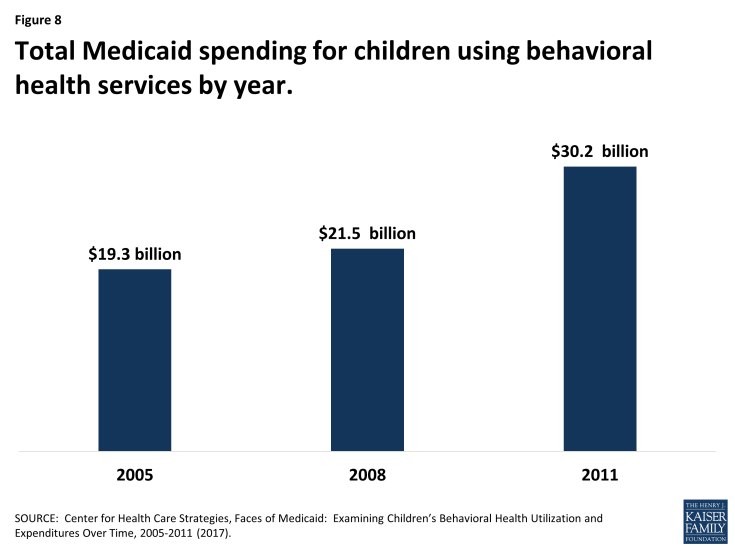

- Total Medicaid spending for children using behavioral health services has grown over time.

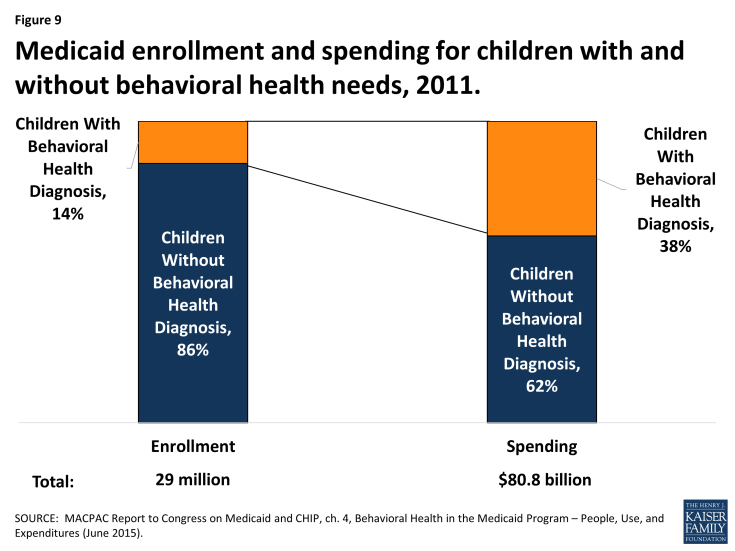

- Due to their greater needs, Medicaid children with behavioral health needs account for 14% of enrollment but 38% of spending, as of 2011.

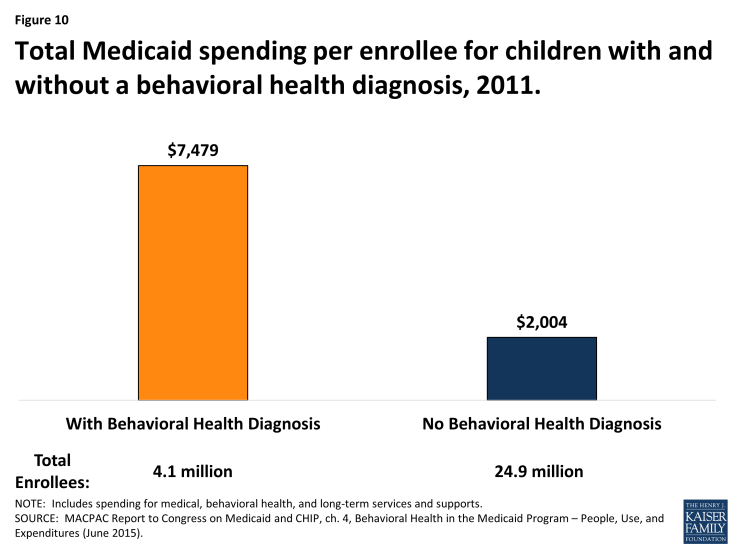

- Given their greater needs, total Medicaid spending per enrollee (including medical, behavioral health, and long-term care services) is nearly four times higher for children with a behavioral health diagnosis compared to those without, as of 2011.