Serving Low-Income Seniors Where They Live: Medicaid's Role in Providing Community-Based Long-Term Services and Supports

Seniors managing chronic health conditions or experiencing an age-related decline in physical or cognitive functioning may need long-term services and supports (LTSS) to complete daily self-care activities (such as eating, bathing or dressing) or household activities (such as preparing meals or doing laundry). LTSS include a range of services, including adult day health care programs, home health aide services, personal care services, and case management services, among others.1 LTSS needs may be met through both paid services and unpaid services provided by friends or family members. While some people who need LTSS choose or require care based in nursing facilities, most people with LTSS needs live in the community. (See related videos on seniors with LTSS needs in Virginia and Kansas.)

Medicare is the primary source of health insurance for nearly all seniors, but the program does not cover LTSS, and few Medicare beneficiaries have private insurance that covers these services. For some low-income Medicare beneficiaries (called “dual eligible beneficiaries”), Medicaid fills this gap by providing wraparound coverage for a range of services, including LTSS. Helping these individuals remain in the community rather than reside in a nursing facility is a goal of both beneficiaries and states, in part due to the Americans with Disabilities Act’s community integration mandate.2 Understanding the community-based LTSS population served by Medicaid is important for designing effective care delivery systems, particularly as states are increasingly developing new systems of integrated and managed care for this population, and because Medicaid is the nation’s primary payer for LTSS.3

In addition, other low-income seniors may have LTSS needs but may not meet Medicaid eligibility criteria or be enrolled in the program. Some Medicaid waiver programs that provide home and community-based LTSS have waiting lists for coverage.4 Since many of these people may become eligible for Medicaid should they ever need institutional-based LTSS, it is important to understand the needs and characteristics of this population as well as that already served by Medicaid.

To better understand the low-income population with LTSS needs, including those covered by Medicaid and those who are not, this issue brief examines the need for LTSS among seniors who live in the community5 and need LTSS. We use the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) to examine rates of need for LTSS and detail the characteristics of seniors who need these services. Throughout the brief, we compare dual eligible beneficiaries to low-income seniors without Medicaid. We also examine a third group, higher income seniors without Medicaid, to understand the role of income. Because LTSS needs increase with age, we also examine differences by age. A full description of the NHATS data and the analytical approach are included in the methods section at the end of this issue brief.

The need for LTSS among seniors living in the community

LTSS needs are relatively common among seniors living in the community. Overall, 46 percent of seniors in the community report having any type of LTSS need (data not shown). LTSS needs fall into two major categories: self-care needs and household activity needs.

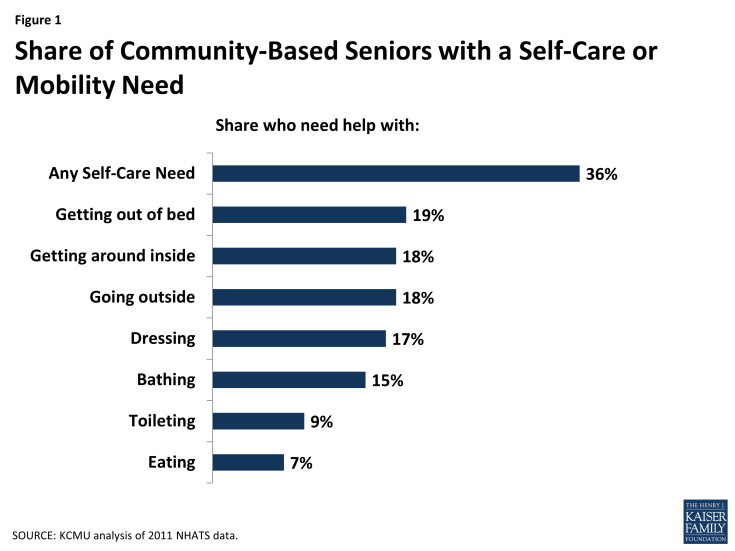

Sometimes called “activities of daily living,” self-care needs (e.g., bathing, dressing, or eating) are those considered essential to daily functioning. The number and extent of such needs are used as the basis to determine Medicaid eligibility for LTSS. More than a third (36%) of seniors in the community have a self-care or mobility need (Figure 1). With the exception of toileting and eating (which are less common), different types of self-care/mobility needs (bathing, dressing, going outside, getting around inside, and getting out of bed) are about equally prevalent. While Medicaid eligibility standards may require that an individual have several self-care needs, even having one self-care need could be incapacitating if that need is unmet.

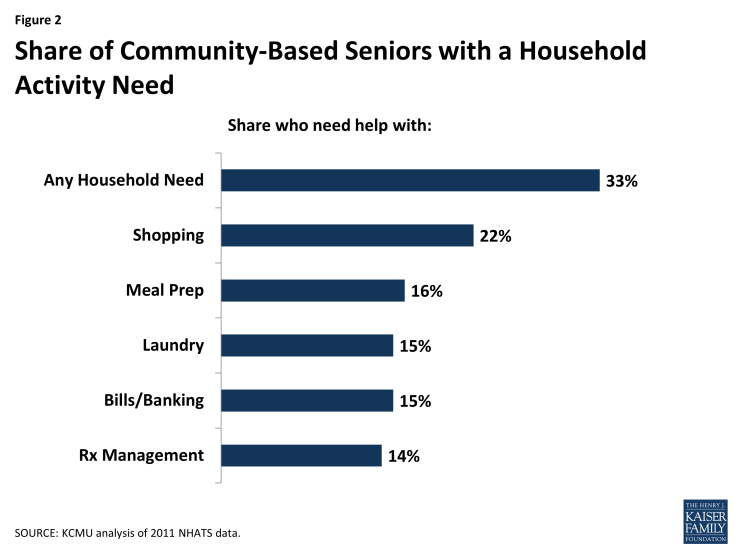

Household activity needs (e.g., preparing meals or managing medication) are sometimes called “instrumental activities of daily living.” Household activity needs are also common, with a third (33%) of seniors in the community having such a need (Figure 2). Within household activity needs, different types of needs (help with meal preparation, laundry, paying bills, and medication management) were about equally prevalent, with the exception of shopping for groceries or personal items, which was more common. While not as essential to functioning as self-care needs, household activity needs are an important measure of a person’s ability to live independently in the community.

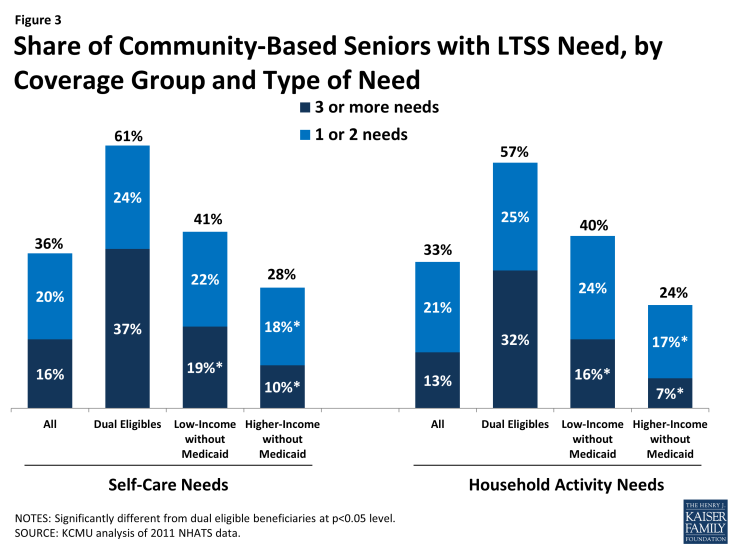

The need for LTSS is more common among some groups of seniors than others. Dual eligible seniors are more likely to have an LTSS need than low-income seniors who do not have Medicaid. Almost seven in ten dual eligible beneficiaries reported an LTSS need, a significantly higher rate than among low-income seniors without Medicaid (52%) or higher-income seniors without Medicaid (36%) (data not shown). This pattern holds across different types (household and self-care) of need (Figure 3). Dual eligible beneficiaries also are more likely than other seniors to report having three or more LTSS needs. This finding in part reflects Medicaid eligibility policy: seniors may become eligible for Medicaid LTSS coverage based on their low income and functional needs or by “spending down” their income and resources to cover medical and LTSS expenses. However, many low-income seniors who do not have Medicaid also need LTSS. Unless these individuals have private insurance coverage for LTSS, they must pay out-of-pocket for services, rely on family or friends, or go without needed services. For low-income seniors without Medicaid, accessing needed services may be particularly difficult, given limited resources.

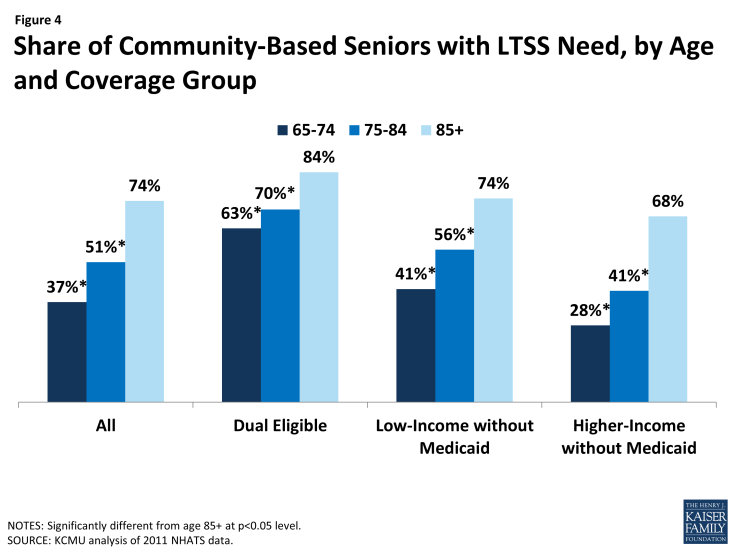

Not surprisingly, older seniors are most likely to need LTSS. Compared to 37% of seniors aged 65 to 74 and about half of those aged 75-84, nearly three quarters (74%) of those aged 85 and older have an LTSS need (Figure 4 and Table 1). This pattern is expected given that functioning declines with age, but it also demonstrates high levels of need among the “very old” (age 85+) who may face additional challenges in accessing needed services (such as transportation or mobility limitations). It also indicates that, as the population ages, overall rates of need for LTSS may increase. Differences in rates of need by age exist among both dual eligible beneficiaries and seniors without Medicaid, though dual eligible beneficiaries at all ages are more likely to need LTSS than both other low-income and higher-income seniors without Medicaid. Again, different rates of need by coverage group reflect Medicaid’s role in providing assistance to those with LTSS needs.

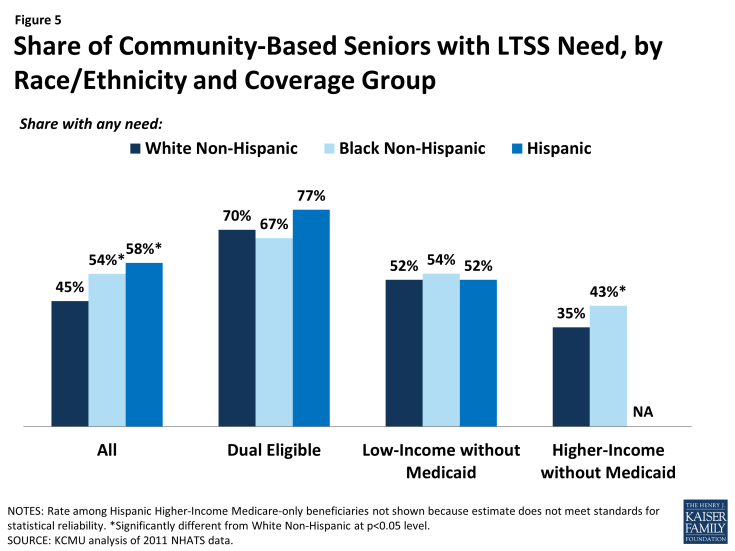

Women also are more likely to need LTSS, with more than half of elderly women (52%) having an LTSS need compared to four in ten men. Even controlling for coverage group/income and age, women are more likely than men to need LTSS (see Table 1). In addition, people of color are more likely to have an LTSS need than White, Non-Hispanics. More than half of Black (54%) or Hispanic (58%) seniors have an LTSS need, compared to 45 percent of White Non-Hispanics. Some of the differences in rates of need by race/ethnicity likely reflect income; when examining rates of need within income/coverage group, there was no difference in rates of need by race/ethnicity among either dual eligible beneficiaries or low-income seniors without Medicaid (Figure 5 and Table 1).

Lastly, most seniors (about 90%, data not shown) are linked to a regular source of health care and the percentage with LTSS need is higher than among the small percentage of seniors who are not linked to care. However, nearly four in ten (38%) seniors who say they do not have a regular health care provider need LTSS, and three in ten who have not seen a regular provider in the past year need LTSS (Table 1). While these rates of need are lower than those among seniors who do have regular providers or did see their provider in the past year, they indicate relatively high levels of need among seniors who do not appear to be linked to a regular source of care. Health care providers may be an important resource for screening for LTSS needs and connecting low-income people to Medicaid coverage and services, and people who are not linked to care may be harder to reach. Identifying people with LTSS needs as early as possible and connecting them to services can be cost-effective over time by preventing or postponing the need for more intensive services or institutional care as functioning declines due to unmet needs.

Understanding the population of seniors with LTSS needs

In recent years, many states have undertaken efforts to coordinate Medicaid LTSS with other services, including both those provided by Medicaid and by Medicare, or to actively manage LTSS through managed care programs. Understanding the health and social characteristics of seniors with LTSS needs can help policymakers design programs to address the needs of this population. Among both dual eligible beneficiaries and low-income seniors without Medicaid, most seniors with an LTSS need have physical or mental health problems and live in a private residence. However, there are notable differences between the LTSS population served by Medicaid and the LTSS population that does not have Medicaid: Medicaid beneficiaries are frailer in that they have poorer health, higher rates of mobility impairment, and higher rates of cognitive impairment or mental illness. They also are more likely to live alone or in poor housing conditions. Still, the population of low-income seniors without Medicaid who need LTSS also is vulnerable, with notable shares having significant physical or mental impairment and living in arrangements that may make it difficult to obtain needed assistance.

Health Status and Mobility Limitations

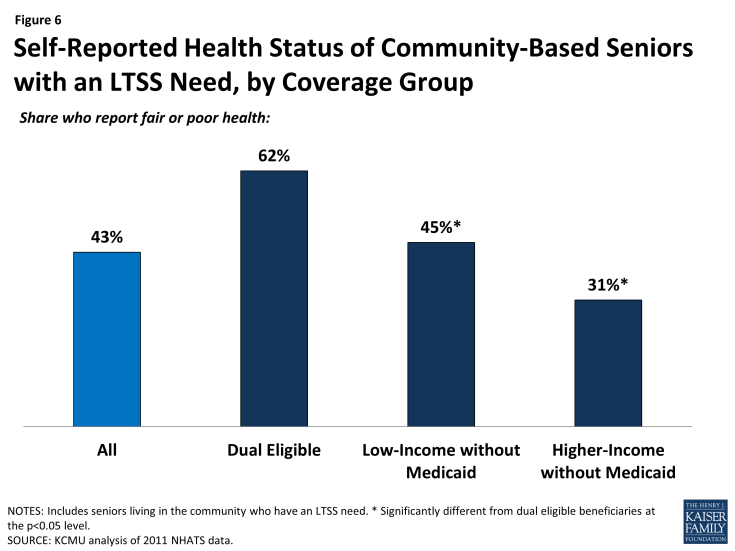

Poor health and the need for LTSS are closely related. Overall, over half (57%) of seniors with an LTSS need live with at least three chronic conditions (such as high blood pressure, arthritis, osteoporosis, diabetes, or heart disease6), and this rate is similarly high among dual eligible beneficiaries and low-income seniors without Medicaid with an LTSS need (Table 2). While not surprising, these patterns show a strong relationship between physical illness and LTSS needs. Similarly, many (43%) seniors with an LTSS need say their overall health is fair or poor, though dual eligible beneficiaries are more likely than low-income seniors without Medicaid to say that their overall health is fair or poor (Figure 6). This difference may reflect dual eligible beneficiaries having more complex health needs or comorbidities than seniors without Medicaid.

Figure 6: Self-Reported Health Status of Community-Based Seniors with an LTSS Need, by Coverage Group

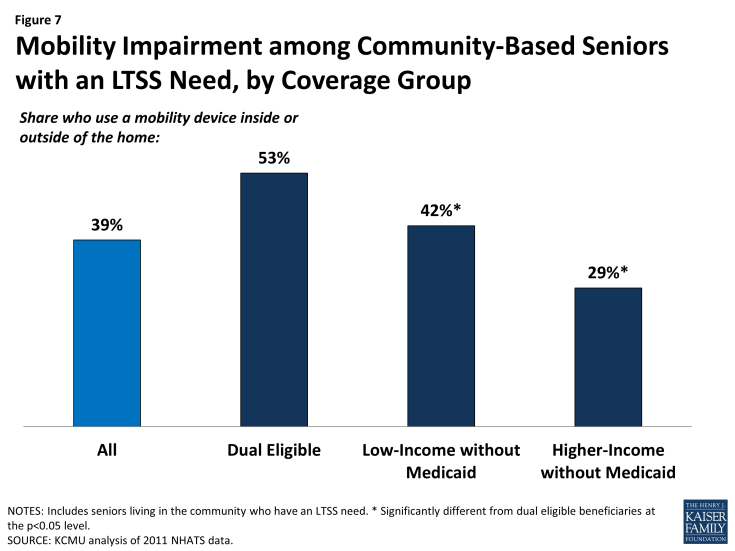

Mobility problems are also common among seniors with LTSS needs. Overall, nearly four in ten (39%) seniors with an LTSS need use a mobility device (cane, wheelchair, walker or scooter) either inside or outside their home. Among dual eligible beneficiaries with an LTSS need, however, rates are higher, with more than half (53%) requiring a mobility device in or outside the home (Figure 7). Though older (age 85+) beneficiaries in all coverage/income groups are more likely to use a mobility device than younger seniors, the pattern of dual eligible beneficiaries being more likely to use mobility devices holds across age groups (Table 2). This finding may point to a need for special transportation programs for dual eligible beneficiaries, particularly if they require health or social services outside the home.

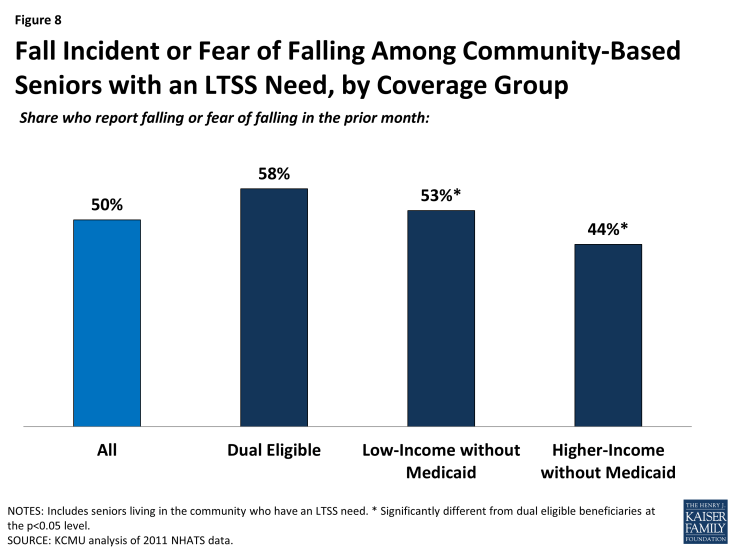

Figure 8: Fall Incident or Fear of Falling Among Community-Based Seniors with an LTSS Need, by Coverage Group

Falls are a serious problem among older adults, occurring frequently and leading to serious injury or even death; fear of falls is also common and can lead to self-imposed restrictions on activity that in turn contribute to mobility impairment.7 Indeed, corresponding to mobility impairments, half of seniors with an LTSS need report that they have either had a fall or feared falling in the prior month, and dual eligible beneficiaries with an LTSS need are more likely than other seniors to report falling or having a fear of falling (Figure 8). However, because fall incidents or risk increase with age, among seniors with an LTSS need in the age groups 75-84 or 85+, there is no difference across coverage/income groups in the likelihood of falling or fear of falling (Table 2). Because falls lead to increased health care utilization and costs,8,9 high rates of falling and fall risk may be of concern for programs serving the community-based LTSS population.

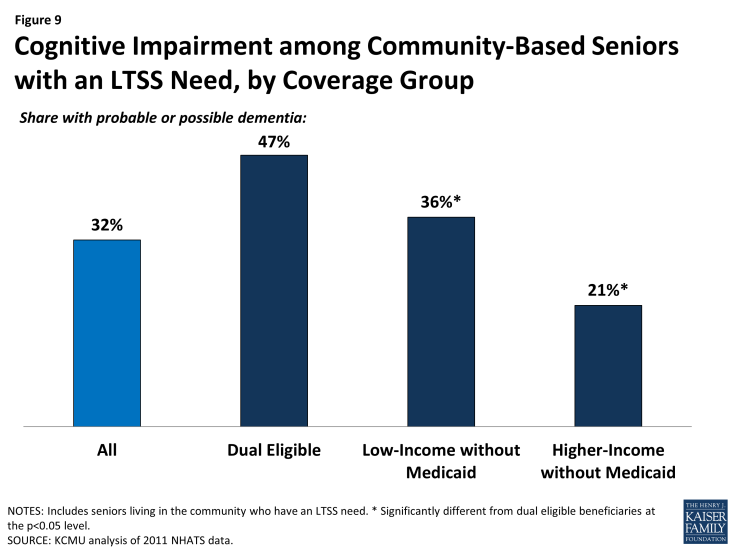

Similar to those with physical limitations, people with cognitive impairments may require extra assistance and substantial supervision in managing day-to-day self-care or household activities. They may also be particularly challenging to serve, as these impairments sometimes manifest in difficult behavior. Overall, nearly one in three (32%) seniors with an LTSS need has a cognitive impairment, defined here as possible or probable dementia.10 However, among dual eligible beneficiaries, the rate is 47 percent, significantly higher than among seniors without Medicaid (Figure 9). The likelihood of having a cognitive impairment increases with age, and by age 85, there are no statistical differences in the prevalence of cognitive impairment between dual eligible beneficiaries and low-income seniors without Medicaid (Table 2). Recently proposed federal regulations for staffing in nursing facilities call for additional training in caring for people with dementia,11 but no similar federal requirements exist for care delivered in the community.12 Thus, states and other programs serving the LTSS population in the community may need to develop their own guidelines to ensure best practices in caring for the seniors with dementia or other cognitive impairment.

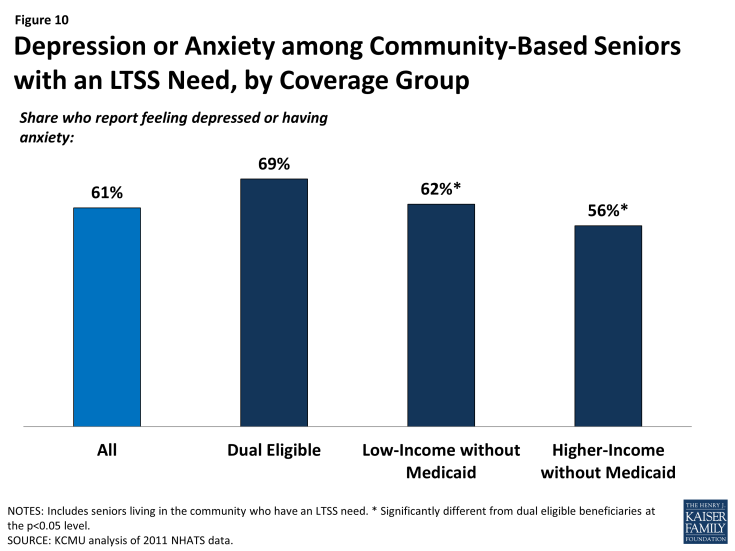

Integrated care that coordinates physical and behavioral health is a goal of many recent initiatives to serve the LTSS population in the community. More than six in ten (61%) seniors with an LTSS need report feeling depressed or having anxiety. Among seniors with an LTSS need, dual eligible beneficiaries are more likely than seniors without Medicaid to report symptoms of depression or anxiety (Figure 10). These patterns vary when looking at specific age groups, as rates of depression and anxiety generally even out between coverage/income groups at older ages (Table 2). As with the high prevalence of physical comorbidities or multiple chronic conditions, high rates of behavioral health need among people with LTSS needs may represent an opportunity for additional coordination of services.

In addition to maintaining self-sufficiency and promoting independence, delivering care in the least-restrictive setting, and lowering long-term care costs, a central goal of helping people with LTSS needs remain in the community is to preserve social networks and community integration. Notably, among seniors with an LTSS need, only 6 percent say they have no one to talk to about important things—a proxy for social isolation. These rates are low across all coverage/income groups. When looking at specific age groups, however, younger (age 65-74) dual eligible beneficiaries are particularly likely to report not having someone to talk to (12%, versus 5% for seniors without Medicaid in the same age range) (Table 2). The higher rate among this group may indicate barriers to being integrated into the community and a need for more social interaction for this population.

Housing Type and Condition

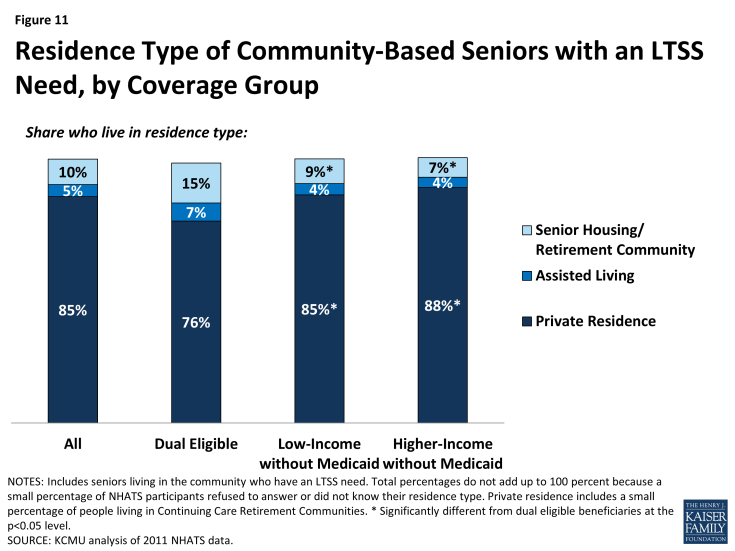

People who live in assisted living or senior housing/retirement communities may have access to more social or supportive services than those who do not live in such places. Overall, the majority (85%) of seniors with an LTSS need live in a private residence, versus an assisted living facility or senior housing/retirement community. However, dual eligible beneficiaries are less likely than seniors without Medicaid to live in a private residence and are more likely to live in senior housing or a retirement community (Figure 11), perhaps reflecting a greater level of need among dual eligible beneficiaries. These differences decrease at older ages (Table 2).

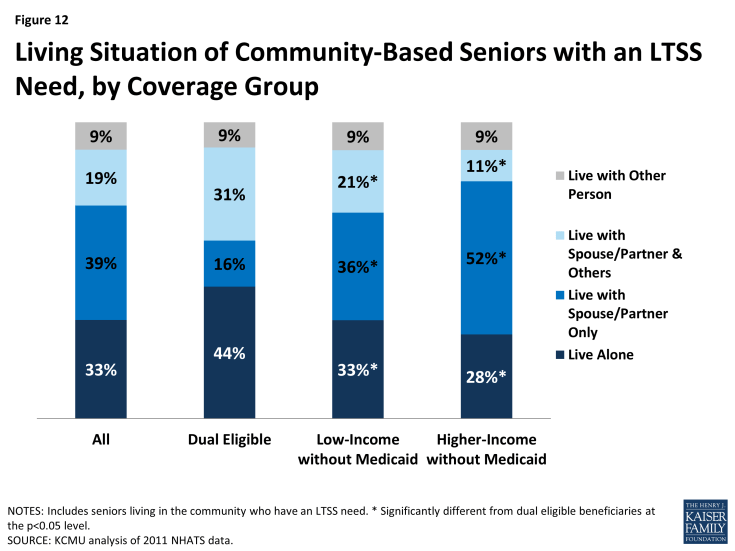

In addition, dual eligible beneficiaries with LTSS needs are more likely than seniors without Medicaid to live alone (Figure 12). This pattern holds for those ages 65 to 84, but differences decrease at older ages (Table 2). Notably, much of the low-income LTSS population without Medicaid lives alone. While people who live alone but have Medicaid coverage may receive personal care services to help them with day-to-day tasks, those who live alone, need LTSS, and do not have Medicaid must either pay for help out-of-pocket or rely on someone to come to their home daily to help them. Some people with LTSS needs live with someone else, in addition to a spouse or partner, perhaps because they select living arrangements that enable them to receive assistance from extended family or friends. Dual eligible beneficiaries are more likely than seniors without Medicaid to live with someone besides a spouse or partner, though many low-income seniors without Medicaid also have such living arrangements.

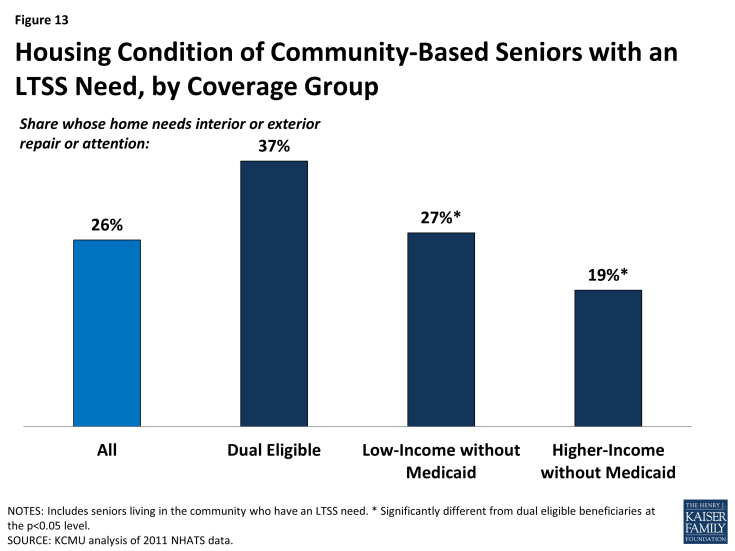

Further, among all seniors with an LTSS need, many live in a home that needs repair to the interior or exterior (26%). These repair needs may include minor conditions (e.g., flaking paint, a broken lamp) or more serious conditions (e.g., pests, tripping hazards) that pose a health hazard. Poor housing conditions may reflect the occupant’s limited income or ability to keep up on repairs, but a growing body of evidence indicates that these conditions can also have a deleterious effect on overall health and functioning.13 Thus, housing conditions may represent a challenge for programs and individuals trying to serve the population with LTSS needs, particularly since such repairs are not covered by Medicaid despite their impact on health. Dual eligible beneficiaries are more likely than seniors without Medicaid to live in a residence in need of interior or exterior repairs (Figure 13). Among older seniors (ages 85 and older), fewer differences in housing conditions are found across income groups, with low-income seniors without Medicaid as likely as dual eligible beneficiaries to live in a residence that needs repair (Table 2).

Conclusion and Policy Implications

Understanding the community-based population of seniors with LTSS needs is particularly important for designing effective systems to serve their needs. This population is at high risk for needing institutional care, which can be costly and is not the preferred site of care for most people. In addition, people in the community who need LTSS may not be linked to services or programs to meet their needs, placing them at risk of developing more extensive, and costly, needs over time. These outcomes are particularly likely for low-income seniors who do not have Medicaid, as they likely lack other coverage for LTSS and have limited resources to purchase these services. Should the low-income population without Medicaid reach the point where they need institutional care, many would likely become eligible for Medicaid.

Medicaid currently plays an important role in helping people with LTSS needs maintain health and functioning in the community. Because many dual eligible beneficiaries qualify for Medicaid as a result of a disability, high medical expenses, or a need for LTSS, rates of LTSS need are particularly high among seniors with Medicaid. Further, Medicaid seniors with LTSS needs are in worse overall physical or mental health than other seniors, indicating that Medicaid is serving the LTSS needs of a population with particularly complex health, social, and environmental needs.

The high level of LTSS need among Medicaid beneficiaries has implications for how to best deliver services to these seniors. This analysis shows high rates of comorbid physical and mental health problems among dual eligible beneficiaries with LTSS needs; it also finds a need for social supports such as efforts to improve housing conditions, reduce fall risk, and, in some cases, address social isolation. Delivery system reform initiatives seeking to better coordinate care across the domains of medical and LTSS and to integrate physical and behavioral health services could allow these beneficiaries’ needs to be met in a more holistic manner while potentially improving health outcomes and lowering costs. As of October 2014, 19 states had waivers to operate capitated managed long-term services and supports programs, most of which require beneficiaries to enroll in a Medicaid managed care organization to receive services, and as of July 2015, 12 states were implementing demonstrations seeking to better integrate services and align financing for dual eligible beneficiaries. Many of these programs aim to increase access to community-based services, and most integrate LTSS with acute and primary care as well as behavioral health services.14 Work is ongoing to measure how well these programs are meeting their goals and the needs of beneficiaries.15

States can select from among a variety of optional services to meet Medicaid beneficiaries’ LTSS needs, many of which allow beneficiaries to self-direct their services by selecting their personal care provider and/or administering their services budget. In recent years, new and expanded options to provide Medicaid LTSS have become available, although some programs are time-limited and set to expire.16 For example, the Affordable Care Act provides new Medicaid state plan options, with enhanced federal funding, for states to cover attendant care services and supports through the Community First Choice program and health home services to improve care coordination for beneficiaries with chronic conditions.17 As of July, 2015, five states had adopted the Community First Choice option,18 and as of June, 2015, 19 states had adopted the Medicaid health homes option.19 States have the flexibility to choose among various optional Medicaid services to design programs that best meet the needs of beneficiaries, and a better understanding of the characteristics of this population can assist those efforts.

In addition, the complexity of needs among the Medicaid population may indicate a role for LTSS to prevent deterioration in health status that could result in more costly long-term institutional care. With dual eligible beneficiaries more likely to live alone, these seniors may have less access to natural supports (such as a family caregiver) that could delay the need for formal LTSS. At the same time, supports may be needed to address the social determinants of health. For example, many dual eligible beneficiaries with LTSS needs live in a home in need of repairs. Investments to remediate these conditions, such as pests or tripping hazards, while not medical in nature, might help to avoid future health care costs arising from injuries or medical exacerbations stemming from these conditions if they remain unaddressed. While Medicaid does not cover home repairs, states may encourage their Medicaid managed care organizations to offer medically appropriate alternative services as cost-effective substitutes in lieu of services covered under the Medicaid state plan.20

While Medicaid is serving many seniors with LTSS needs, many low-income seniors who do not have Medicaid also have LTSS needs. This population still has notable rates of physical and mental health comorbidity, and many live in housing situations that may make it difficult to meet their needs in addition to lacking financial resources to pay for care out-of-pocket. Providing LTSS to meet this population’s needs may be cost-effective over the long-term as unmet needs may worsen and require more costly services to address in the future. In the absence of other public or private sources of LTSS coverage, Medicaid remains the nation’s primary payer for these services. States have a number of options to expand Medicaid eligibility to offer services to those in need of LTSS where medically necessary. For example, the Affordable Care Act expanded the § 1915(i) state plan option to create a new Medicaid eligibility pathway, including access to home and community-based services.21 Through this option, states can choose to cover (1) people who are not otherwise eligible for Medicaid with income up to 150 percent of the federal poverty level and no resource limit and/or (2) people who would be eligible for Medicaid under an existing waiver with income below 300 percent of the SSI federal benefit rate. Importantly, the § 1915(i) option enables states to offer home and community-based LTSS to beneficiaries who meet state-established functional eligibility criteria that are less restrictive than the state’s institutional level of care criteria. This allows states to offer home and community-based services as a preventive measure, before a person’s needs deteriorate to the point where institutional care is required. As of July 2015, 17 states had adopted the § 1915(i) option.22

States also have flexibility to set financial and functional eligibility criteria for Medicaid home and community-based waiver programs. At state option, these criteria may be more restrictive than the criteria used to qualify for Medicaid-funded nursing facility services.23 Limiting access to community-based services in this way can create a bias toward institutional care and barriers to returning to the community once the more restrictive waiver eligibility criteria are met. Even though community-based care may be less expensive than comparable institutional care, people who move into nursing facilities are likely to lose their community-based housing and other resources and connections that can help support their functioning in the community.

In addition, not all people who qualify for Medicaid home and community-based waivers receive those services. Unlike nursing facility services, which must be provided to beneficiaries if eligible, states can limit waiver enrollment. Enrollment caps can result in waiting lists for Medicaid-funded community-based services. Waiting list length varies by state and within states by waiver population. In 2013, there were over 27,000 people waiting for Medicaid waiver services targeted to seniors, with an average wait time of 13 months, and over 127,000 people waiting for waiver services targeted to seniors and non-elderly people with physical disabilities, with an average wait time of 10 months.24 While many people waiting for Medicaid waiver services are presently living in the community, their unmet LTSS needs may put them at risk of institutionalization and/or requiring more costly services in the future.

Looking ahead, state and federal policymakers and other stakeholders will be challenged to meet the growing need for LTSS to support seniors living in the community in a way that accommodates diverse needs, ensures care quality, and manages costs. Insight into the socio-demographic and health status characteristics of these seniors, especially dual eligible beneficiaries who rely on Medicaid for their LTSS needs and how they may be similar to or different from other seniors with LTSS needs, can lead to increased understanding about how to optimize policies to support these populations.