How ACA Marketplace Premiums Measure Up to Expectations

Premium increases in the health insurance marketplaces created under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) will likely be higher in 2017 than in recent years. While premiums generally go up every year as the underlying cost of care rises, there are a number of reasons to expect faster growth this coming year, including the expiration of the ACA’s temporary reinsurance program at the end of 2016 and miscalculations by many insurers about how much health care enrollees would use.

Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of proposed rates in states that make the information publicly-available shows an average premium increase in the benchmark second-lowest-cost Silver plan in 17 major cities of 9% in 2017, compared to an average increase of 2% in these cities in 2016. The second-lowest-cost Silver plan is a popular choice in this market, and is particularly significant because it is the benchmark for federal subsidies provided to low- and middle-income enrollees. It therefore helps determine how much these subsidies cost the government.

Bigger rate hikes coming in 2017 raise the question of how premiums compare to what was expected when the ACA was considered by Congress. At the time, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that the law would modestly reduce the budget deficit over a ten-year period, taking into account new expenses, new taxes, and savings in existing government health programs. How actual marketplace premiums compare to what CBO expected in doing those budget projections is an important factor in determining whether the ACA continues to be on track to reducing the deficit.

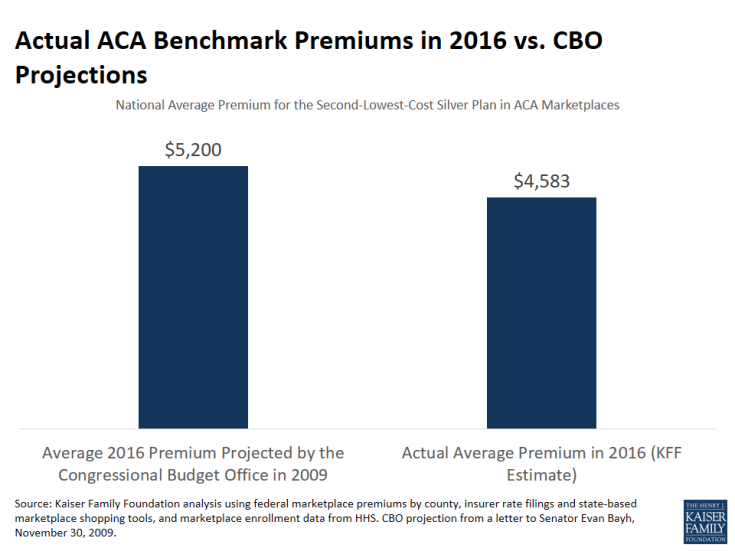

In late 2009, as the debate over the ACA began before the U.S. Senate, CBO (along with the Joint Committee on Taxation) released an analysis of how premiums in the individual insurance market would change under the law. CBO projected that the average nationwide premium for a benchmark plan (i.e., the second-lowest-cost Silver plan) would be about $5,200 for single coverage in 2016 (the only year for which CBO provided projections).

We estimate that the actual average benchmark premium in the ACA marketplaces in 2016 is $4,583, or 12% below what CBO originally projected. Even if benchmark premiums rise by 9% in 2017, as suggested by our analysis of major metropolitan areas, they would on average remain below what CBO estimated in its projections of the cost of expanding coverage under the ACA.

There are a variety of factors that may explain why premiums are lower than projected, including the persistent slowdown in health cost growth and strong competition in the marketplaces in much of the country. Even in areas with a handful of plans, insurers face competitive pressure to offer low-cost options as the ACA’s market rules allow enrollees to more easily shop for coverage and the subsidy calculation adds financial incentive to do so. These incentives have led some insurers participating in the marketplaces to narrow their provider networks to enable lower premiums.

Lower-than-expected premiums are also the result of underpricing by many insurers, which led to them taking larger premium increases in 2016 and 2017. There are good reasons to believe that these bigger premium increases are a one-time market correction rather than a trend, as insurers are now able to make use of better data on the claims experience of their enrollees to adjust their premiums to the proper level and as the temporary reinsurance program sunsets. However, there is no guarantee that insurers currently losing money on marketplace business will be able to stem those losses with premium increases. Also, recent exits from the marketplaces and the individual insurance market by some insurers could diminish competition.

While subsidies cushion premium increases for the 82% of marketplace enrollees who receive them, consumers may have to switch plans to obtain the full extent of that protection. During open enrollment for 2016, 43% of returning enrollees switched plans. If that high degree of plan switching does not persist, though, premium increases could lead healthier enrollees – including those who are not eligible for subsidies – to drop coverage, in turn leading to the need for additional premium increases in coming years. Since insurance pools operate at the state level, experience could vary from state to state.

So far, however, the fact that premiums are coming in lower than expected when the ACA passed suggests some cause for optimism.

Methods

To estimate the average benchmark premium in 2016, we did the following:

- Determined the premium for the second-lowest-cost Silver plan for a 40 year-old in each county nationwide using the QHP landscape dataset for the federal marketplace and in each rating area using rate filings or shopping tools for state-based marketplaces.

- Calculated a national average benchmark premium for a 40 year-old weighted by core-based statistical area (CBSA) population.

- Estimated the average benchmark premium across all ages using the standard factors for how premiums vary by age and the national distribution of marketplace plan selections by designated age categories (including the small number of enrollees under age 18). We assumed that enrollees were distributed equally within age categories. Six states do not use the standard age factors, but that should not materially affect the national average premium calculation.

The Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation within U.S. Department of Health and Human Services reported that the average benchmark premium in 2016 for a 27 year-old in states participating in the federal marketplace is $240 per month. Our method produces a similar estimate for the average benchmark premium for a 27 year-old nationwide (including state-based marketplaces) at $245 per month. A recent blog post in Health Affairs by researchers at the Brookings Institution also examined how CBO’s premium estimates have been lowered since 2009.