Opportunities and Barriers for Telemedicine in the U.S. During the COVID-19 Emergency and Beyond

| Key Takeaways |

|

Introduction

As clinicians seek new ways to serve patients and stem the rapid spread of the novel coronavirus in the United States, policymakers and insurers have looked to telemedicine or telehealth to provide care to patients in their homes. At a time when many people in the U.S. are under shelter in place orders, this approach to care allows patients to maintain social distancing, reduce their risk of exposure to the novel coronavirus and potentially avoid overburdening emergency departments and urgent care centers at this time. After many years of slow growth, telemedicine use has exploded across the nation in a few short weeks. The telemedicine landscape is complex, with many moving pieces as different players respond to COVID-19. The federal government has taken actions to broaden and facilitate the use of telemedicine, particularly though Medicare. States, health systems, and insurance carriers have also moved with unprecedented speed to shift many visits that were previously done in person to a telemedicine platform. This brief presents some of the many policy changes that have taken place in the field of telehealth by the federal government, state governments, commercial insurers and health systems in just the few short weeks since the COVID-19 outbreak hit the U.S. We highlight key considerations in achieving widespread implementation of telemedicine services during this pandemic and beyond, including easing of telemedicine regulations, broadening insurance coverage, strengthening telecommunications infrastructure, and patient facing issues like connectivity and quality of care.

What is telemedicine?

While varied definitions for telemedicine or telehealth exist, it is commonly defined as the remote provision of health care services using technology to exchange information for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease. Telemedicine is usually defined narrowly by insurers to include technologies like live videoconference and remote patient monitoring, while telehealth is often defined more broadly, to include basic telecommunication tools, as simple as phone calls, text messages, emails, or more sophisticated online health portals that allow patients to communicate with their providers. However, telehealth and telemedicine are often used interchangeably.

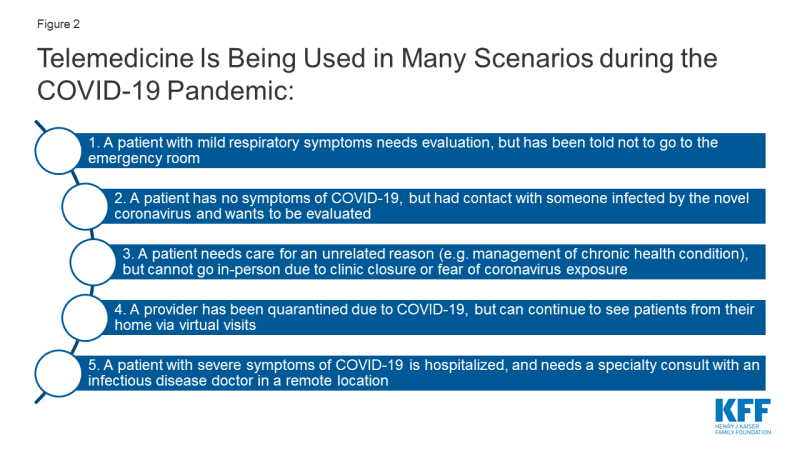

Telemedicine can enable providers to deliver health services to patients at remote locations, by conducting “virtual visits” via videoconference or phone (Figure 1). During a telemedicine visit, a patient may see providers from their usual source of care, like Stanford Health, Kaiser Permanente, or Mount Sinai, or they may interact with providers employed by a stand-alone telemedicine platform like Amwell or Virtuwell. Telemedicine can also enable remote interactions and consultations between providers.

Figure 1: Telemedicine Can Facilitate a Broad Range of Interactions Using Different Devices and Modalities

How widespread was telemedicine use before COVID-19?

Before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, utilization of telemedicine in the U.S. was minimal. Telemedicine growth has been limited by lack of uniform coverage policies across insurers and states, and hurdles to establishing telemedicine in health systems (e.g. high startup costs, workflow reconfiguration, clinician buy-in, patient interest). The Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker analyzed a sample of health benefit claims from the IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database; among enrollees in large employer health plans with an outpatient service, 2.4% had utilized at least one telehealth service in 2018 (up from 0.8% in 2016). Similarly, utilization of telemedicine by traditional Medicare and Medicaid and beneficiaries enrolled in managed care plans had been trending upward, but remained low.

How is telemedicine being used during the COVID-19 pandemic?

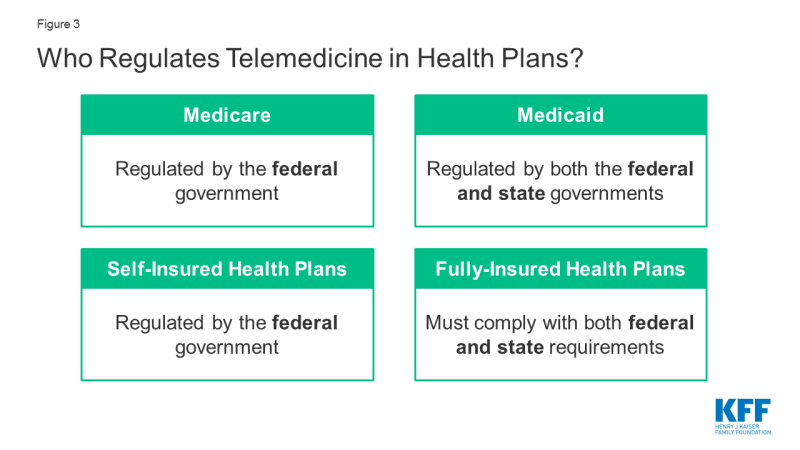

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there are multiple scenarios in which patients and providers are utilizing telemedicine to enable remote evaluations between a patient and a provider, while respecting social distancing. (Figure 2). Use of “virtual visits” via phone or videoconference can address non-urgent care or routine management of medical or psychiatric conditions, while online or app-based questionnaires can facilitate COVID-19 screening to determine the need for in-person care.

Many hospitals have instructed patients with suspected coronavirus symptoms or exposure to call their doctors or turn to telemedicine first, before showing up to the emergency room or urgent care visit. The Cleveland Clinic, University of Washington (UW), NYU Langone, Oregon Health Sciences University (OHSU), Intermountain Health Care, Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), and Rush University Medical Center are all advising patients with suspected coronavirus to start by using a virtual visit or online screening, rather than presenting to an emergency room for testing. This is in line with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) encouragement that those who are mildly ill should call their doctors before seeking in-person care. For patients who are having more severe symptoms (e.g. difficulty breathing) or with complex comorbidities, evaluation from their home via telemedicine may not be appropriate, as in-person care intervention may be needed.

What measures have been taken so far to expand telehealth access in the U.S.?

In response to the novel coronavirus, demand for telemedicine is rapidly increasing. Telemedicine, what was once a niche model of health care delivery, is now breaking into the mainstream in response to the COVID-19 crisis. In China, telemedicine platform JD Health saw a tenfold increase in their services during the outbreak and is now providing nearly 2 million online visits per month. In the U.S., existing telemedicine platforms like Amwell and UPMC’s virtual urgent care have reported rapid increases in their utilization. A recent poll found 23% of adults have used telehealth services in light of the COVID-19 pandemic.

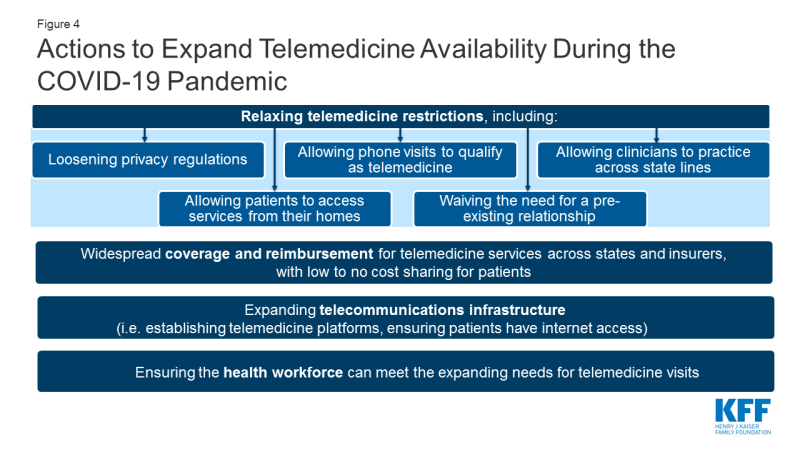

There are a myriad of telemedicine laws and regulations determine who can deliver which telemedicine services to whom, in what location, in what fashion, and how they will be reimbursed. The federal government regulates reimbursement and coverage of telemedicine for Medicare and self-insured plans, while Medicaid and fully-insured private plans are largely regulated on a state-by-state basis (Figure 3). This complexity in the regulatory framework for telemedicine creates challenges for patients in knowing what services are covered, and for providers in knowing what regulations to abide by.

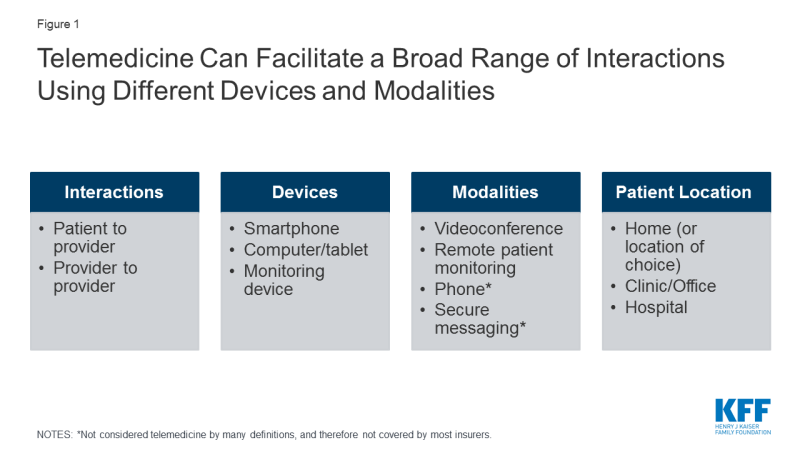

As the COVID-19 pandemic evolves, so too are the emergency policies regarding telemedicine. The federal government, some states, and some health insurance carriers are trying to enable more telemedicine visits to be permitted and paid for. It is important to note that even when the federal government announces loosening of telemedicine restrictions that states have their own regulations and laws that shape coverage in state-regulated (fully insured) insurance plans and Medicaid. And even when regulations are temporarily lifted to facilitate telemedicine, health systems and patients will have their own challenges in implementing and accessing these services. While many of the telemedicine regulations have been temporarily relaxed, for telemedicine to be more broadly accessible to patients in the U.S. over the long term, several actions would need to happen (Figure 4). Next, we outline what changes have been made to telehealth policy and implementation by the federal government, state governments, commercial insurers and health systems in response to the COVID-19 emergency, as well as what gaps remain.

Federal Changes to Telehealth Policy

The federal government dictates several facets of telehealth policy, including nationwide patient privacy laws (e.g. HIPAA), federal prescribing laws for controlled substances, grant funding for telehealth initiatives and Medicare coverage of telehealth. In response to the COVID-19 emergency to make telemedicine more widely available, the federal government has taken action in all these domains.

HIPAA

Typically telemedicine platforms are required to comply with regulations under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), which health organizations and providers must follow to protect patient privacy and health information. However, on March 17, 2020 the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued an announcement stating that, “Effective immediately… [HHS] will exercise enforcement discretion and will waive potential penalties for HIPAA violations against health care providers that serve patients in good faith through everyday communications technologies during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency.” This now allows widely accessible services like FaceTime or Skype to be used to telemedicine purposes, even if the service is not related to COVID-19. Potential concerns to this approach include the possibility that protected health information (PHI) that is discussed or sent over a non-HIPAA compliant platform may be accessed, shared or even sold by these platforms. The National Consortium of Telehealth Resource Centers (NCTRC) currently urges health centers to sign a Business Associate Agreement (BAA) with their chosen platform, to agree that the data exchanged are safeguarded. In addition to HIPAA, many states have their own laws and regulations to protect patient health information. Loosening enforcement of HIPAA will likely not impact state level regulations, meaning states would need to lift or loosen their own health information laws. Some states (e.g. CA, ME, MD, NM, ND, UT) have issued guidance to relax state-specific privacy standards for telehealth during the state of emergency.

Federal oversight of Controlled substances

Under the Controlled Substances Act, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) normally requires an in-person evaluation before a provider can prescribe a controlled substance, limiting telemedicine’s use for e-prescribing of controlled substances without a prior in-person patient-provider relationship. However, during a state of national emergency, there are exceptions to this rule. For the duration of the COVID-19 public health emergency, DEA-registered providers can now use telemedicine to issue prescriptions for controlled substances to patients without an in-person evaluation, if they meet certain conditions. One of these conditions is that provider must still comply with state laws; many states have their own laws regulating telemedicine and controlled substances, which federal changes would not affect.

Medicare

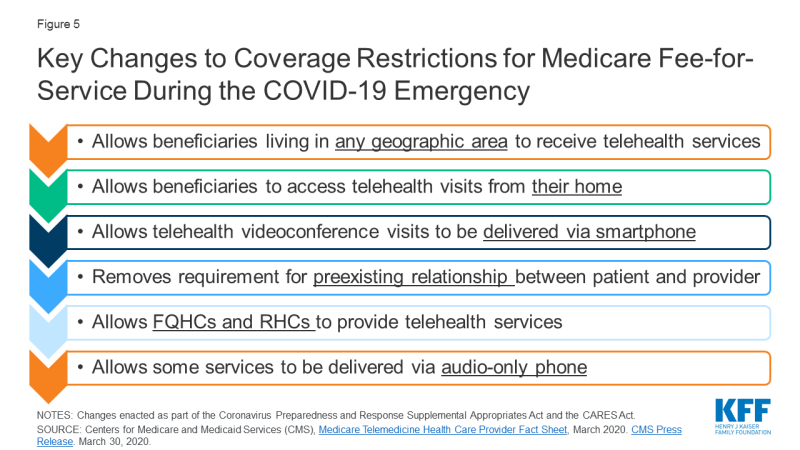

Changes to Traditional Medicare: Based on new waiver authority included in the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act (and amended by the CARES Act), the HHS Secretary has waived certain restrictions on Medicare coverage of telehealth services for traditional fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare beneficiaries during the coronavirus public health emergency (first issued on January 31, 2020, and renewed on April 21, 2020). The waiver does the following: lifts the requirement that beneficiaries must live in rural areas in order to receive telehealth services, meaning beneficiaries in any geographic area could receive telehealth services; allows the patient’s home to qualify as an “originating site” from which they can access telehealth visits; allows telehealth visits to be delivered via smartphone with real-time audio/video interactive capabilities in lieu of other equipment; and removes the requirement that providers of telehealth services have treated the beneficiary in the last three years. A separate provision in the CARES Act allows federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) and rural health clinics (RHCs) to serve as “distant site” providers, and provide telehealth services to Medicare beneficiaries during the COVID-19 emergency period (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Key Changes to Coverage Restrictions for Medicare Fee-for-Service During the COVID-19 Emergency

CMS has also expanded access to the types of services that made be provided via audio-only telephones. In a March 2020 Interim Final Rule, CMS stated that it would allow providers to “evaluate beneficiaries who have audio phones only.” In a subsequent announcement, CMS broadened this to include behavioral health services and patient education services, but still not the full range of telehealth services that can be provided using two-way audio-video connection. This limits telehealth’s reach for Medicare beneficiaries without access to smartphones or other video communications. Other modifications to telehealth availability in response to the COVID-19 emergency include allowing both home health agencies and hospice providers to provide some services via telehealth, and allowing certain required face-to-face visits between providers and home dialysis and hospice patients to be conducted via telehealth. Additionally, CMS is temporarily waiving the Medicare requirement that providers be licensed in the state they are delivering telemedicine services when practicing across state lines, if a list of conditions are met. This change however, does not exempt providers from state licensure requirements (see section below on state licensing actions). Medicare is also temporarily expanding the types of providers who may provide telehealth services.

Importantly, these expanded telehealth services under Medicare are not limited to COVID-19 related services, rather they are available to patients regardless of diagnosis and can be used for regular office visits, mental health counseling, and preventive health screenings. Separate from the time-limited expanded availability of telehealth visits, traditional Medicare also covers brief, “virtual check-ins” via telephone or captured video image, and E-visits, for all beneficiaries. These visits are more limited in scope than a full telehealth visit.

Medicare covers all types of telehealth services under Part B, so beneficiaries in traditional Medicare who use these benefits are subject to the Part B deductible of $198 in 2020 and 20 percent coinsurance, although many beneficiaries have some source of supplemental coverage that helps pay their share of costs. However, the HHS Office of Inspector General is providing flexibility for providers to reduce or waive cost sharing for telehealth visits during the COVID-19 public health emergency.

Changes to Medicare Advantage: Medicare Advantage plans have been able to offer additional telehealth benefits not covered by traditional Medicare and have flexibility to waive certain requirements with regard to coverage and cost sharing in cases of disaster or emergency, such as the COVID-19 outbreak. In response to COVID-19, CMS has advised plans that they may waive or reduce cost sharing for telehealth services, as long as plans do this uniformly for all similarly situated enrollees. This guidance, however, is voluntary and plans will vary in their responses to this new flexibility.

Federal Funding for telehealth

The newly passed Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act includes additional funding to the Telehealth Network Grant Program (TNGP). This program currently awards a total of $8.7 million a year for telehealth technologies used in rural areas and medically underserved areas. The act strikes the current funds, and replaces it with $29 million for five years, starting in 2021. The bill also ends funding for the Telehealth Resource Center (TRC) Grant Program, which is currently funding TRCs at roughly $4.6 million a year for four years, since 2017.

State Changes to Telehealth Policy

A significant portion of telehealth policy is decided by state governments. Each state has its own laws regarding provider licensing, patient consent for telehealth and online prescribing laws. Importantly, states also are in charge of deciding which telehealth services will be covered by their Medicaid program, and most states also have laws governing reimbursement for telemedicine in full-insured private plans. Changes to state level regulations in response to COVID-19 are described next.

Licensing laws

Normally, clinicians must be licensed to practice in states where they offer telemedicine services, and states regulate which health professionals are credentialed to practice in their state. For example, if a clinician is located in California, but is providing services remotely to a patient in Oregon via telemedicine, the provider must be licensed in Oregon, the state where the patient is located. Nine states require special licenses specific to telemedicine. Others participate in “compacts” that allow providers in participating states an expedited process to practice in other compact states. However, to address COVID-19, out of state clinicians may be needed to conduct virtual visits with patients in states with the highest burden of cases. This requires they be licensed to practice across state lines. Almost all states are moving to temporarily waive out of state licensing requirements, so that providers with equivalent licenses in other states can practice via telehealth. The Federation of State Medical Boards is tracking these updates, and finds that currently 49 states have issued waivers regarding licensure requirements during the COVID-19 emergency.

STate Specific Online prescrIbing laws

Most states require a patient-provider relationship be established before e-prescribing of medications. Many telemedicine platforms use an online health questionnaire to establish that relationship, but in at least 15 states, this method is considered inadequate. Instead, a physical exam would be required before prescribing, either in-person, by live-video, or by a referring physician, depending on the state. For patients who are now turning to telemedicine visits rather than their usual source of in-person care, clinicians in some states may face legal barriers to online prescribing medications if they do not already have a pre-existing relationship with the patient. Many states are issuing emergency orders to remove in-person requirements before engaging in telehealth, for the duration of the public health emergency (e.g. AK, AZ, AR, DE, HI, IA, KS, KY, LA, MD, MS, MT, OH, OK, SD).

Consent Laws

Thirty-eight states and DC require providers to obtain and document informed consent from patients before engaging in a telehealth visit. In some states, this applies only to Medicaid beneficiaries, but in others this applies to all telehealth encounters regardless of payor. In most states, verbal consent is allowed, but in a minority of states, consent must be obtained in writing. In response to COVID-19, some state Medicaid programs that would normally require written consent have waived this requirement; for example, providers caring for Medicaid beneficiaries in Alabama, Delaware, Georgia, and Maine can now obtain verbal consent for telemedicine, rather than having the patient sign a written consent form.

Private Insurers and Employer Plans

As of Fall 2019, 41 states and D.C. had laws governing reimbursement for telemedicine services in fully-insured private plans, but private insurer laws enacted by states vary widely. In approximately half of states, if telemedicine services are shown to be medically necessary and meet the same standards of care as in-person services, state-regulated private plans must cover telemedicine services if they would normally cover the service in-person, called “service parity.” However, fewer states require “payment parity,” meaning telemedicine services to be reimbursed at the same rate as equivalent in-person services. CCHP finds only 6 states (CA, DE, GA, HI, MN, NM) that required payment parity prior to COVID-19, while a KFF analysis of telehealth laws suggests an additional 4 states followed payment parity as well (AR, CO, KY, NJ). In the remaining states, telemedicine is typically reimbursed at lower rates than equivalent in-person care. In response to COVID-19, more and more states are enacting service and payment parity requirements for fully-insured private plans. For example, at least 16 states are requiring payment parity for telehealth during the public health emergency.

In contrast to fully-insured health plans which must comply with both federal and state requirements, self-insured health plans are regulated by the federal government through the Department of Labor. These plans may cover telemedicine, but each plan can choose to cover these services or not. Prior analysis shows that the majority of large employer plans, including those that are self-insured, cover some telemedicine services.

Medicaid

Telehealth Policy Before the COVID-19 Emergency: The use of telehealth in the Medicaid program has grown as states have sought to address barriers to care including insufficient provider supply (especially specialists), transportation barriers, and rural access challenges. Historically, states have had broad flexibility to determine whether to cover telehealth/telemedicine, which services to cover, geographic regions telehealth may be used, and how to reimburse providers for these services. Prior to COVID-19, all states and DC provided some coverage of telehealth in Medicaid FFS but the definition and scope of coverage varied from state to state. The most commonly covered modality of telehealth was live video. Few states permitted “audio-only” telephone care to qualify as a telehealth service. Additionally, only 19 state FFS Medicaid programs allowed patient’s to access telemedicine from their homes (e.g. home was not an eligible “originating site”), limiting telemedicine’s reach for many low income people. Of note, state telehealth policies may differ between Medicaid FFS and managed care, an important distinction given most Medicaid beneficiaries are now in managed care plans. A study of Medicaid claims data showed beneficiaries enrolled in Medicaid managed care plans were more likely than those in FFS programs to use telemedicine.

Policy Changes in Response to COVID-19: In response to the COVID-19 outbreak, CMS issued guidance reiterating states can use existing flexibility to provide coverage for telehealth services: “States have broad flexibility to cover telehealth through Medicaid, including the methods of communication (such as telephonic, video technology commonly available on smart phones and other devices) to use.” They clarify, “No federal approval is needed for state Medicaid programs to reimburse providers for telehealth services in the same manner or at the same rate that states pay for face-to-face services.” The FAQ guidance also discusses how telehealth and telephonic services can be covered for FQHCs and rural health centers (RHCs) and under managed care contracts, if states choose to do so.

Almost all states are issuing emergency policies in response to the COVID-19 outbreak to make telehealth services more widely available in their Medicaid FFS programs and/or through Medicaid managed care plans. Importantly, most states are newly allowing both FFS and managed care Medicaid beneficiaries to access services from their home, and most are directing Medicaid plans to allow for reimbursement for some telephone evaluations. Many states are newly allowing FQHCs and RHCs to serve as distant site providers, and expanding which professions qualify as eligible to provide telehealth services through Medicaid.

States are also using 1915(c) Appendix K waivers to enable the provision of home and community-based services (HCBS) remotely by telehealth for people with disabilities and/or long-term care needs. Using Section 1135 waivers all 50 states and DC are relaxing licensing laws, many allowing out-of-state providers with equivalent licensing to practice in their state. Additionally, Medicaid programs in 46 states and DC have issued guidance to expand coverage or access to telehealth during this crisis, while 38 states and DC have granted payment parity for at least some telehealth services as of May 5, 2020. Despite most states moving to expand Medicaid coverage of telehealth services, these changes are not uniform across states, and barriers to implementing and accessing telehealth more broadly are likely to remain during this emergency. KFF is tracking other state Medicaid actions to address COVID-19, found here.

Voluntary Changes to Telehealth by Commercial Insurers

When not mandated by the state, private insurers are free to decide which telehealth services their plans will cover. Therefore, changes to telehealth benefits as a result of COVID-19 vary by insurer. Several major health insurance companies have voluntarily expanded telehealth coverage for fully-insured members (Appendix). Many insurers are reducing or eliminating cost sharing for telemedicine, for a limited period of time. For some plans this applies only to telehealth visits related to COVID-19, while for others this applies to any health indication. Some insurers are expanding their coverage of telehealth benefits, allowing more services, patient locations (e.g. home) and modalities (e.g. phone) to qualify for coverage. To make these services more readily accessible to patients, some insurers are working to increase their numbers of in-network telehealth providers within their existing networks of care, while others are contracting with specific telehealth vendors to provide these services. For example, First Choice Health will waive cost-sharing for telehealth if care is delivered via the 98point6 platform, and Oscar will do so if delivered by the Doctor on Call service. Florida Blue and Prominence Health Plan will waive copays for telehealth if using the Teladoc platform (Appendix). Therefore, patients may not be able to talk to their usual providers, if restricted to certain telehealth platforms by their insurance provider. Insurers responding to the novel coronavirus allow self-insured plans greater flexibility compared to fully insured plans in implementing these new changes, providing an opt-out or opt-in option.

Health System Changes to Telehealth

Prior to the start of the COVID-19 outbreak, more than 50 U.S. health systems already had telemedicine programs in place, including large health centers like Cleveland Clinic, Mount Sinai, Jefferson Health, Providence, and Kaiser Permanente. Meanwhile an estimated 15% of physicians had used telemedicine to facilitate interactions with their patients. However, many health systems did not have existing telemedicine infrastructure, and many providers are novices to providing care through telemedicine. As health systems and smaller practices implement or ramp up use of telemedicine in response to this crisis, there are many provider facing and patient facing considerations to address. Health systems will need to decide whether to invest in telemedicine infrastructure for long-term use, or if they are looking for shorter term, potentially cheaper, solutions solely to respond to this acute crisis.

Provider Facing Considerations

Investing in Telecommunications Infrastructure

For those wishing to initiate a telemedicine program before the COVID-19 emergency, significant financial and personnel investment was typically required. Costs included hiring programmers to create a telemedicine platform, ideally one that integrates into an existing electronic health record, protects patient privacy, and can charge for visits if needed. Alternatively, health systems could contract with existing telemedicine platforms to provide these services. In a 2019 study by Definitive Healthcare, many outpatient practices reported not investing in telehealth due to these financial barriers.

With new telehealth flexibility and relaxation of privacy laws in response to COVID-19, some of these financial hurdles may be lessened. For example, providers can now use phone calls, or affordable technologies like Facetime and Zoom, for many patient encounters, at least for the time being. If and when the regulatory environment around telehealth and HIPAA becomes more stringent, however, providers will need to decide whether to invest in more robust telemedicine platforms to continue to provide these services. This may be beyond what is feasible for many smaller practices, or less-resourced clinics.

During the COVID-19 crisis, ensuring reliable internet connection, and sound and video quality on both the patient and provider end remains important for any telehealth interaction. One concern is that resource limited health organizations may not have sufficient bandwidth to achieve this. During the current outbreak, many telemedicine platforms are experiencing high volumes of patients trying to access care online which has resulted in IT crashes and long wait times to obtain a virtual appointment in some systems. Investing in IT personnel may be necessary to troubleshoot problems with telehealth visits.

Workflow and Training

Implementing new telemedicine initiatives in response to COVID-19 oftentimes requires a redesign of longstanding clinical care models. With expanding use of telemedicine in clinical settings, health systems need to decide which providers they will divert to phone lines and/or video visits and how to manage their patient flow, while still ensuring enough staff to manage in-person care. This means some telemedicine platforms may need to hire more clinicians in order to keep up with demand. While larger health systems may have the financial resources to do this, smaller and more rural practices may be stretched thin as it is. Whether it be doctors, advance practice clinicians like nurse practitioners and physicians’ assistants, or registered nurses who facilitate telemedicine interactions, all will need to be trained on telemedicine technologies, requiring additional time and resources.

Malpractice and Liability Insurance

Clinicians must ensure their malpractice or liability insurance covers telemedicine, and if needed, that it covers services provided across state lines. Hawaii is the only state to require malpractice carriers to offer telemedicine coverage, and insurance premiums may be higher if covering telemedicine. During the COVID-19 outbreak, there are many clinicians who are first-time users of telemedicine, who must ensure they are covered before providing services.

Patient Facing Considerations

Access to Technology

Access to telemedicine may be particularly challenging for low-income patients and patients in rural areas, who may not have reliable access to internet through smartphones or computers. A KFF study showed that in 2017, sizable shares of non-elderly adults with Medicaid reported they had never used a computer (26%), did not use the internet (25%) and did not use email (40%). Additionally, a study by the Harvard School of Public Health showed that 21% of rural Americans reported access to high-speed internet is a problem for them or their family. Telemedicine solutions may also be less feasible for seniors. Because older patients are at higher risk for severe symptoms of coronavirus and in general require more frequent primary care, they may benefit greatly from telehealth to reduce in-person risk of exposure. However, many seniors may not feel comfortable or be able to use these technologies. According to Pew Research Center, 27% of U.S. adults aged 65+ reported they did not use the internet in 2019. Based on the results of a March 2020 KFF Health Tracking Poll, nearly seven in 10 adults 65 and older (68%) say they have a computer, smart phone or tablet with internet access at home (compared to virtually all adults ages 30-49 and 85% of adults ages 50-64). However, this may not translate to widespread use of telehealth among older adults, particularly when Medicare’s expansion of telehealth services for people in traditional Medicare is at the moment limited to the duration of the public health emergency. While studies show some interest in telehealth among older individuals, concerns include perceived poorer quality of care, privacy issues and difficulty using technology.

Quality of Care

While use of telehealth has opened the door for patients to maintain access to care during this public health crisis, ensuring quality of care of telehealth visits is still important. There are some inherent differences to evaluating patients remotely from their homes compared to in-person. For patients with possible coronavirus infection, taking a thorough history via telemedicine is relatively straightforward, including reviewing symptoms, travel history and exposure history. However, taking important vital signs like a temperature and oxygen saturation proves challenging, particularly if the patient does not have a thermometer or pulse oximeter at home. Without specialized equipment, providers also cannot listen to a patient’s lungs to assess for signs of pneumonia. Further, currently almost all coronavirus testing is happening in person, although the FDA recently approved the first at-home test. While a limited telemedicine assessment may be adequate to determine if a patient needs to present to an emergency room/urgent care or for testing, there are the limitations of telemedicine care for this purpose.

For patients utilizing telemedicine during the COVID-19 emergency for non-respiratory complaints, virtual evaluation may prove challenging as well. For example, if a pregnant person wishes to use telemedicine for a prenatal care visit to reduce their virus exposure, monitoring routine measurements like blood pressure, weight and fetal heart rate will prove challenging if not already set up to do so at home. If a patient needed to buy home monitoring equipment like a blood pressure cuff or a glucose monitor, it remains unclear if this would be paid for by the patient out of pocket, or by the health system.

What more could be done to expand and sustain access to telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond?

In response to the unprecedented pressure to expand services and control the transmission of the novel coronavirus, the federal government, many states governments and commercial insurers are expanding coverage of telemedicine and relaxing existing regulations. The federal government has focused on broadening telemedicine access for Medicare beneficiaries, and waiving enforcement of HIPAA to enable use of video platforms like Facetime and Skype. Many states have relaxed telemedicine written consent, licensing, and online prescribing laws, while expanding coverage in Medicaid and fully-insured private plans. Meanwhile, many health centers have rapidly redesigned their existing models of care to implement telemedicine.

While these unprecedented and swift measures have been taken to broaden telemedicine access during this pandemic, gaps in coverage and access to telemedicine remain. Coverage and reimbursement of telemedicine is still far from uniform between payors, and most changes to telehealth policy are temporary. If the U.S. wishes to invest in telemedicine over the longer term, more permanent measures may need to be taken. Avenues to consider to further expand telemedicine access include:

- Ensuring service parity and payment parity for telemedicine care as compared to in-person care, to help expand covered services for patients, and incentivize clinicians to provide this model of care

- Ensuring patients can access telemedicine services from their homes (home as “originating site”), to further enable social distancing practices

- Allowing use of audio-only phone for telemedicine visits, to help ensure access for patients who do not have live-video technology

- Investing in telecommunications infrastructure for less-resourced sites of care, and ensuring internet access to patients in rural areas. This may involve providing direct funding for health systems and smaller practices to implement telemedicine

There are potential trade-offs in loosening regulations on telemedicine, including privacy issues and quality of care. Depending on the insurer, some patients may be able to engage in telemedicine visits with their usual providers, while some may have to see providers from specific telemedicine vendors, outside of their usual source of care. This could create discrepancies in access and continuity of care. Additionally, expanding coverage of telemedicine may result in increasing health spending, if patients use telehealth in addition to in-person care, rather than as a substitute. With all these factors in mind, it will be up to policymakers, payors, and providers to determine if the changes made to telehealth policy in light of COVID-19 outweigh the potential concerns, if they should remain permanently, and if telemedicine helps enable accessible, quality health care.