As Pandemic-Era Policies End, Medicaid Programs Focus on Enrollee Access and Reducing Health Disparities Amid Future Uncertainties: Results from an Annual Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2024 and 2025

Pharmacy

Context

Drug Expenditures. Management of rising pharmacy costs continues to be a focus area at both the state and federal levels. Between FY 2017 and FY 2023, net Medicaid spending on prescription drugs (after rebates) grew by 72% and in FY 2023, prescription drugs accounted for approximately 6% of total Medicaid spending. Much of the spending growth in recent years has been attributed to new high-cost specialty drugs, including obesity drugs and emerging cell and gene therapies that treat, and sometimes cure, rare diseases but at a high cost to Medicaid and other payers.

State Level Controls. The federal Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP) requires states to cover nearly all FDA-approved drugs from rebating manufacturers, limiting states’ ability to control drug costs through restrictive formularies. Instead, states use an array of payment strategies and utilization controls to manage pharmacy expenditures, including preferred drug lists (PDLs), prior authorization, managed care pharmacy carve-outs, and value-based arrangements (VBAs) negotiated with individual pharmaceutical manufacturers that increase supplemental rebates or refund payments to the state if the drug does not perform as expected. States and MCOs may contract with external vendors like pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) to manage or administer the pharmacy benefit. PBMs may perform a variety of administrative and clinical services for Medicaid programs (e.g., developing a provider network, negotiating rebates with drug manufacturers, adjudicating claims, monitoring utilization, overseeing PDLs, etc.) and are used in both fee-for-service (FFS) and managed care settings. PBMs, however, have faced increased scrutiny in recent years as more states adopt reforms to increase transparency and improve oversight.

Federal Initiatives. As of January 1, 2024, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) lifted the cap on the total amount of statutory rebates that Medicaid could collect from manufacturers that raise drug prices substantially over time. Some manufacturers have responded by cutting prices or discontinuing drug products to avoid paying increased rebates which have implications for state rebate collections and PDLs. Further, the Inflation Reduction Act included a number of prescription drug reforms that primarily apply to Medicare. The Congressional Budget Office has predicted, however, that one of those provisions (the Medicare inflation rebate requirement) will interact with Medicaid, resulting in a net increase in Medicaid drug costs. A federal rule was also recently finalized aimed at increasing price transparency and established a voluntary model for states and manufacturers to increase access to cell and gene therapies for people with Medicaid. There have also been recent bills under consideration with Medicaid drug pricing provisions and potential implications for Medicaid drug spending.

Obesity Drugs. GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1) agonists have been used as a treatment for type 2 diabetes for over a decade and are covered by state Medicaid programs for that purpose. However, newer forms of these drugs, such as Wegovy and Zepbound, have gained widespread attention for their effectiveness as a treatment for obesity and are causing state Medicaid programs and other payers to re-evaluate their coverage policies for obesity drugs. Recent KFF analysis has found most large employer firms do not cover GLP-1 drugs for weight loss, coverage in ACA Marketplace plans remains limited, and coverage in Medicare is prohibited. In Medicaid, states must cover nearly all FDA-approved drugs for medically accepted indications; however, a long-standing statutory exception allows states to choose whether to cover weight-loss drugs under Medicaid for adults, leading to variation in coverage policies across states. All obesity drugs are covered for children under Medicaid’s Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit, though it is less clear how states are implementing and covering these services in practice. Almost 40% of adults and 26% of children with Medicaid have obesity, and expanding Medicaid coverage of these drugs could address some disparities in access to these medications. However, expanded coverage could also increase Medicaid drug spending and put pressure on overall state budgets. KFF analysis found that utilization and gross spending on GLP-1s nearly doubled each year from 2019 to 2022. In the longer term, however, reduced obesity rates among Medicaid enrollees could also result in reduced Medicaid spending on chronic diseases associated with obesity, such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and types of cancer.

This section provides information about:

- Managed care’s role in administering pharmacy benefits

- Pharmacy cost containment

- Coverage of obesity drugs

Findings

Managed Care’s Role in Administering Pharmacy Benefits

Most states that contract with MCOs include Medicaid pharmacy benefits in their MCO contracts, but eight states “carve out” prescription drug coverage from managed care. While the majority of states that contract with MCOs report that the outpatient prescription drug benefit is carved in to managed care (31 of 42 states that contract with MCOs), eight states (California, Missouri, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Tennessee, Wisconsin, and West Virginia) report that pharmacy benefits are carved out of MCO contracts as of July 1, 2024 (Figure 17). This count is unchanged from last year’s survey, though Utah noted considering future pharmacy delivery model changes such as carving out the pharmacy benefit from MCO contracts following a legislature-initiated study. There has been an increase from one state (Kentucky) to three states (Kentucky, Louisiana, and Mississippi) that now contract with a single PBM for the managed care population instead of implementing a traditional carve-out of pharmacy from managed care. Under this “hybrid” model, MCOs remain at risk for the pharmacy benefit but must contract with the state’s PBM to process pharmacy claims and pharmacy prior authorizations according to a single formulary and PDL.

Half of states that contract with MCOs report targeted carve-outs of one or more drugs or drug classes. As of July 1, 2024, 21 of 42 states that contract with MCOs reported carving out one or more drug classes from MCO capitation payments (Figure 18). These targeted drug carve-outs can include drugs covered under the pharmacy benefit or the medical benefit and may be used as a MCO risk mitigation strategy or for other reasons, including enrollee protection. Some of the most commonly reported drug carve outs include hemophilia products, spinal muscular atrophy agents, other cell and gene therapies and/or high-cost specialty drugs. Notably, three states noted carving out the recently approved gene therapies for sickle cell disease. Over half of people with sickle cell disease are covered by Medicaid and CHIP, and enrollees with the disease typically incur high medical and pharmacy costs. The new therapies could potentially cure individuals of the disease but come at a steep cost, making them particularly promising as well as challenging for state Medicaid programs. When asked to describe any significant changes to how drugs are administered for FY 2025 and beyond, three states (New Hampshire, Texas, and Washington) did note they will be reversing (or carving back in) a specific drug class carve out.

Cost Containment Initiatives

Nearly three-quarters of responding states reported at least one new or expanded initiative to contain prescription drug costs in FY 2024 or FY 2025. In this year’s survey, states were asked to describe any new or expanded pharmacy program cost containment strategies implemented in FY 2024 or planned for FY 2025, including initiatives to address PBM spread pricing and value-based arrangements. States were asked to exclude routine updates, such as to PDLs or state maximum allowable cost programs, as these utilization management strategies are employed by states regularly and are not typically considered major new or expanded policy initiatives.

The largest share of states noting new or expanded cost containment policies reported initiatives related to value-based arrangements (VBAs) with pharmaceutical manufacturers as a way to control pharmacy costs. Half of responding states reported working toward, implementing, or expanding VBA efforts in FY 2024 or FY 2025, up from one-third in FY 2023 or FY 2024. This includes states that are just beginning to lay the groundwork for VBAs in their state, which can include submitting a State Plan Amendment (SPA) and negotiations with manufacturers. A recent HMA survey of state Medicaid programs found that nine states had VBAs in place as of July 1, 2023 (up from seven as of July 1, 2022), with the most frequently targeted drugs for VBAs including hepatitis C treatment and drugs used to treat spinal muscular atrophy. In this year’s survey, five of the nine states with VBAs in place reported efforts to further expand VBAs. State interest in VBAs appears to be accelerating, though states can face a number of barriers to implementing VBAs including manufacturer willingness as well as the administrative burden and complexity of the agreements. Though not specifically asked about in this year’s survey, eight states noted interest or intent to join CMS’s Cell and Gene Therapy Access Model, where CMS will negotiate an outcome-based agreement for cell and gene therapies (starting with the gene therapy for sickle cell disease) on behalf of states and provide technical assistance.

While VBAs were the most commonly reported initiative, states also reported a variety of other cost containment policy changes related to rebate maximization, high-cost drugs, and PBM reform. Specific cost containment policy changes reported in FY 2024 and FY 2025 include:

- Significant PDL or rebate changes. At least nine states reported new or expanded PDL or rebate changes, including changes in states with uniform PDLs that apply to both FFS and managed care. Seven of those states (Alaska, Arkansas, Delaware, Kentucky, Massachusetts, South Dakota, and Washington) reported initiatives in FY 2024 to significantly update or expand their PDLs, including adding new drug classes. Two states, Delaware (in FY 2024) and Connecticut (in FY 2025), reported limiting coverage of over the counter (OTC) products; Delaware specially noted they will now only cover OTC products that are rebate eligible. Washington and Delaware reported implementing additional clinical criteria for both FFS and MCOs in FY 2024, and Connecticut noted requiring detailed clinical review for non-preferred medications in FY 2025. Lastly, South Carolina will transition to a uniform PDL for FFS and MCO drug coverage beginning in FY 2024.

- Pharmacy reimbursement changes. At least three states (Arkansas, Massachusetts, and Mississippi) mentioned incorporating products like diabetic supplies traditionally covered as a durable medical equipment (DME) benefit into their pharmacy billing policies. These changes can facilitate enrollee access, reduce administrative burdens and improve data tracking, and/or enable states to collect rebates on products.

- Additional changes that specifically target high-cost specialty drugs. At least six states reported new or expanded initiatives in FY 2024 to mitigate the cost impact of high-cost specialty drugs, including some biologic and/or physician administered drugs. Vermont reported an expansion of their policy requiring separate claims for certain high-cost physician administered drugs in order for the state to collect rebates on those drugs. Alaska and Maine also reported changes related to physician administered drug payment, and Vermont created a biosimilar drug management program. New York reported a number of initiatives targeting high-cost specialty drugs including expanding efforts to negotiate supplemental rebates for high-cost drugs and/or drugs approved under the accelerated approval pathway. New Jersey reported expanding their high-cost drug risk corridor for managed care contracts, and New Hampshire plans to implement one.

- PBM and MCO-related. At least eight states reported initiatives related to PBMs and/or MCO contracts. In FY 2024, Delaware expanded PBM reporting requirements, New Jersey added a requirement that MCOs have a pass-through model contract with their PBM, Tennessee implemented a risk-sharing model for PBM services, and South Carolina is expanding their MCO Drug Transparency Audit program. Two states, Hawaii (in FY 2025) and Rhode Island (not until FY 2026), reported new initiatives to prohibit PBM spread pricing. Mississippi, effective FY 2025, moved to contracting with a single PBM to process and manage pharmacy claims for all enrollees, including those enrolled in managed care. To increase transparency in MCOs, Oklahoma is adding an MCO pharmacist to provide direct oversight of MCOs in FY 2025.

- In addition to these, a small number of states also mentioned changes related to quantity limits or medication therapy management services.

Coverage of Obesity Drugs

Twelve state Medicaid programs reported covering GLP-1s when prescribed for the treatment of obesity under FFS as of July 1, 2024 (Figure 19). Among the 12 states that reported coverage of GLP-1s, 11 states cover all three GLP-1s currently approved for the treatment of obesity (Saxenda, Wegovy, or Zepbound); Mississippi covers Saxenda and Wegovy but not Zepbound, the newest GLP-1 approved for the treatment of obesity. Four additional states have coverage in place but only for one or more older generation products, resulting in a total of 16 states covering at least one medication for the treatment of obesity. The survey asked states about their coverage of “weight-loss medications when prescribed for obesity” and the statutory exception refers to agents used for “weight loss”; however, “obesity drugs” is used to refer to this group of medications throughout this report. Notably, Wegovy was recently also approved for the treatment of cardiovascular disease, and all states are required to cover Wegovy for that label indication. While the survey only asked about FFS coverage, MCO drug coverage must be consistent with the amount, duration, and scope of FFS coverage. MCOs, however, may apply differing utilization controls and medical necessity criteria unless the state’s MCO contract specifies otherwise. For example, a recent HMA survey found that a growing number of MCO states have adopted uniform PDLs requiring MCOs to cover the same drugs and most MCO states also require uniform clinical protocols for some or all drugs with clinical criteria.

All of the states that cover GLP-1s when prescribed for the treatment of obesity under FFS report that utilization control(s) apply. Eleven states noted prior authorization requirements, 11 states noted body mass index (BMI) requirements, nine states noted a comorbidity requirement, and four states noted step therapy requirements (Figure 20). States also mentioned other utilization controls including counseling or documented weight loss requirements.

Among those responding states that do not currently cover obesity drugs, half noted they were considering adding coverage, with a few states reporting plans to definitely add or expand coverage. North Carolina reported adding coverage starting August 1, 2024, and South Carolina reported plans to add coverage of additional obesity medications (current coverage is only for Orlistat, an older generation product) at the end of 2024. Also, Kansas reported broadening its existing coverage of Zepbound in FY 2024 after the state secured a supplemental rebate agreement with the manufacturer. Connecticut reported a legislative mandate to add coverage but has not yet implemented coverage.

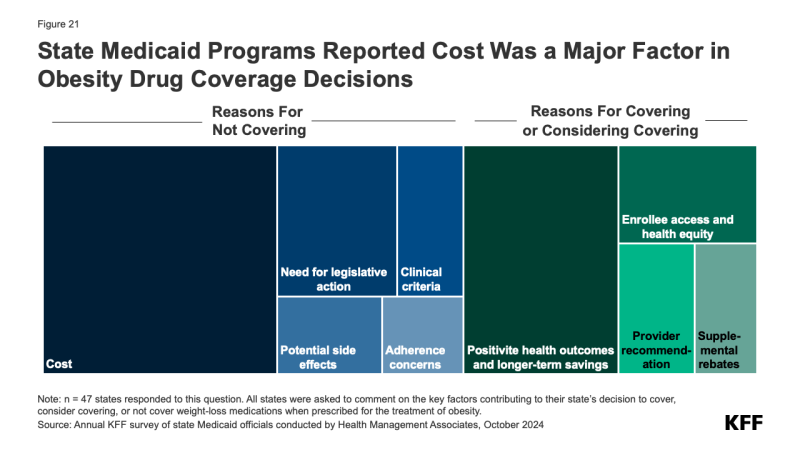

Almost two-thirds of responding states reported that cost was a key factor contributing to their obesity drug coverage decision (Figure 21). A few states mentioned they had conducted or are in the process of conducting studies to assess the cost implications of coverage in their state. A fifth of states also noted the need for legislative action such as changes to the state’s SPA or additional budget appropriations before they could implement coverage of these drugs. In addition, a few states mentioned concerns regarding adherence, developing clinical criteria, and potential side effects in their state’s decision not to cover obesity drugs at this time. Conversely, 4 in 10 states noted that positive health outcomes and longer-term savings on chronic diseases associated with obesity were key factors in their decision to cover or consider covering in the future. A few states also mentioned increasing enrollee access and health equity, recommendations from providers, and ability to negotiate supplemental rebate agreements were important factors.