COVID-19 Vaccinations by Race/Ethnicity: Differences and Limitations Across Measures

Since the rollout of the COVID-19 vaccines began, one issue that has been of focus is racial equity in COVID-19 vaccination rates. Ensuring equity in COVID-19 vaccinations is important given that COVID-19 has disproportionately affected people of color and may widen underlying disparities in health. Data are key for identifying disparities in COVID-19 vaccination rates and directing resources and efforts to address them. However, there are gaps in the federally reported COVID-19 vaccination data by race/ethnicity from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). To help fill these gaps in federal data, KFF and others have conducted ongoing analysis of state-reported vaccination data by race and ethnicity and regular COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor surveys with adults. These data have provided further insight into COVID-19 vaccination patterns by race/ethnicity, but also are subject to limitations. This brief provides an overview of these data sources, discusses their limitations, and explains why their findings may vary.

Vaccination Rates Across Data Sources

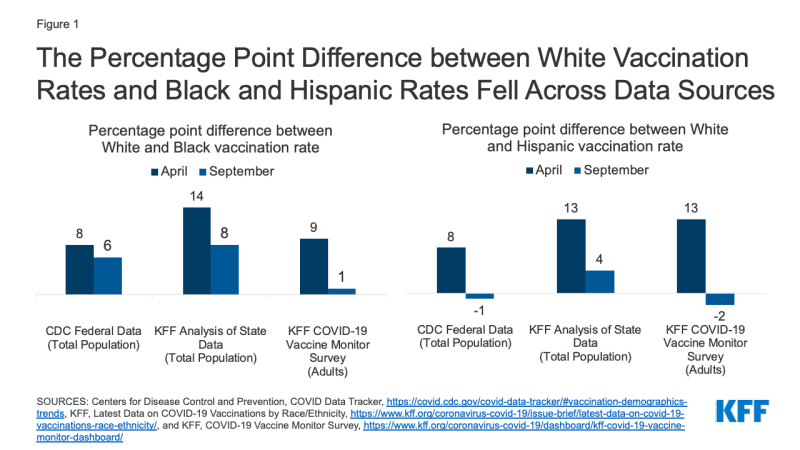

The federal and state administrative data and Vaccine Monitor surveys all show that Black and Hispanic people have been less likely to receive a COVID-19 vaccine compared to their White counterparts since the vaccination rollout began but that these disparities have narrowed over time. However, they vary in findings of the magnitude of this narrowing (Figure 1 and Table 1):

- The federal data from the CDC show that between late April and late September 2021, the percentage point gap between White and Black rates for the whole population fell by 2 percentage points (from 8 to 6 percentage points) while the gap between White and Hispanic rates fell by 9 percentage points (from 8 to -1 percentage points).

- The state-reported data find that the gap between White and Black rates for the total population fell by 6 percentage points over this period (from 14 to 8 percentage points), while the difference between White and Hispanic rates fell by 9 percentage points (from 13 to 4 percentage points).

- Vaccine Monitor survey data show the same trend with the difference between rates for White and Black adults falling by 8 percentage points (from 9 to 1 percentage points) and the gap between White and Hispanic adults narrowing by 15 percentage points (from 13 to -2 percentage points).

Figure 1: The Percentage Point Difference between White Vaccination Rates and Black and Hispanic Rates Fell Across Data Sources

| Table 1: Percent of People who Have Received at Least One COVID-19 Vaccine Dose by Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Date | White | Black | Hispanic | ||

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Total Population) |

April 30, 2021 | 27% | 19% | 19% | |

| Sept 20, 2021 | 41% | 35% | 42% | ||

| KFF Analysis of State Reported Data (Total Population) |

April 26, 2021 | 38% | 24% | 25% | |

| Sept 20, 2021 | 53% | 45% | 49% | ||

| KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor Survey (Adults) |

April 15-29, 2021 | 60% | 51% | 47% | |

| Sept 13-22, 2021 | 71% | 70% | 73% | ||

As of September 2021, the federal data from CDC show similar vaccination rates between Hispanic and White people, with lower rates persisting for Black people, and the highest rate for American Indian and Alaska Native and Asian people. Analysis of state data finds that Black and Hispanic people are less likely than White people to be vaccinated, but with a narrower gap for Hispanic people. The Vaccine Monitor survey data show that the gaps in rates for Black and Hispanic adults compared to White adults have closed, with no statistically significant differences in vaccination rates across these groups. A Pew Research Center survey conducted in August had similar findings.

This variation in findings reflects differences in what the data sources are measuring. Vaccination rates from the Vaccine Monitor surveys are based on adults, while the rates based on federal and state administrative data are for the total population (including children under 12 who are currently not eligible for vaccination). The inclusion of children in vaccination rates may lead to larger disparities due to racial differences in vaccination rates among adolescents eligible for the vaccines (ages 12-17) and because of the greater racial diversity of children relative to adults. Moreover, both the survey and administrative data are subject to different sources of measurement error, as discussed further below.

Federal COVID-19 Vaccination Data by Race/Ethnicity

The CDC reports the distribution of COVID-19 vaccinations and the percent of the total population who have received a COVID-19 vaccine by race/ethnicity at the national level. However, as of September 27, 2021, information on race/ethnicity was missing for over 40% of people who received at least one dose. Moreover, the data do not represent all states and jurisdictions, since not all states and territories are reporting demographic data on vaccine recipients to CDC. Given these data gaps, CDC indicates that the data are not generalizable to the entire population of individuals with COVID-19 vaccination. CDC does not report state-level data on COVID-19 vaccinations by race/ethnicity. Moreover, although CDC reports vaccinations by race/ethnicity and age separately, it does not publicly report data that allows for analysis of vaccinations by race/ethnicity and age. As such, the data cannot be used to examine whether there are larger racial disparities in vaccination rates among certain age groups, such as adolescents or younger adults.

State COVID-19 Vaccination Data by Race/Ethnicity

In the absence of CDC reporting state-level COVID-19 vaccination data by race/ethnicity, KFF has conducted ongoing analysis of data reported directly by states. As of September 20, 2021, 45 states, including Washington, D.C., were publicly reporting data on people who had received at least one COVID-19 vaccine by race/ethnicity and KFF was able to calculate total vaccination rates by race/ethnicity across 43 of these states. (Two states were excluded from the total due to differences in how they report their data). In general, these data are more complete than the data reported by CDC, with lower shares of vaccinations with unknown or missing race/ethnicity in most states. However, they also have gaps, limitations, and inconsistencies. As with the federal data, they do not include data from all states and jurisdictions and some states have relatively high shares of vaccinations with unknown race/ethnicity. For example, in Alabama, 37% of vaccinations had unknown race as of September 20, 2021. Further, states vary in their racial/ethnic classifications used to report the data, including how they classify people who identify as more than one race. Some state reported data does not include vaccinations administered through federal programs, including the Indian Health Service or the Long-Term Care Partnership Program.

COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor and Other Survey Data

Since December 2020, KFF has been conducting ongoing, nationally representative surveys of U.S. adults through the COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor. While these surveys have a broader purpose of measuring vaccine confidence, information needs, trusted messengers and messages, we have also used them to track the share of adults who report being vaccinated for COVID-19 over time. These surveys rely on probability-based sampling methods and researchers take extra steps to ensure the inclusion of populations that are often missed in surveys (including interviewing in English and Spanish and oversampling pre-paid cell phones that are commonly used by lower-income adults). Each survey also includes extra interviews with Black and Hispanic adults – using weighting to adjust survey respondents to match the distribution of adults in the U.S. — to be able to have greater statistical confidence when reporting on those groups (see the full methodology for more details).

Like all surveys, the Vaccine Monitor surveys are subject to a margin of sampling error around each estimate. For the September survey, the margin of sampling error was plus or minus 3 percentage points for the full sample, 4 percentage points for White adults, and plus or minus 7 percentage points for both Black and Hispanic adults. In addition, surveys may have other sources of error, including nonresponse error (certain types of people choosing not to participate in the survey or declining to answer the question about whether they have been vaccinated), measurement error (respondents not understanding the question that was asked), and social desirability bias (respondents giving answers they think the interviewer wants to hear). Despite these potential sources of error, the Vaccine Monitor surveys have tracked quite closely with CDC estimates of the share of adults overall vaccinated over time, and a recent Pew Research Center analysis of 98 different public polls conducted by 19 different polling organizations between December 2020 and June 2021 (including the Vaccine Monitor surveys) found that polling estimates of the adult vaccination rate have been within about 2.8 percentage points, on average, of the rate calculated by the CDC.

Conclusion

Data are pivotal for identifying and addressing disparities in health and health care. Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, gaps in data available by race/ethnicity have limited efforts to understand and address disparities. The availability and quality of data have improved over the course of the pandemic, but data gaps and limitations remain. To help fill gaps in federally reported data on COVID-19 vaccinations by race/ethnicity, KFF and others have conducted ongoing analysis of state-reported data on COVID-19 vaccinations and regular COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor surveys of adults, which have provided increased understanding of COVID-19 vaccination patterns by race/ethnicity. This, in turn, has helped to direct resources and efforts to address racial disparities in vaccination rates. While the federal, state, and survey data all show narrowing racial disparities in COVID-19 vaccination rates over time, they vary in the magnitude of this narrowing, with some surveys showing that gaps have closed, while the administrative data pointing to some remaining differences. This variation in findings reflects both differences and limitations across the datasets. Going forward, continued efforts to increase the availability of comprehensive, high-quality data will be key for identifying and addressing disparities for COVID-19 and in health and health care more broadly. Moreover, it will be important to continue to prioritize equity as vaccination efforts continue, people become eligible for booster shots, and eligibility expands to children, particularly given significant racial diversity of children.