Retiree Health Benefits At the Crossroads

Overview of Health Benefits for Pre-65 and Medicare-Eligible Retirees

Trends Among Employers Offering Retiree Health Benefits

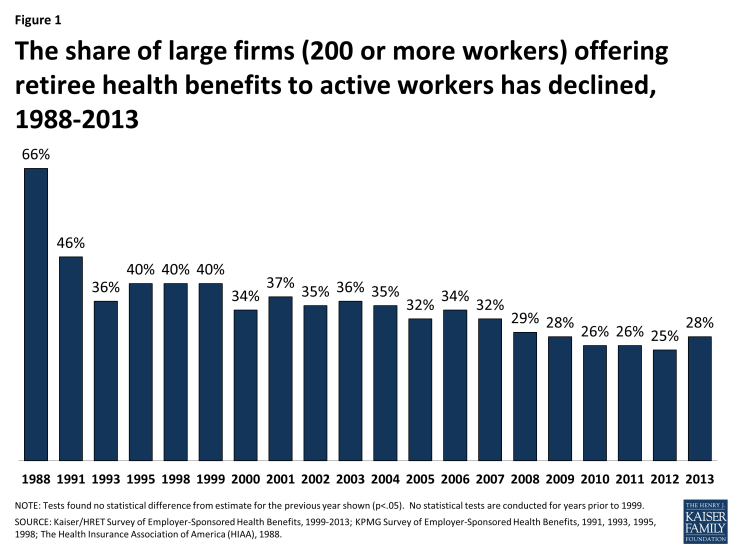

Over time, the share of large employers (with 200 or more employees) offering retiree health benefits has declined, and employers that continue to offer benefits have made changes to manage their costs, often by shifting costs directly or indirectly to their retirees. Since 1988, the percentage of large firms offering retiree health coverage has dropped by more than half from 66 percent in 1988 to 28 percent in 2013, according to the 2013 Kaiser/HRET Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Benefits (Figure 1). The biggest drop occurred between 1988 and 1991, after the Financial Accounting Standards Board required private sector employers to account for the costs of health benefits for current and future retirees. But ever since, there has been a more or less steady erosion in the percentage of firms offering retiree health coverage, dropping from roughly 40 percent of large employers in the mid-to late 1990s, to 28 percent of firms in 2013. Some firms elected to stop offering benefits (usually to future retirees first) while newer firms, and firms in the service and technology sectors, for example, never established the financial commitment to provide health benefits to their retirees. As a result of these changes, fewer than one in five workers today are employed by firms offering retiree health benefits.1

Figure 1: The share of large firms (200 or more workers) offering retiree health benefits to active workers has declined, 1988-2013

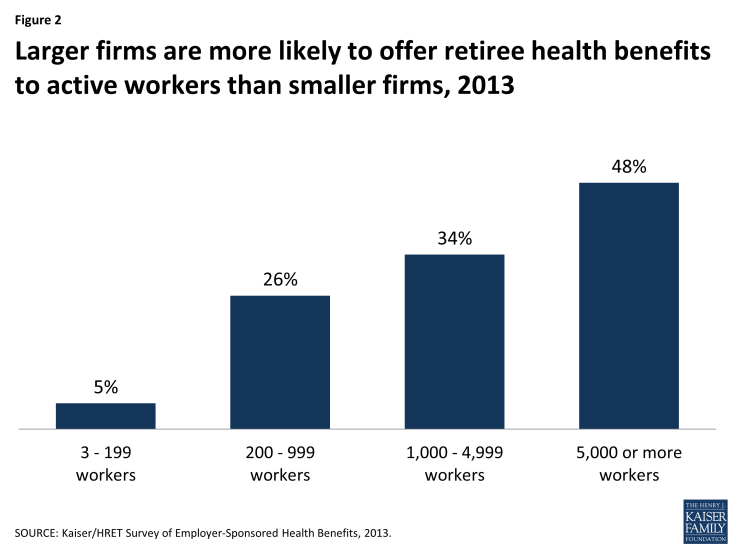

Large firms have always been much more likely than smaller firms to offer retiree health benefits to at least some of their former employees (Figure 2). Retiree health coverage is more typically offered to state and local government employees, and more often offered to employees in certain industries (such as finance) than to workers in the wholesale or retail industries, according to the KFF/HRET 2013 survey. Retiree health coverage is also more common among firms that pay higher wages, and more common among large unionized than non-unionized firms.

Figure 2: Larger firms are more likely to offer retiree health benefits to active workers than smaller firms, 2013

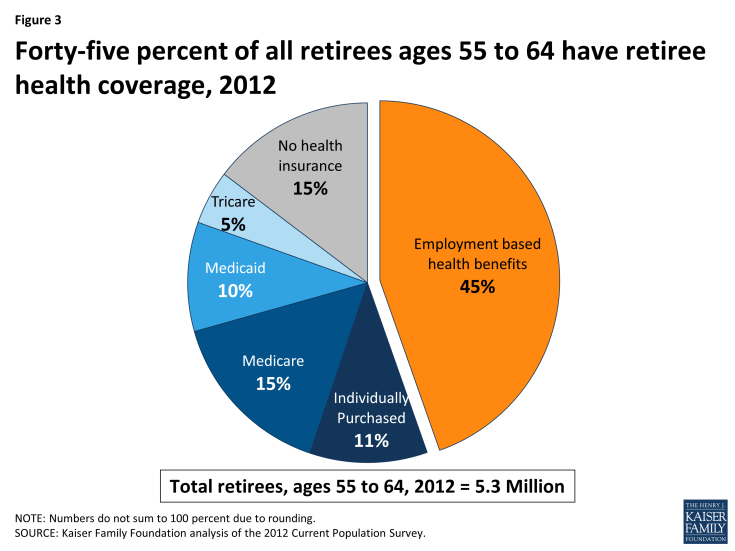

Coverage for Pre-65 Retirees

Employer-sponsored retiree health plans have historically played a vital role in contributing to retirement security for retirees who were too young to qualify for Medicare. In 2012, 45 percent of retirees ages 55 to 64 had health benefits from a former employer (Figure 3), reflecting a small decline from 2009, when 50 percent of early retirees had retiree health benefits.2 Prior to the availability of health marketplaces, insurance reforms, and subsidies provided by the Affordable Care Act (ACA), pre-65 retirees without access to employer-sponsored retiree health coverage or coverage from spouse had few good coverage options, as the availability of coverage for pre-65 retirees in the individual health insurance marketplace was unreliable, expensive, and subject to underwriting and potential denial of coverage. Though the cost of coverage for pre-65 retirees is substantially higher than for Medicare-eligible retirees, firms have been more likely to offer health benefits to pre-65 retirees. Among all large firms offering retiree health benefits, 90 percent of firms offered coverage to retirees under the age of 65, compared to 67 percent of firms offering coverage to Medicare-age retirees, according to the KFF/HRET 2013 employer survey.3

Large employers typically self-insure the benefits for pre-65 retirees and contract with health insurers to make available their provider network and administer the benefits and claims payments on a national basis. The employer may either combine the pre-65 retirees along with the active employees in the same risk pool, or break out the retirees in a separate risk pool. Most recently, as discussed further below, some employers that previously included active employees and retirees in the same plan have taken steps to create a separate legal plan for retirees only, as retiree-only plans are exempt from some of the more costly requirements of the ACA.

Employers offering pre-65 coverage typically offer the retirees the same health plan options that are available to active employees that, for large employers, would typically consist of a choice among several options, e.g., a PPO, an HMO, and (less frequently) a traditional indemnity plan. Such coverage is typically comprehensive and more generous than what Medicare currently provides, in that employer plans typically include a limit on out-of-pocket costs and provide a prescription drug benefit with no coverage gap. Often the employer will contract with a separate pharmaceutical benefit manager (PBM) to provide the prescription drug coverage (known as a “carve-out”), although sometimes the same insurer providing the medical benefits will also arrange to provide the prescription drug benefits (known as a “carve-in”).

A minority of large employers have changed their retiree health plans over the years in a move toward an account-based plan. With this approach, for example, an employer might credit employees between the ages of 40 and 55 with a fixed amount each year in a health reimbursement account (HRA), which the employees can then use to make their premium contributions to the health plan after they retire from the organization. Alternatively, an employer might offer employees high-deductible health plans as active workers and consider the eligible health savings account (HSA) as a vehicle that employees may use to accumulate funds that the employee can use toward retiree health expenses whether or not the employer actually sponsors a retiree health plan. HSA funds may not be used by pre-65 retirees to pay for retiree health plan premiums, but Medicare-eligible retirees can use HSA account balances to pay their Medicare premiums and premiums for retiree health plans (but not individually-purchased Medicare supplemental insurance policies, known as Medigap). The number of employers offering account-based health plans to active employers continues to grow, as does enrollment in such plans.

Premiums

The cost of providing retiree coverage to pre-65 retirees tends to be much higher than the cost of providing supplemental coverage to Medicare-eligible coverage because coverage for pre-Medicare retirees is primary rather than secondary. The average health benefit cost per retiree is roughly twice as much for pre-65 retirees as it is for Medicare-eligible retirees. According to data from Mercer’s National Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Benefits, the average annual health benefit cost per retiree was $11,961 for pre-Medicare retirees and $4,716 for Medicare-eligible retirees, among employers with 500 or more employees who provided cost information for both 2011 and 2012.4 Another survey, the 18th annual Towers Watson/National Business Group on Health Employer Survey on Purchasing Value in Health Care,5 reported the average cost for pre-65 retirees in 2013 (employer and retiree combined) was $9,064 for retiree-only coverage, and $4,583 for Medicare-eligible retirees. Typically, retirees are required to make a contribution toward the total premium, and in some instances, retirees pay 100 percent of the cost. According to the aforementioned Mercer survey, pre-65 retirees paid the full premium in 39 percent of the large employer plans (500 or more employees) offering retiree health benefits; employers paid the full amount in 12 percent of large employer plans. Among the remaining 49 percent of firms where the cost was shared, the average retiree contribution was 37 percent for pre-65 retirees. The results were similar among employers offering benefits to Medicare-eligible retirees.6

Coverage for Medicare-Eligible Retirees

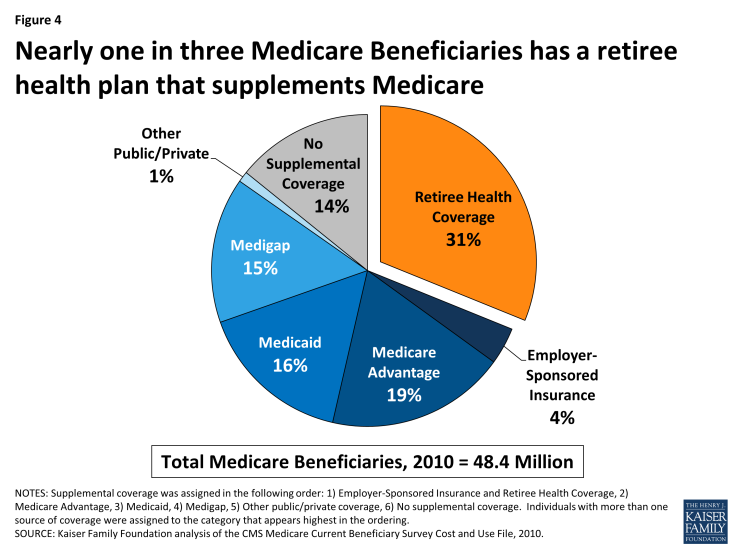

For retirees on Medicare, generally age 65 and older, employer-sponsored retiree health is the primary source of supplemental coverage (Figure 4). In 2010, nearly one-third (31%) of all Medicare beneficiaries had employment-based supplemental retiree health coverage. Another 4 percent were covered by an employer plan as an active worker, which means the employer plan was the primary payer.

Figure 4: Nearly one in three Medicare Beneficiaries has a retiree health plan that supplements Medicare

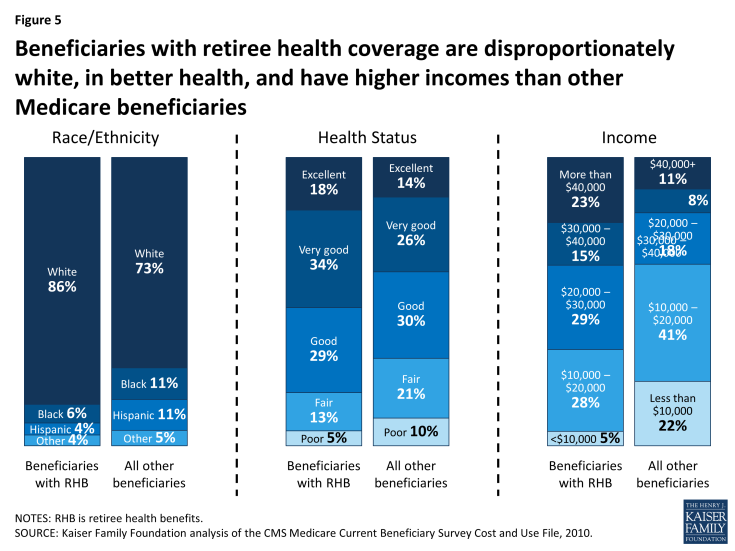

In general, Medicare beneficiaries with employer-sponsored retiree health benefits tend to have higher incomes than others on Medicare, are more likely to be white than black or Hispanic, and in relatively good health (Figure 5). The prevalence of retiree health coverage also varies geographically. Medicare beneficiaries living in the New England region are more likely than those in the South Atlantic and West North Central regions to have retiree coverage. The share of Medicare beneficiaries with retiree health benefits ranges from a high of 38 percent in the New England region (CT, MA, ME, NH, RI, VT) to a low of 28 percent in the South Atlantic region (DC, DE, FL, GA, MD, NC, SC, VA, WV) and the West North Central region (IA, KS, MN, MO, ND, NE, SD) (see Appendix Table 1 for the share of Medicare beneficiaries by region).

Figure 5: Beneficiaries with retiree health coverage are disproportionately white, in better health, and have higher incomes than other Medicare beneficiaries

Employer-provided retiree health coverage fills significant financial gaps for Medicare-eligible retirees. Medicare has relatively high cost-sharing requirements, and unlike typical employer plans, has no limit on out-of-pocket spending for services covered under Part A or Part B. Until 2006, Medicare did not cover outpatient prescription drugs, and even today, the Medicare drug benefit includes a coverage gap, or “doughnut hole” that will be phased down by 2020. Employer-sponsored retiree health plans help minimize the financial exposure of Medicare-eligible retirees by paying a portion of Medicare’s cost-sharing requirements, and in some instances, by paying for items that are not otherwise covered by Medicare (e.g., eyeglasses). By one calculation, a 65-year-old couple with Medicare retiring in 2013 without employer-sponsored retiree health coverage is estimated to need $220,000 to cover medical expenses throughout retirement, in addition to costs they may incur for over-the-counter medications, dental services, and long-term care.7

Employers use a variety of approaches to provide health benefits to Medicare-eligible retirees, as described below.

Self-Insured Employer Plans Supplement Medicare Benefits. The most common arrangement is where an employer sponsors a group plan that supplements Medicare, such as a preferred provider organization (PPO) or an indemnity plan, with a more generous package of medical and prescription drug benefits than traditional fee-for-service Medicare. For example, retiree health plans typically have a limit on out-of-pocket spending, unlike traditional Medicare, and will cover a larger share of retiree expenses for covered services that exceed the out-of-pocket limit. These plans are secondary to Medicare, which means that Medicare is the primary payer for each medical claim, and the employer plan will pay its portion of the claim after Medicare benefits are awarded. Typically the employer plan will coordinate with Medicare benefits using a “carve-out” approach, i.e., the employer plan calculates what it would pay toward the claim and then reduces its payment by the amount that Medicare pays.

Prescription Drug Coverage. With respect to prescription drugs, employer plans typically provide prescription drug coverage in conjunction with other medical benefits, and often these benefits are more generous than the standard Part D benefit (e.g., no coverage gap). Employers have the option to provide prescription drug benefits directly through an employer plan and receive a federal retiree drug subsidy (RDS) payment for offering qualified prescription drug coverage (that is, coverage that is at least equivalent to the Part D standard benefit). Alternatively, the employer may contract with a Medicare Part D prescription drug plan (PDP) on a group basis to provide prescription drug coverage to Medicare-eligible retirees, for which the employer pays a negotiated premium in addition to what the PDP receives from Medicare under Part D. Often the Part D plans receive a waiver from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to provide coverage exclusively to the employer group and the employer plan separately supplements the Part D plan benefits, a combination known more technically as Medicare Part D Employer Group Waiver Plans (EGWP) plus Wrap. Under these arrangements, employers contract with a Medicare Part D plan to provide benefits solely to the employer’s retirees, based on the standard benefit design, and the employer offers a secondary plan that supplements the first (waiver) plan to provide more generous drug coverage.8

Medicare Advantage Plans. Employers also have the option to contract with a Medicare Advantage plan (such as an HMO or PPO) on a group basis to provide supplemental benefits to its retirees, in conjunction with Medicare-covered benefits provided under that plan. With this approach, the employer plan negotiates with the managed care organization to define the supplemental benefits that are provided to their retirees. The managed care plan receives a capitated payment from Medicare for each retiree as well as the incremental additional employer plan premium for the negotiated supplemental benefits. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) established a federal waiver process to give employer plans greater flexibility to contract with Medicare Advantage plans by allowing such plans to limit enrollment to beneficiaries in the employer group and making it easier for an employer plan sponsor that wants to adopt a uniform strategy for covering retirees on a national basis.

Employers electing this option have benefitted from relatively high Medicare payments to group plans, which has helped to reduce the cost of providing extra benefits for their retirees, according to the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC).9,10 While employer-sponsored Medicare Advantage plans are subject to the same benchmarks as other Medicare Advantage plans, and are not eligible to receive bonus payments, they tend to receive higher federal payments than non-employer plans. This is because employer plans have an incentive to submit bids closer to the benchmark, while non-group plans have an incentive to bid below the benchmark.11 According to MedPAC, the average bid among employer group Medicare Advantage plans in 2014 was substantially higher than the average bid submitted by non-employer plans (95 percent and 86 percent of their benchmarks, respectively, weighted by projected enrollment), and as a result, average Medicare payments to employer-sponsored Medicare Advantage plans in 2014 are higher than for other Medicare Advantage plans.12

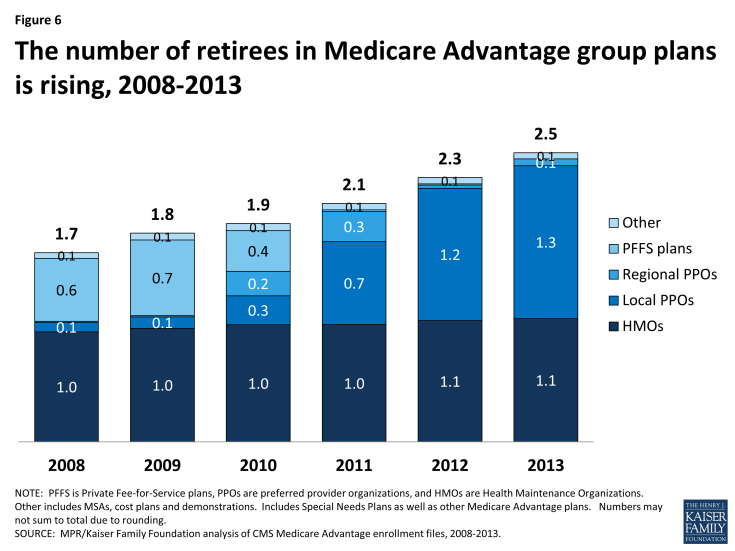

Once the employer contracts with the Medicare Advantage plan to provide benefits, the Medicare Advantage organization interacts directly with the enrolled retirees and with federal authorities, handles the administration and compliance responsibilities, and collects applicable Medicare payments. Today, 2.5 million Medicare beneficiaries are covered under group-based Medicare Advantage plans, up from 1.7 million in 2008 (Figure 6).13

The Administration in its FY2014 and FY2015 budgets has proposed to align payments for group plans with other Medicare Advantage plans for an estimated savings to Medicare of nearly $4 billion over 10 years .14,15 Similarly, in its 2014 report to Congress, MedPAC recommended a change in payment policy that would essentially reduce Medicare payments to employer group plans by basing them on the bids submitted by non-group plans, similar to the way it is done for Part D. It is unclear how these proposed changes in payment policy would affect future enrollment. Similarly, it is unclear what the effects would be of other recently-proposed rules from CMS that would make policy changes to the Medicare Advantage and Part D regulations without differentiating employer group plans.16

Health Reimbursement Accounts and Private Exchanges. A newer trend, discussed in greater detail below, is where an employer facilitates retiree access to Medicare Advantage, a Medicare Part D or Medigap plans offered through a private exchange on a non-group basis. Employers electing this approach typically make a defined financial contribution to a health reimbursement account (HRA) that is used by retirees to pay premiums in the plan selected by the retiree. Depending on the plan, the HRA may also be used to pay for out-of-pocket medical expenses. For these arrangements, employers may contract with a third party administrator or facilitator known as a “private exchange” to provide support and assistance to retirees in choosing from among a broad array of non-group plans of different types, plan designs, and costs.

Premiums

Typically, retirees are required to make a contribution toward the total premium, and in some instances, retirees pay 100 percent of the cost. According to Mercer’s National Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Benefits, retirees ages 65 and older paid the full premium in 40 percent of the large employer plans offering retiree health benefits. Conversely, large-employers paid the full amount in 14 percent of plans reported in the Mercer survey. Among the remaining 46 percent of plans where the cost was shared, the average retiree contribution was 38 percent for Medicare-eligible retirees. The results were similar among employers offering benefits to pre-Medicare retirees.17

Strategies Used by Employer to Constrain Retiree Health Costs

Surveys conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation and others have documented a trend among employers providing retiree health coverage of modifying their programs in an ongoing attempt to control retiree health costs.18 In addition to outright terminations of coverage, key changes reported by employers over the years include:

- Capping the employer’s contribution (or limiting the amount of the employer share of the total cost) for retiree health benefits;

- Tightening eligibility requirements, e.g., raising minimum age and service requirements;

- Raising retirees’ premiums and cost sharing, including changes that essentially eliminated first-dollar coverage for retirees;

- Eliminating coverage for future retirees, typically first for new hires, in some cases for current employees and, far less frequently for current retirees; and

- Optimizing savings from Medicare prescription drug coverage.

Yet despite such efforts, retiree health costs remain a significant concern for the dwindling number of employers that continue to offer this coverage for current workers and, failing that, for those covering a closed group of retirees with grandfathered coverage. For additional changes under consideration by employers, see the “Emerging Strategies for Employers Offering Retiree Health Coverage” section on page 12.