In Their Own Voices: Low-income Women and Their Health Providers in Three Communities Talk about Access to Care, Reproductive Health, and Immigration

Findings

- What do low-income women and their providers in San Francisco, Tucson, and Atlanta say about access to contraception?

- What do women and providers say about Medicaid coverage for reproductive care and other health services?

- What do women and providers in the different communities say about abortion access?

- How do mental health care challenges affect reproductive age women?

- What are the challenges in assisting survivors of domestic violence in the health care setting?

- How do the social determinants of health affect access to reproductive care?

- How have immigration enforcement practices affected access to reproductive health services?

What do low-income women and their providers in San Francisco, Tucson, and Atlanta say about access to contraception?

Most women who participated in the focus groups said they were able to get the contraception they want, but some expressed reservations about the quality of care and use of contraception in general.

Overall, most women stated that they have access to the contraception they seek. Providers reported that more women are expressing interest in long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), which include intrauterine devices (IUDs) and contraceptive implants. This reflects what has been shown in national data and contributes to fewer visits as well. Among some women, however, there is a degree of mistrust of providers when it comes to contraception. Providers also acknowledged the history of coercion and harm that was inflicted on many women of color with forced contraception makes some women fearful of using contraception.

When asked about where they obtain reproductive and sexual health care, women reported a range of sites. Several, particularly in Tucson and San Francisco, cited Planned Parenthood clinics and had positive experiences there. Women were particularly appreciative of the low cost or free contraceptives as well as the comprehensive counseling they received there.

SF English: “I’m happy [with my method]. I’m on the NuvaRing… I’m happy and I have all the options.”

SF Provider: “we have really started to train our staff to take their cues from our patients and let them have what they want… but… for somebody who is interested or unclear [we will] go through all the methods that we have available.”

Tucson English: “I think that was the best gynecology I’ve ever been to when I was young, when I was very young, was the Planned Parenthood. … They educated me on what they were giving me. They told me statistics, everything. They told me ‘you know you might gain weight on the pill we want you to start.’ They even gave you nutrition and everything.”

SF Provider: “I think there’s mistrust of birth control in general. And I think that’s where we get into, sort of, unconscious bias… But about a third of the young women who chose a LARC method, in that project, told us that their family and their friends disapproved of their choice. And I think some of that has to do with historical. I mean, you know, for women of color in this country, reproduction has always been controlled. And there’s always been an attempt to control reproduction.”

SF Provider: “I will say that we start talking about birth control during the prenatal period, and again during postpartum period. We’ve gotten feedback, that for some women, that feels very coercive. It’s like, it’s like almost, like there’s almost an overemphasis on birth control in some cases.”

Tucson English: “When I was offered the Essure [a non-surgical sterilization implant] I was handed the brochure. And I felt like this was when they were first really plugging it. I’m like, okay why is this only being offered to me and not other [methods]… And I knew there other options available.” [KFF clarification: Essure is no longer being used in the United States]

Out-of-pocket costs were a major barrier to care for low-income women, particularly those for who are uninsured and particularly for specialty services.

Uninsured women spoke extensively about out-of-pocket costs as a direct barrier to care. Many said they did not obtain preventive services, such as mammograms and diabetes screenings, because they did not have a source of coverage to pay for the services. When it comes to family planning services, many women said they were able to obtain free or lower-cost contraceptives at publicly-funded clinics, but some mentioned that they could not afford the sliding scale charges or any follow up visits. Some of the immigrant women in the groups said they went to their home country for health care, including contraceptives, because it was cheaper. Specialty services were unaffordable for many women, including those with insurance. Private insurance and Medicaid cover contraceptive services without cost sharing, but uninsured women are often charged on a sliding scale at safety net clinics.

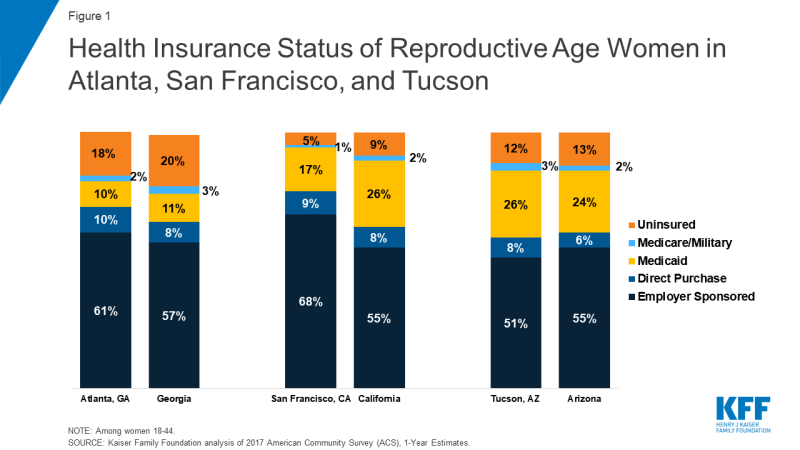

Reflecting different state choices regarding ACA Medicaid expansion, there were major differences in the profile of women’s coverage between the cities (Figure 1). In the San Francisco focus groups, only three out of twenty-one women were uninsured while in Atlanta 11 out of 16 were uninsured. Most women in the focus groups were working, but some were uninsured because they had jobs that don’t offer coverage, they did not qualify for Medicaid, and/or they were unable to afford the premiums.

Atlanta English: On being able to get contraception—“First of all they want to do an exam before they’ll give you anything, so the exam, they are like $250, $300.”

Tucson Spanish: “[If cost were not an issue] I would choose a surgery or IUD… but it is too expensive.”

Tucson English: “The copays were so high that I couldn’t even go to the doctor. I haven’t had my mammogram in about two years. And the last time it was a bad mammogram and my mom died of breast cancer.”

Tucson Provider: “Once [women] have to go into specialty care, then of course, those are the greatest barriers. That’s where we have difficulty because of our sliding scale. And especially in women, if we do have any issues with the Well Women Health Check there’s only screening, so they do not supply funding for treatment… And some women, we recommend that they have to return to Mexico, which is difficult.”

Tucson Provider: “I do think the only situation that has been a problem in our clientele is when we do offer colposcopy for abnormal paps, and the procedure is free, but what is not free is the lab if there’s a pathology or lab work, and so that has been a barrier. So women often choose not to have that service because they can’t afford it.”

Atlanta Spanish: “[Doctors] found an ovarian cyst in me because I didn’t have the chance to go in for check-ups every year. It took me two years to go back to my country [to get treatment] and when I went I had four cysts.”

Some women held misconceptions about contraception. Others also reported they did not receive thorough information about side effects, experienced language barriers, or relied on family and friends for information that was not always accurate.

Several women said they tried various contraceptive methods, but did not feel they had thorough conversations with their provider about the full range of methods they could choose from and side effects. For some, unexpected side effects resulted in discontinuing contraception or dissuaded them from trying a different method. Several women said it would have been helpful to have more information from their providers up front before starting a contraceptive. Among immigrant women, there was limited counseling because they could not always find providers who were fluent in Spanish. This leads to higher reliance on family and friends for health information, but some said that discussion about sex and contraception is not encouraged in some Latino cultures.

SF Spanish: “When I used the Mirena I thought the doctor would give me some sort of advice, but she never did… no one said I would experience those headaches, breast pain, bad mood. Your hormones go crazy and your period will eventually cease. I was feeling bad and didn’t know what was causing it. At some point they told me the device contained hormones.”

Tucson English: “I did the shot and I wasn’t told of any of the side effects. I had a period for three months. I became anemic. It was the most horrible experience and when I talked to the doctor he said, ‘you’re the point one percent. We can try it again and maybe it’ll be better,’ and I was like no-no, I’m not going to try it again.”

Tucson English: “With those [depo] shots they don’t tell you that you might not be able to get pregnant for five years after you stop taking the shot.” [KFF clarification: there is no medical evidence that this statement is true]

Atlanta Spanish: “I learned from my cousin’s experience. She started with the birth control very young, when she was like 15 years old. Now, she is 28 and she can’t have children because that kind of affected her.” [KFF clarification: there is no medical evidence that this statement is true]

Atlanta English: “When I was on the [depo] shot …I had all of these like fears about would I be able to have kids later, and not really knowing, it was never shared like what it was doing to me, what it was doing to my body and they were like oh you’ve been on this for seven years, we should probably take you off. So now I am not on any birth control just because I want to be able to have kids when I’m ready.”

Atlanta Spanish: “When I was growing up, my mother never told me about [contraception]. She didn’t want me to take [birth control] pills. She said, ‘You have to be aware of what you are doing. A pill can stop you [from getting pregnant], but you as a person can stop that better [with abstinence].’ I got pregnant the first time I had sex, the first time.”

Atlanta Spanish: “Sometimes I want to tell the physician what I feel, but there is no translator available, or maybe he doesn’t understand you or he doesn’t say what we are saying.”

Finances, attracting and maintaining a strong workforce, and stressful duties were underlying challenges for reproductive health care providers.

Safety-net providers, including those at federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), family planning and abortion clinics, health departments, shelters and other support agencies, discussed a number of challenges for remaining financially sustainable and maintaining high quality care. Many are operating within very tight budgets, which affects their ability to attract and recruit staff, remain competitive, and deliver services. In San Francisco, providers spoke about the difficulty of recruiting and keeping ancillary staff, such as technicians and health educators, because their organizations do not pay enough to keep up with the region’s high cost of living, In Atlanta, providers said that one challenge is their reliance on philanthropic grants, which are usually time limited. Funders may also change priorities, which has led some providers to discontinue programs, such as health education services, because they no longer fit into the funder’s portfolio. Planned Parenthood staff in particular expressed ongoing uncertainty due to the federal efforts to eliminate public funding to the organization.

Providers expressed real concern about their limited resources to address underlying issues with social determinants of health. Some expressed desire to fundamentally overhaul the systems they work in so that care is better integrated for women and so that they can follow up with patients to ensure they do not fall through the cracks of the health care system.

SF Provider: On ability to recruit staff, “How equitable our pay is compared to the market rate and being able to be sufficiently staffed so that we can serve our patients”

Atlanta Provider: “We want to create services that are conducive to [low income immigrant] populations, but at the same time [it’s] hard to have services after hours. … So it’s a balance of how can we cater to these populations without burning ourselves at the same time.”

Atlanta Provider: “So we’ve had a lot of layoffs. We’ve had new employees come on board that are being paid at a reduced, ridiculously reduced rate… And just, you know, taking those programs away so the community feels like they’re left out, that they’re not benefiting from the services, that their health or their issues aren’t as important as it once was when that’s really not the case.”

SF Provider: “In an ideal world, our clinic would have an area for child care. Our clinic would be able to provide transportation for those that may not qualify for transportation. We would have an on-site therapist. And maybe even an area where we can provide donations of diapers or baby items.”

What do women and providers say about Medicaid coverage for reproductive care and other health services?

Most low-income women relied on Medicaid coverage during pregnancy.

Known as Medi-Cal in California, AHCCS in Arizona, and simply Medicaid in Georgia, the program covers one in five low-income women nationally and pays for nearly half of births. All states are required to cover pregnant women up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL) through 60 days postpartum, and many states cover above this income level. Some women, most commonly in Georgia, reported losing coverage shortly after delivery. Because Georgia has not expanded its state Medicaid program, most women lose Medicaid coverage 60 days after giving birth and many become uninsured (Figure 2). Several women in Atlanta said that they did not go to postpartum visits because they were dropped from Medicaid after giving birth. The Medicaid income eligibility limit in Georgia falls from 225% of the federal poverty level (FPL) for pregnant women to 35% FPL for parents (annual income of about $7,466 for a family of three).

Loss of Medicaid coverage was also raised as a concern by some new mothers in San Francisco and Tucson, both in states that have expanded Medicaid under the ACA, and where most low-income mothers can still qualify for Medicaid beyond the 60-day postpartum period. Employer-sponsored insurance plans are required to cover maternity care, but unlike Medicaid, women may face substantial out-of-pocket charges, particularly if they are subject to a deductible.

Figure 2: Women’s Experiences Losing Medicaid Coverage After Childbirth is a Reflection of Lower Eligibility Levels for Parents Compared to Pregnant Women, Especially in Georgia and Other States that Have Not Expanded Medicaid

SF English: “With my daughter who’s four now, I had Medi-Cal, so I didn’t have to pay anything, which is great. And then I had my son a year and a half ago, and I didn’t have Medi-Cal, I just had benefits through my job. So I’m still paying for that.”

SF English: a woman with employer-based insurance, “…with my second daughter I was out of the hospital in less than 24 hours, and I didn’t have any medication. And I paid for three years, to be able to afford the delivery fee… I think it was like $3,000.“

Atlanta English: “Well short story is I had Medicaid and after I had my son, they just took it away… about six weeks in.”

Some low-income women raised the Catch 22 of earning “too much” to qualify for Medicaid and other public benefits.

While the women noted that they greatly value having Medicaid coverage, some raised the administrative challenges they experienced in obtaining coverage and staying enrolled in the program. They stated that income verification requirements can be burdensome and result in delays in coverage. Furthermore, some women said that earning just a little “too much money” can result in losing Medicaid coverage and other forms of public assistance. Some women discussed earning salaries that are just a few dollars above the income limits for food stamps and housing assistance, which are still very low.

SF English: “It took me like two months to be able to get on Medi-Cal in California. It was like a really, really hard process. They wanted like life insurance and car, like everything, proof of everything.”

Tucson English: “I had [insurance coverage] through my ex, lost it. Tried to apply for Medicaid but … I don’t qualify because I make too much for two people… I’ve got all this debt, I’ve got bills to pay, but they don’t look at that. All they look is just the bottom income.”

Atlanta Spanish: “What I don’t like when you are trying to get health insurance is that they consider only your overall salary; they don’t consider that you must pay rent, your bills, your kids. You end up with nothing. They don’t consider the debts. “

Tucson English: “[I don’t have insurance right now because] I bonused these past two months, so when it was time for me to reapply they said I didn’t qualify, so now I’m purposefully [trying] not to bonus. Because my medical is more important than a bonus.”

Most low-income women said that they do not have dental or vision coverage.

When asked about care that they are going without that they feel they need, many women across all three cities said that they do not have coverage for dental or vision services, with some women describing them as “luxuries.” Providers and women shared stories of dental and vision problems worsening because of lack of coverage for cleanings and checkups. Limited coverage for dental and vision care is a longstanding gap in many state Medicaid programs.

SF English: “For a while I didn’t have dental. And then my wisdom tooth grew … And I had to go get them removed, and it was $1,100 out of pocket…”

SF Advocate: “…With vision care, I see a lot of women who don’t have care for their vision and are almost blind. They need glasses but can’t afford them.”

Tucson Spanish: “I am waiting to go to Nogales [Mexico] to fix my teeth.”

Tucson Provider: “Generational poverty and never having had dental…I’ll have women that’s what they want, they want to get all their teeth pulled, and they’re 30 years old. It’s like wow. To get dentures because their teeth are just all rotten.”

What do women and providers in the different communities say about abortion access?

There are substantial differences in abortion access between San Francisco, Tucson, and Atlanta, and varying levels of knowledge about availability of services.

California has some of the strongest protections for reproductive health care access in the country, while Georgia and Arizona have enacted a number of restrictions on abortion availability (Table 1). More women in San Francisco openly discussed abortion access and experiences compared to the groups in Tucson and Atlanta. In San Francisco, most in the English group knew where to look for abortion services or how to find them online and most were aware that the state’s Medicaid program covers abortions. Providers in the Bay Area said that use of medication abortion has increased and that they were able to make referrals for abortions, but they could not always follow up to ensure that their patients actually received services.

|

Table 1: Abortion Laws in Arizona, California, and Georgia |

|||

|

|

Arizona |

California |

Georgia |

|

Gestational limit |

Viability |

Viability |

20 Weeks |

|

Waiting period after mandated counseling |

24 Hours |

|

24 Hours |

|

Abortion can only be performed by licensed physician |

✔ |

|

✔ |

|

Parental involvement in minors’ abortions |

Parental consent |

|

Parental notification |

|

Public funding of abortion |

Only in cases of life endangerment, rape, and incest |

Funds all or most medically necessary abortions |

Only in cases of life endangerment, rape, and incest |

|

Abortion coverage prohibited in ACA Marketplace plans |

✔ |

|

✔ |

|

SOURCES: Guttmacher Institute. State Laws and Policies, An Overview of Abortion Laws. As of July 1, 2019. |

|||

In contrast, women in the focus groups in Tucson and Atlanta tended to be less aware of where to obtain an abortion and less supportive of obtaining one or helping a friend who might need one. There are multiple clinics that provide abortion in the Atlanta area that serve women across Georgia as well as those living in nearby states. Since the focus groups were conducted, the state enacted a law that could ban the procedure as early as six weeks of pregnancy, which could severely curb abortion access for women throughout the Southeast region, if the law goes in to effect.

SF Provider: “Our demand for in-clinic abortion is declining…. I think it’s again, women have better access to birth control, and… as well as women, we notice, choose medication abortion more often than in-clinic abortion.”

Tucson Spanish: On whether paying for an abortion would be a barrier—“Yes, it would. We don’t have money to pay for a medical checkup that costs $40. Imagine paying more than that.”

SF Provider: Language as a barrier to abortion access—“We can discuss abortion but we cannot refer people to abortion, and they have to make those appointments on their own and make those phone calls on their own. And so when they don’t speak English, it’s already kind of a complicated system to navigate and that can be really challenging.

Atlanta Provider: “Children are not allowed within the clinic for safety reasons… And then having to find transportation or somebody to sit with the kids, and also if they want to be put to sleep or receive anesthesia for the actual surgery, finding somebody who would drive them. So it’s a lot of multilayered factors that prevent people or prolong their, when they seek abortions.”

How do mental health care challenges affect reproductive age women?

Unmet need for mental health services was one of the greatest challenges across all focus groups with low-income women, immigrant women, and their providers.

Several women in all of the focus groups stated that they contend with mental health challenges, which range from stressors of daily life to clinical diagnoses of depression and anxiety to more acute and severe conditions. Some women were receiving medications or therapy services, but many more were not receiving any services despite feeling that they needed mental health care. Many did not know where to obtain care, while others had poor experiences with services they had received, could not afford services, or were told they would have to wait months before getting an appointment. Many women spoke of the importance of caring for mental health to the same degree as physical health, but few felt they had the resources to do so. Stigma, lack of time and resources were also factors that discouraged some women from seeking care.

SF Spanish: “I was doing therapy when I had insurance but then I had to stop. I became my own therapist. Of course, it is not the same, there is nothing like having a therapist, but for now I do not have the money to pay more sessions.”

Tucson Spanish: “Well, two years ago I was diagnosed with postpartum depression and anxiety. Since I have been resident [in the US] for one and a half years, I do not qualify for [Medicaid]. Therefore, since I need drugs for anxiety and depression, I just cannot have them, because there is no health insurance and there is not enough money for insurance.”

Tucson Provider: “I think the majority of women will go without mental health. There’s always the stigma, and there’s always that sense that they have to be above all that, you know, they have to take care of their children and take care of everyone else before they take care of themselves.”

SF Advocate: “Women can get a visit with a therapist or receive mental healthcare, but the waitlist can be up to a year, 6 months minimum. And they are seen only when they are already hurting themselves or when they are in danger of hurting themselves.”

SF Advocate: “Unfortunately we have to deal with [mental health] issues in our community, because most women arrive with the huge trauma of having immigrated. Don’t forget that in the very process of immigration, you risk your life. Many of these women arrive here and keep it to themselves and try not to think about it anymore.”

Atlanta Provider: “We’re hearing that there’s a need [for mental health services] but when the need is offered sometimes it’s not being used… Sometimes it could just be they’re not ready to address the issues that are going on and so they have to be ready and willing to do it in order to seek those services… There’s a stigma to being thought of as crazy… especially for black women, you’re supposed to be strong. You’re supposed to be able to handle all things.”

Providers in all three cities say that, when it comes to mental health services, delivering high quality care and finding referrals for treatment is very challenging.

Family planning and other safety-net providers also said that they see many women who would benefit from mental health care, but they expressed frustration in trying to help their patients obtain services. Some providers noted lack of strong referral networks, limited capacity among a small pool of mental health clinicians that will accept low-income patients, and the restrictions imposed by insurance companies. They felt, as did the women in the focus groups, that there were real concerns about quality of care even after a woman is able to get an appointment.

SF Provider: “With mental health, the first challenge is, do they have those services covered by Medi-Cal? If not, then the challenge is, is it in their budget to be able to pay for the visit? If they are able to pay for the visit, do you have any challenges with transportation, anything that would prevent you from getting there or making it to your appointments?… And then also, not enough bilingual therapists in our area. It’s a language, language barrier too.”

Tucson Provider: “When they come in here, if we’ve identified the need for a mental health referral, it is actually just that, it is a referral… I’m not really sure what happens [after].”

SF Provider: “One of the other things that is a real big issue in terms of mental health care is the lack of concordant providers….Very unconscious racism can have a real impact of the sort of mental health care that patients receive and whether it’s actually appropriate or not.”

SF Provider: “I think, for instance, it’s very, very hard for a white provider to really understand what it is like to live as a person of color, particularly a black person… as much as we say we pay attention to sort of workforce development, there are even laws that make it more difficult …. For instance, you cannot even have an arrest on your record in order to become [a] licensed [mental health provider.”

What are the challenges in assisting survivors of domestic violence in the health care setting?

Many women discussed experiences with intimate partner violence, and providers spoke about the difficulties of connecting women to safe, high quality care and assistance.

A striking proportion of the women in the focus groups talked about their current and prior experiences of domestic violence and the emotional, financial, and health burden it can cause for themselves and their children. Reproductive coercion, such as stopping women from using contraception, is one form of domestic violence that women discussed. Similar to mental health, connecting women to reliable, expert care can be very difficult and takes more time than many providers felt equipped to offer. Providers discussed a need for establishing relationships with their patients who are experiencing domestic violence with continued follow-up to ensure they are getting the resources they need. Women, too, said that they were not always ready to disclose information about violence to their providers, particularly if they do not have a secure follow up plan in place.

Some women also feared the repercussions of reporting cases of domestic violence, including reprisals from their abuser. Furthermore, some, particularly immigrant women, said that interactions with the police made their situations worse, with police actually blaming women for the situation. Women also feared that charging a spouse or partner with violence would put them at risk of being separated from their children.

Tucson English: “I think the biggest thing was just realizing that [domestic violence is] so common. And you think it’s just you. And I mean everything everybody has said here, I have experienced it, I relate to it. It’s just crazy how common it is and how silent everybody is about it.”

Tucson English: “[The authorities] didn’t help. And actually I called them and they treated me like a criminal. I called the police on my husband and the police told me they were going to put me in jail and take our son away from me because he lied about what happened.”

Tucson Provider: “Domestic violence is still quite secretive, especially the women that I see for the well woman health check. They’re very dependent on their husbands. You know, most of them, they can’t get out of a relationship because they have no place to go.”

Tucson Provider: “I think sometimes as providers, we don’t push enough, you know, we let them, we ask them and if they say no, we don’t delve into it deeper. I think that for domestic violence and the dangers of women, that it really takes a lot of work in establishing a relationship where they feel comfortable enough to talk about it.”

SF Provider: “We don’t have a system in place for following patients who have screened positive for intimate partner violence or adolescents who are positive for not being safe at home. We turn it over to the authorities, but we don’t have a mechanism in place to follow them or to see that they’re getting the resources that they need.”

Atlanta Provider: “In this particular climate there is fear of reporting any kind of abuse for undocumented folks… because we’ve seen an increased collaboration between police departments and ICE.”

How do the social determinants of health affect access to reproductive care?

Household finances and the cost of housing are major sources of stress in low-income women’s lives and constrain their ability to obtain health care. Women also run up against logistical obstacles (e.g. time, transportation, child care) to getting routine health care.

The cost of living, gentrification, and lack of affordable transportation were identified as significant health care barriers by women and providers in all of the focus groups across San Francisco, Tucson, and Atlanta. Many women said they were living paycheck to paycheck and had a hard time saving money. While it is well known that the cost of living in the Bay Area is high, women in Atlanta and Tucson also talked about the effects of gentrification on their ability to stay in their communities as well as pay for other living costs. Women in all three cities said that there are more jobs available than in the past, but that heavy traffic and long commutes, particularly in Atlanta and the Bay Area, limited their ability to do things that are not needed immediately, such as obtaining preventive health care

On top of these systemic economic barriers, several women discussed logistical barriers as well, particularly limited time and long waits at doctors’ offices. Some said that they would be more likely to address their own health care needs if their jobs gave them paid time off to attend doctor’s visits or if they could accrue time off for medical visits. Women spoke about the importance of preventive care, but many said that they did not regularly obtain services, primarily because of the out-of-pocket costs, finding the time, and the logistics of going for more visits.

|

Affordable Housing |

Poverty |

Transportation |

Logistics |

|

SF Provider: “Housing is a health issue, and what we find is that as we’ve seen gentrification increase in all of our communities, we’ve seen women pushed out in all of our communities…. If they’re immigrant women… they are fearful of complaining to a landlord about substandard housing.” |

SF Provider: “I think we are really under-resourced in terms of support around the social determinants of health and [the] kind of support for those kind of basic needs that make people’s health better: food, housing, safety.”

|

Tucson Provider: “We have a terrible transportation system here in Tucson, which really prevents access to services” |

Tucson Provider: “We do have a barrier in that we’re only open in the times that many working people need to have access to our care.”

|

|

Atlanta Spanish: “As so many jobs are being created in Atlanta, the jobs are in companies and for people with higher education. Many of those people are coming here and building houses that are at least $400-500,000 dollars. We don’t have that kind of money to afford those houses.” |

Tucson Provider: “And especially for low income women and women of color, being able to actually access services goes beyond being issued that insurance card.” |

Tucson English: “like with the gestational diabetes when I was pregnant, at the clinic they wanted me to come in every week. But I didn’t have a car so it was really hard for me to get all the way up there on the bus every single week… I would go once a month, but they wanted me to go once a week” |

Tucson English: “Even when my son was real little and I did have insurance I found that I didn’t go to the doctor very much because I was a stay at home mom and I didn’t have access to babysitters.” |

How have immigration enforcement practices affected access to reproductive health services?

Many women and providers discussed the particular stresses associated with being a low-income immigrant in the U.S. and the impact of increased anti-immigrant sentiment under the Trump Administration. Since the 2016 election, providers have seen a drop in the number of immigrant women who seek health care services for themselves and their children.

Low-income immigrant women in all three cities report that the efforts by the Trump Administration to curb immigration have made them more isolated and hesitant to engage in everyday activities outside their homes, such as going to work and taking their children to school. In some communities, particularly Tucson, women and providers said that while they have been dealing with anti-immigrant attitudes for a long time, the fear of deportation did increase after the 2016 election. There were some references to particular state level laws targeting immigrants that have been in place for several years, including SB 1070 in Arizona and Senate Bill 350 in Georgia, which made driving without a driver’s license a felony and imposed heavy fines (Table 2).

|

Table 2: Selected Immigration Enforcement Restrictions |

|

Federal |

|

Under longstanding policy, the federal government can deny an individual entry into the U.S. or adjustment to legal permanent resident status (green card) if he or she is determined likely to become a “public charge.” Proposed in September 2018 and finalized in August 2019, the Trump Administration’s changes to public charge policies can now consider the use of certain previously excluded programs, including Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, the Medicare Part D Low-Income Subsidy Program, and several housing programs, in public charge determinations. |

|

Arizona |

|

SB 1070 and HB 2163, enacted April 2010 Requires state and local law enforcement to reasonably attempt to determine immigration status of a person involved in lawful stop, detention, or arrest, where reasonable suspicion exists that the person is an alien and is unlawfully present. (While the Supreme Court struck down portions of this law in Arizona v. United States, this particular provision was upheld). |

|

Georgia |

|

Senate Bill 350 amended Georgia Code §40-5-121 and: Makes driving without a state issued driver’s license a felony with a minimum fine of $500 and requires traffic courts to report offenders; when a person is convicted of driving without a license, the nationality of such individual should be ascertained by all reasonable efforts. Delegation of Immigration Authority 287(g) Immigration and Nationality Act: A federal program that allows state or local law enforcement entities to enter into a partnership with ICE in order to receive delegated authority for immigration enforcement within their jurisdictions. A number of Atlanta-area counties (Bartow, Cobb, Floyd, Gwinnett, Hall, Whitfield) participate. Georgia House Bill 87—Illegal Immigration Reform and Enforcement Act of 2011 Requires employers to verify eligibility of employees to work in the U.S., and allows police to verify certain suspects’ immigration status if they are unable to provide valid identification. |

Some women said that the more recent immigration restrictions have affected how frequently they or family members seek reproductive health care as well as care for ongoing chronic conditions. Providers, too, said they have seen these effects, particularly in the early days of the Trump Administration. Clinic administrators also discussed having to expend time and resources on reaching out to frightened patients to encourage them to seek care but also at the same time preparing for the possibility of ICE raids or other enforcement practices (such as requesting patient medical records).

Atlanta Spanish: “If I must, I will take my son out of Medicaid, even though they told me he was American and doesn’t affect me, but now that I am going to apply for citizenship it would be ideal to receive the least possible aids.”

SF Provider: “What I’m noticing is that patients might be more fearful at seeking [prenatal] services. Finally, when they do come in, they might be a little bit more advanced into their pregnancy. And when I ask them what challenges did you encounter in accessing care, they might say ‘Well I was concerned…if that was going to affect my ability to seek residency.’”

Atlanta Provider: “And even though [immigration] is not part of the health work that we do it really affects people’s access to these services. So trying to be very intentional on the risks that people face when they go to the doctor. Like these are not sanctuaries, these are not safe spaces anymore. So you need to be aware of that and you need to be able to inform people what are the risks involved in seeking services.”

Tucson Provider: “Well, actually it has worsened in the last couple of years, especially with the well-woman health check program. Women are not coming in. There is a lot of fear on their part. And I have noticed that it is taking a lot of us to go out and pretty much encourage women to come in and utilize the services that are available to them.”

Tucson Provider: “Here in Tucson particularly, there were people who really clamped down and stayed home. We had family members who wouldn’t come in to have their kids immunized, which was a big thing at school time.”

Immigrant women report they and family members are hesitating to sign up for public programs, particularly food stamps and WIC, as well as Medicaid.

Many immigrant women and providers who see them said they hesitated to enroll in public programs that they qualify for because they feared reprisals from immigration enforcement or negative impact on their citizenship applications. These focus groups were held shortly after the Trump Administration proposed new rules regarding “public charge,” which received widespread attention in the media and among immigrant advocates and communities. These rules were finalized in August 2019 and will go into effect in October 2019, and they will expand the range of public benefits that would be used in public charge determinations to include Medicaid for non-pregnant adults, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and several housing programs. While not all of the information that the women believed was necessarily accurate from a legal standpoint, the misinformation contributed to their fears of using benefits.

Tucson Spanish: “In my case I asked for the insurance for my kids, the ones that are born here, but later with the law of deportation, I stopped doing it.”

Atlanta Spanish: I don’t apply for food stamps, I don’t want them to think that I apply for so many things, because I’m already on DACA, I don’t want that to be a barrier.

SF Provider: “I think [public charge] is the main reason why [patients] are not accessing WIC. … Their status may not be resolved, but their kids are citizens. And if they’re sharing [with me] that they’re having financial difficulty and I say ‘did you know that there’s a program called Cal Fresh, where they can, depending on your income, maybe help with food?’ and they say ‘oh no-no-no, I plan to apply for my residency in the future and my lawyer has suggested I don’t seek any help.”

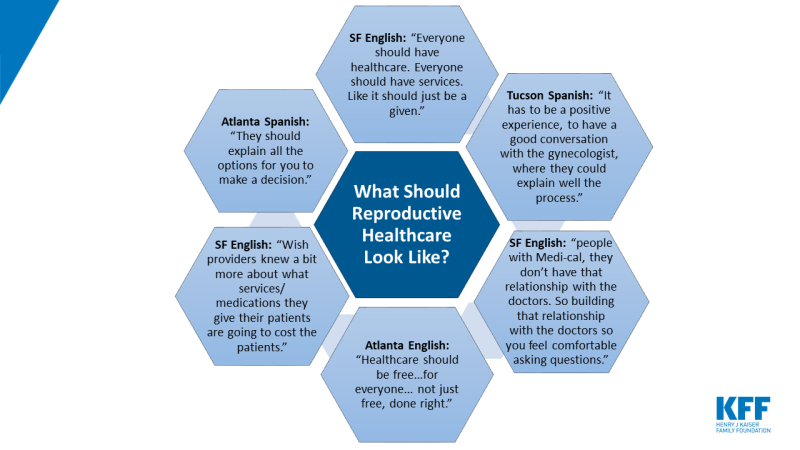

What do women say reproductive health care should look like?

Finally, when asked what reproductive health care in the U.S. should look like ideally, there was a lot of consensus across the three cities that lowering the cost and making it available to all is an important priority. Women also desired greater continuity of care and being able to develop a trusting and ongoing relationship with a provider. Given the sensitive nature of the care that reproductive age women tend to seek, this is a particular priority.