State Actions to Improve the Affordability of Health Insurance in the Individual Market

Introduction

The health insurance marketplaces established by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) provide coverage to about 11 million consumers. However, insurance premiums in these marketplaces have risen dramatically across most states in recent years. Even as premium increases moderated in 2019, the cost of coverage remained unaffordable for many. While consumers in the marketplace who qualify for premium tax credits are protected from these high costs, those with moderate incomes who are not eligible for subsidies bear the full costs of any premium increases. Older adults with income just above 400% of poverty (the cutoff for premium subsidies in the marketplace) face the greatest challenges affording marketplace coverage.1 Reflecting this affordability challenge, the number of unsubsidized enrollees in plans that comply with the ACA insurance market rules fell sharply from 6.8 million in 2016 to 3.9 million in 2018.2

A number of states have taken steps to provide consumers with more affordable coverage options, although their approaches differ.3 Some states are implementing strategies that lower premiums by building on, and increasing the stability of the individual market. These actions include implementing reinsurance programs; adopting state individual mandate requirements; providing enhanced state-funded subsidies to certain marketplace enrollees; and implementing a public plan option in the marketplace. Other states are following the lead of the Trump administration by expanding the availability of lower cost coverage sold outside the marketplaces that does not comply with ACA standards—an approach that could increase marketplace premiums further. This brief examines these different approaches and discusses the implications of state policy choices.

Background

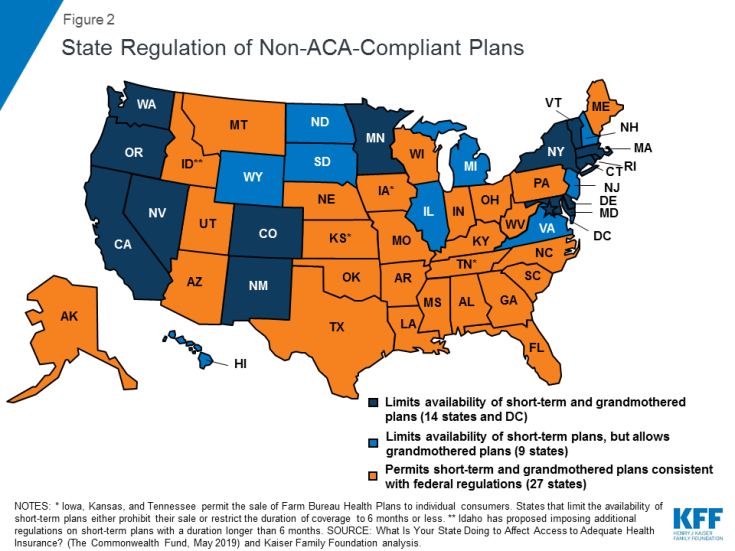

Since their rollout in 2014, the health insurance marketplaces have experienced significant volatility. Following premium increases in 2017 designed to stem early losses, the markets appeared to be stabilizing, suggesting premium increases for 2018 would have been modest. However, in response to policy decisions by the Trump administration to eliminate payments to insurers for required cost-sharing subsidies and reduce funding for outreach and enrollment assistance in the marketplaces, along with uncertainty over the future of the individual mandate, insurers responded by increasing average benchmark premiums by 33% for 2018 (Figure 1).4 It should be noted, because of a “silver loading” strategy used by most insurers to offset the effect of eliminating cost-sharing subsidy payments, subsidized consumers in the marketplaces were held harmless and in some cases were even better off as subsidies increased along with benchmark premiums.

Figure 1: Marketplace benchmark plan premiums have increased, but are stable for those with subsidies

Federal and state responses to premium increases in the marketplaces reflect the ongoing ideological divide over the ACA. Supporters of the ACA argue that best way to lower costs while protecting all consumers is to shore up the marketplaces by encouraging robust enrollment, particularly among young, healthy adults. With a balanced risk pool, multiple levers can then be used to lower premiums. In contrast, opponents of the ACA cite recent premium increases as evidence that the marketplaces are not working. They advocate loosening ACA requirements on alternative coverage sold outside the marketplaces to provide consumers with more lower cost options that generally provide fewer benefits and do not cover pre-existing conditions.5

Improving Affordability by Stabilizing the Marketplaces

Reinsurance Programs

A strategy that has proven popular among states across the ideological spectrum is reinsurance. Reinsurance programs address rising premiums by partially reimbursing insurers for certain high cost claims, which in turn, enables insurers to lower premiums for all ACA-compliant plans inside and outside the marketplace. Reinsurance programs take different approaches to defining reimbursable claims—some programs pay a portion of claims for consumers with certain medical conditions, while other programs reimburse a percentage of claims between specified dollar amounts. Evidence suggests these programs have been effective at reducing premiums in the individual market. Data from Alaska, Minnesota, and Oregon indicate that the implementation of the reinsurance programs led to lower premium increases than had been expected and prevented insurers from exiting the marketplaces.6 At the same time, while these programs lower premiums overall, they do not address the affordability challenges faced by consumers with moderate incomes, especially older adults, for whom premiums may still be unaffordable even after being lowered by as much as 10-15%.

One challenge states face with implementing a reinsurance program is the cost. States have used the ACA’s 1332 waiver authority to access federal pass-through funds to assist with financing reinsurance programs. To date, seven states (Alaska, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, New Jersey, Oregon, and Wisconsin) have approved reinsurance waivers, while four states (Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, and Rhode Island) have pending waiver applications (Table 1).7 These federal pass-through funds, however, do not fully finance the costs of the reinsurance programs. Some states rely on state general fund revenues, while others target specific funding streams. New Jersey is directing funds raised through its state individual mandate penalty toward the reinsurance program, and legislation to create a reinsurance program in Pennsylvania would be funded through savings generated by the state transitioning away from the federal marketplace to a fully state-run marketplace.8

| Table 1: Status of State 1332 Reinsurance Waivers | ||

| State | Date Approved or Submitted | Description |

| Approved | ||

| Alaska | July 7, 2017 | Allows federal pass-through funding to finance the state’s Alaska Reinsurance Program (ARP). The ARP fully or partially reimburses insurers for incurred claims for high-risk enrollees diagnosed with certain health conditions. |

| Maine | July 30, 2018 | Allows federal pass-through funding to finance reinstatement of the Maine Guaranteed Access Reinsurance Association (MGARA), the state’s reinsurance program that operated in 2012 and 2013. The MGARA reimburses insurers 90% of claims paid between $47,000 and $77,000 and 100% of claims in excess of $77,000 for high-risk enrollees diagnosed with certain health conditions or who are referred by the insurer’s underwriting judgment. |

| Maryland | August 22, 2018 | Allows federal pass-through funding to finance the Maryland Reinsurance Program. The plan reimburses insurers 80% of claims between $20,000 and $250,000. |

| Minnesota | September 22, 2017 | Allows federal pass-through funding to finance the Minnesota Premium Security Plan (MPSP), a reinsurance program that reimburses insurers 80% of claims between $50,000 and $250,000. |

| New Jersey | August 16, 2018 | Allows federal pass-through funding to finance the Health Insurance Premium Security Plan. The plan reimburses insurers 60% of claims between $40,000 and $215,000. |

| Oregon | October 18, 2017 | Allows federal pass-through funding to finance the Oregon Reinsurance Program (ORP). The ORP reimburses insurers 50% of claims between $95,000 and $1 million. |

| Wisconsin | July 29, 2018 | Allows federal pass-through funding to finance the Wisconsin Healthcare Stability Plan (WIHSP). The WIHSP reimburses insurers 50% of claims between $50,000 and $250,000. |

| Pending | ||

| Colorado | May 20, 2019 | Allow federal pass-through funding to finance a reinsurance program administered by the Colorado Department of Insurance. The reinsurance program will reimburse insurers 60% of claims paid between $30,000 and an estimated $400,000 cap. |

| Montana | June 19, 2019 | Allow federal pass-through funding to finance a reinsurance program administered by the Montana Reinsurance Association Board and the Commissioner of Securities and Insurance. The reinsurance program will reimburse insurers 60% of claims paid between $40,000 and an estimated $101,750 cap. |

| North Dakota | May 10, 2019 | Allow federal pass-through funding to finance the Reinsurance Association of North Dakota (RAND). RAND would reimburse insurers 75% of claims paid between $100,000 and $1,000,000. |

| Rhode Island | June 28, 2019 | Allow federal pass-through funding to finance a reinsurance program administered by HealthSourceRI. The reinsurance program will reimburse insurers 50% of claims paid between $40,000 and a cap of $97,000. |

State Individual Mandate Requirements

With the passage of the tax law at the end of 2017, Congress eliminated the penalty for not having health insurance beginning in 2019. The ACA individual mandate was considered an important tool for encouraging individuals, especially young, healthy adults, to purchase health insurance. Without the penalty, it is anticipated that some people, primarily healthier individuals, will choose not to purchase coverage, potentially driving up premiums for those who remain in the marketplaces. In November 2017, CBO estimated that the eliminating the penalty would lead to 4 million fewer people with health insurance in 2019 and 13 million fewer people with health insurance in 2027.9 Nearly 40% of the coverage losses would come from five million fewer people enrolling in non-group coverage in 2027.10

To stem this expected loss of coverage, three states (Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Vermont) and the District of Columbia have adopted state individual mandate requirements (Table 2). The individual mandate in Massachusetts predates the ACA mandate, while the mandate requirements in DC and New Jersey reinstate the ACA penalties, though each tie the maximum penalty to the lowest-cost bronze plans in their states.11 The individual mandate provisions in Vermont are being developed and are scheduled for implementation in 2020. Recently enacted legislation in California and Rhode Island establishes a state individual mandate.12,13 In some cases, states have earmarked funds expected to be raised from the individual mandate to fund reinsurance programs or other initiatives. As noted above, funds from the newly adopted individual mandate penalty in New Jersey are being used to finance the state’s reinsurance program.

| Table 2: States with Enacted Individual Mandate Requirements | ||

| State | Effective Year | Description |

| California | 2020 | Would reinstate penalty similar to the ACA. |

| District of Columbia | 2019 | Reinstates ACA penalty with a maximum penalty equivalent to the cost of the average yearly premium of a bronze-level plan in DC. |

| Massachusetts* | 2007 | Penalties:

|

| New Jersey | 2019 | Reinstates ACA penalty with a maximum penalty equivalent to the cost of the average yearly premium of a bronze-level plan in the state. |

| Rhode Island | 2020 | Would reinstate the ACA penalty with a maximum penalty equivalent to the cost of the average yearly premium of a bronze-level plan in the state. |

| Vermont | 2020 | Details of penalty are still to be determined |

State-funded Enhanced Subsidies

Another strategy some states have adopted to improve affordability is to provide state-funded subsidies that wrap around federal premium tax credits and cost sharing reductions. Currently, two states—Massachusetts and Vermont—offer such subsidies. Both states provide additional premium and cost sharing subsidies to people with income up to 300% of the federal poverty level. Neither state extends subsidies to those with income above 400% FPL.

More recently, a number of states have proposed enhancing premium subsidies, particularly for individuals with income above 400% FPL who are not eligible for federal premium tax credits. California will provide temporary state-funded premium subsidies to consumers with income up to 600% FPL and will further enhance subsidies for consumers with incomes from 200-400% FPL for coverage years 2020 and 2021.14 Additionally, legislation passed in Washington requires the state to develop a plan to implement and fund premium subsidies for individuals with incomes up to 500% FPL to limit what they pay in premiums to no more than 10% of household income.15

Similar to reinsurance programs, one of the barriers to implementing state-funded subsidies is the cost. Massachusetts and Vermont were able to leverage existing Medicaid 1115 waivers to secure federal Medicaid matching funds to help finance their subsidies; however, states proposing to extend subsidies to those with income above 400% FPL would not be able to access Medicaid funds in the same way. California will use money generated from imposing individual mandate penalties to partially finance these costs, along with general fund contributions. In Washington, the revenue source for the enhanced subsidies has not been specified.

Public Plan Option

Mirroring proposals at the federal level, a number of states have proposed public plan options. Broadly defined, these proposals include public plan options offered as qualified health plans (QHPs) in the state’s marketplace or a Medicaid or Basic Health Plan (BHP) buy-in plan primarily targeting moderate-income individuals in the marketplace. During the 2019 legislative session, a flurry of proposals were debated garnering a great deal of attention; however, only Washington has so far enacted a public plan option. Two other states, Colorado and New Mexico, enacted legislation to develop public option/Medicaid buy-in plans for review by the legislature in upcoming legislative sessions.

Under the Washington state proposal, the Washington Health Care Authority, the agency that administers the Medicaid program and the state employee health plan, will directly contract with one or more private insurers to offer qualified health plans (QHPs) in the state’s marketplace beginning in 2021. QHPs would be offered at the bronze, silver, and gold levels. To lower the premium of the public plan, payments to providers are limited to 160% of what Medicare would have paid in aggregate for the same services, with special payment rules for rural hospitals and primary care services. The state projects premiums for the public plan options will be about 10% lower than for other plans in the marketplace.16

While narrowly crafted both to gain legislative approval and also to avoid the necessity of applying for a 1332 waiver to offer the public plan as a QHP, the Washington approach nevertheless offers an opportunity to test the concept of using a public plan to spur competition in the marketplaces and offer a lower-cost option to consumers. As Washington proceeds with implementation of the public plan, other states and federal policymakers will be watching how it addresses a number of key issues, including contracting with insurers, setting provider reimbursement rates, and securing provider participation, whether the public option can coexist with private plans, and whether the public plan proves to be a more affordable and attractive option for consumers.

Regulating the Availability of Coverage Options Outside the ACA Marketplaces

Health coverage that does not meet ACA consumer protection requirements is available outside of the marketplaces in many states. This coverage can take several forms, including short-term limited duration insurance, transitional plans, also referred to as “grandmothered” plans, and Farm Bureau health plans. Because these plans can refuse to sell coverage to people with pre-existing conditions and are not required to cover the ten essential health benefits, they are cheaper than plans that must meet these and other ACA requirements. The Trump administration and a number of states view this coverage as a more affordable alternative for some consumers, especially those who do not qualify for subsidies or who qualify for only limited subsidies in the marketplaces, and seek to make them more available. In contrast, other states view these plans as a threat to the stability of the marketplaces and the affordability of coverage for people with health conditions, and restrict their availability.

Availability of Alternative Coverage

In 2018, the Trump administration issued new guidance expanding the availability of short-term plans. These plans, designed for consumers who experience short gaps in coverage, are not required to meet any of the ACA standards, including guaranteed issue and renewability and required benefits. Consequently, these plans exclude coverage for pre-existing conditions, do not cover many health essential health benefits, such as mental health services, prescription drugs, and maternity care, and may impose lifetime or annual limits on coverage.17 Obama-era rules limited these plans to no more than three months and prohibited plan renewal. Under the new rules, coverage under short-term plans can last up to 364 days and may be renewed at the discretion of the insurer for up to 36 months.

Because these plans can exclude consumers with pre-existing conditions and offer more limited benefits, it is estimated that premiums for these short-term plans could be as much as 54% lower than premiums for ACA-compliant plans.18 With such substantially lower premiums, short-term plans will offer an attractive option to healthy consumers, particularly those who are not eligible for premium subsidies in the marketplaces and face the full cost of ACA-compliant plans. Under new 1332 waiver guidance issued by the Trump administration in November 2018, states can use waiver authority to provide subsidies to consumers purchasing short-term plans through private exchanges, expanding availability of these plans to a broader group of healthy individuals. However, wider availability of short-term plans risks driving up premiums in plans sold in the marketplaces, which will continue to cover consumers with pre-existing conditions and greater health care needs.

The Trump administration also extended grandmothered plans for another year, though December 2020.19 Grandmothered plans are those that were issued after the ACA was signed into law in 2010 but before the insurance reforms went into effect in 2014. As such, they are not required to meet most of the insurance market reforms that took effect on January 1, 2014, including guaranteed issue, community rating, and coverage of essential health benefits. Grandmothered plans cannot be sold to new policyholders, but can remain in effect for people who bought them prior to 2014. The Obama administration initially extended availability of these plans, and those extensions have continued under the Trump administration. Similar to short-term plans, because these plans were medically underwritten when enrollees originally purchased them, they are cheaper compared to ACA-compliant plans, and consumers enrolled in these plans are generally healthier.

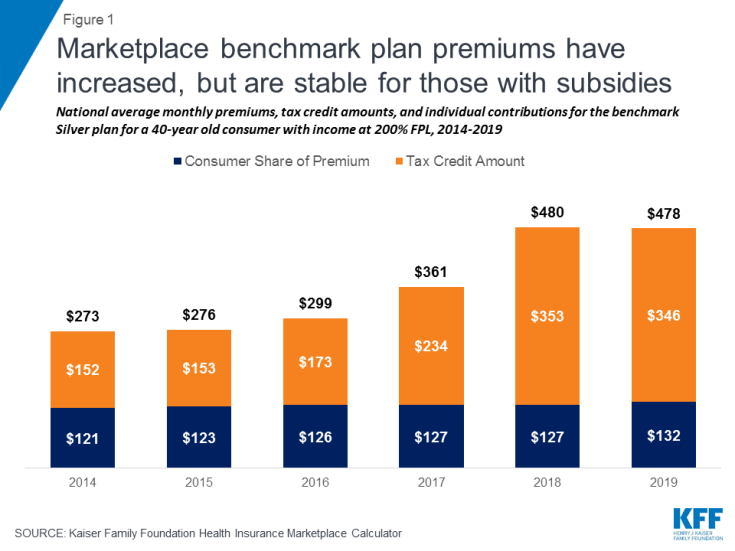

State Regulation of Short-term and Grandmothered Plans

States are primarily responsible for regulating short-term and grandmothered plans. They can choose to adopt the federal regulations making these plans and policies more broadly available or they can place greater restrictions on these plans than required by federal regulation (Figure 2). States are nearly evenly divided in their approach to regulating non-ACA-compliant plans. Just under half (24) limit the availability of short-term or grandmothered plans in some way, while 27 permit the sale of these plans in line with federal regulations (Figure 2).20 Among the states that restrict the availability of these plans, 14 states and DC limit short-term plans to no more than six months and also prohibit insurers from selling grandmothered plans. An additional nine states limit short-term plans, but permit insurers to continue selling grandmothered plans. Idaho appears to be taking a somewhat unique approach to regulating short-term plans. In a draft rule issued on July 3, 2019, the state proposed creating a category of renewable short-term plans that may be offered for longer than six months, referred to as enhanced short-term plans.21 While these plans can medically underwrite premiums and impose an annual limit on coverage, they must be offered on a guaranteed issue basis, can be renewed by the enrollee for up to 36 months, and must offer benefits consistent with the ACA’s essential health benefits.

Farm Bureau Plans

Three states, Iowa, Kansas, and Tennessee, allow Farm Bureaus to sell health coverage to individuals outside the marketplaces. These three states exempt Farm Bureau Health Plans from state insurance regulation, thus exempting them from the ACA’s health insurance consumer protections.22 Farm Bureau Health Plans have been available in Tennessee since 1993, while laws passed in Iowa in 2018 and in Kansas in 2019 have made them available in those states as well.23 As with short-term plans, exempting Farm Bureau Health Plans from ACA insurance requirements means that premiums for these plans can be significantly lower than for ACA-compliant plans, providing relief from high premiums to those who are healthy enough to meet the plans’ medical underwriting rules. However, that can also lead to adverse selection in the state-regulated individual insurance markets and drive up premiums for people with pre-existing medical conditions.24 Repeal of the ACA’s individual mandate penalty could lead to substantial increases in enrollment. Before the penalty was repealed, anyone enrolling in a Farm Bureau plan would have to pay the penalty because the plans did not meet the ACA’s minimum requirements.

Discussion

Actions taken by states in recent years to address rising premiums in the marketplaces sharply differ, reflecting divergent views on the success of the ACA and the role states should play in enforcing the ACA insurance market standards. These state policy choices have implications for the future stability of the marketplaces as well as on the affordability and availability of comprehensive coverage for all residents.

To ensure coverage is available for healthy and sick alike, a number of states have adopted strategies aimed at shoring up the marketplaces and enforcing ACA standards by limiting the availability of coverage outside the marketplaces. These states have sought to lower premiums using levers such as reinsurance programs or enhancing subsidies. One of the challenges states face with these approaches is the need for state financing. States are able to access federal funding through section 1332 waivers; however, an investment of state resources is necessary to have a meaningful effect on lowering premiums. Although reinsurance programs, in particular, have broad bipartisan appeal, the need for state financing has likely precluded more states from implementing these programs. Additionally, while other actions, such as establishing a state individual mandate or public plan option, may not require an investment of money, they require political consensus that may be hard to achieve in other states.

Importantly, state decisions over whether or how to regulate non-ACA-compliant plans will have significant implications for moderate-income consumers with pre-existing conditions. In states that allow non-ACA-compliant policies to proliferate as lower cost alternatives to qualified health plans for people who are currently healthy, adverse selection in the marketplaces will likely continue to drive up premiums. While consumers with lower incomes who are eligible for subsidies will be insulated from any premium increases, consumers with health conditions who do not qualify for subsidies may end up without any affordable coverage options.