Women and Health Care in the Early Years of the ACA: Key Findings from the 2013 Kaiser Women's Health Survey

Coverage, Access, and Affordability

Health insurance coverage is a critical factor in making health care accessible and affordable to women. Women with health coverage are more likely to obtain needed preventive, primary, and specialty care services, and have better access to new advances in women’s health. The primary goal of the ACA was to expand coverage to millions of uninsured across the country and to make reforms so that coverage is stable, affordable, and comprehensive. The law requires that most individuals have health insurance coverage in 2014 or pay a tax penalty. To facilitate access to coverage, the law includes a major expansion of Medicaid to many low-income individuals and establishes new Marketplaces in each state where most uninsured individuals who do not qualify for Medicaid can purchase a private insurance policy. While the law’s primary focus is on expanding coverage and reducing the number of uninsured, it also makes a number of other changes designed to make care more affordable and accessible.

Coverage

The ACA extends coverage to uninsured individuals through a combination of changes in private and public coverage. The ACA was designed to expand eligibility for Medicaid to the poorest individuals (less than 138% of the federal poverty level) and to make to make coverage more affordable and available to individuals with incomes between 100% and 400% of poverty by establishing state-based Marketplaces where individual can obtain coverage and receive assistance with premium costs through a graduated system of tax credit subsidies. However, because of a 2012 Supreme Court ruling, the Medicaid expansion is now optional for states; about half have decided not to expand their programs at this time. In the states that have not expanded Medicaid, this choice has had the consequence of limiting access to affordable coverage for the poorest uninsured residents and lowering the number of people who qualify for coverage under the program.

As the major part of the ACA’s coverage expansion begins, almost one in five women are uninsured.

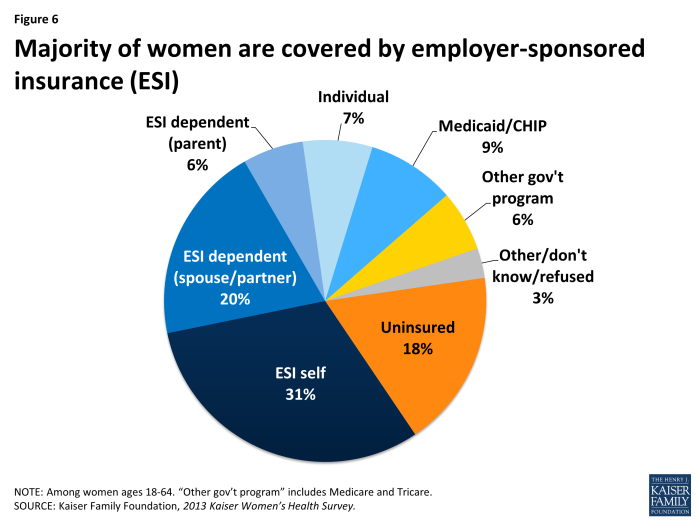

Most women (82%) have health coverage, but nearly one in five women (18%) between the ages of 18 and 64 are uninsured (Exhibit 3.1). Men, however, are uninsured at a higher rate (23%) than women. Employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) covers the majority of women (57%), with nearly half of that group covered as a dependent either through a spouse or parent. One in four women are covered as dependents (26%) and can be more vulnerable to losing their insurance should they become widowed or divorced, their spouse or parent loses a job, or if their spouse’s or parent’s employer drops family coverage. Just 7% of women are covered by private individually purchased insurance, with that proportion expected to change, as many turn to state-based marketplaces to obtain their coverage under the ACA. Currently, Medicaid, the nation’s coverage program for low-income individuals, covers about one in ten women (9%). Before the ACA was enacted, eligibility for Medicaid in most states was limited to women with dependent children, those who were pregnant and those with a disability. The ACA’s coverage expansion was designed to broaden Medicaid to many more low-income individuals and offer a new coverage pathway to poor adults without children who were largely ineligible before the law was passed. Although not all states are expanding Medicaid, the program’s enrollment is expected to grow significantly in the coming years.

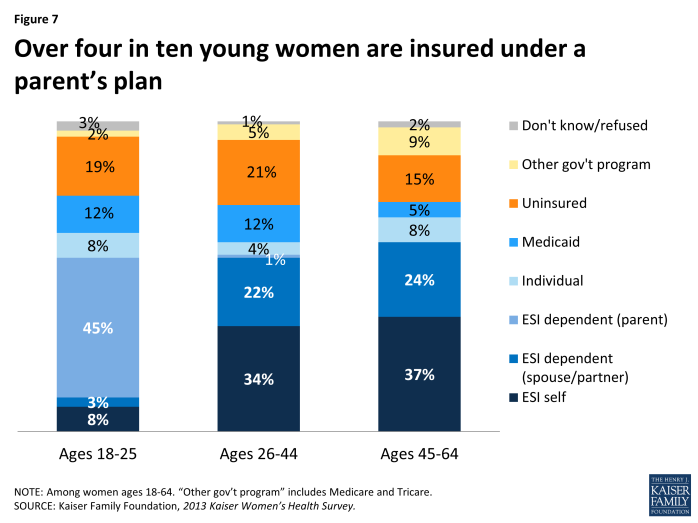

The ACA also included a major reform that allows adult children to stay on their parents’ health insurance policies up to the age of 26. This policy went into effect in 2010 and in 2013, many young adults were covered under their parents’ employer sponsored plans. While the overall rate of ESI coverage is similar between women of different age groups, 45% of women ages 18 to 25 are covered through a parent’s policy, accounting for the single largest segment of coverage in this age group (Exhibit 3.2). In prior years, this age group had the lowest coverage rates. Among women in older age groups, most women with ESI obtain coverage through their own job or through a spouse’s job. Medicaid also plays a prominent role for women under age 45, insuring 12% in that age group, a rate that is over twice the rate of middle aged women ages 45 to 64.

Lack of coverage is a problem facing a significant share of women of color.

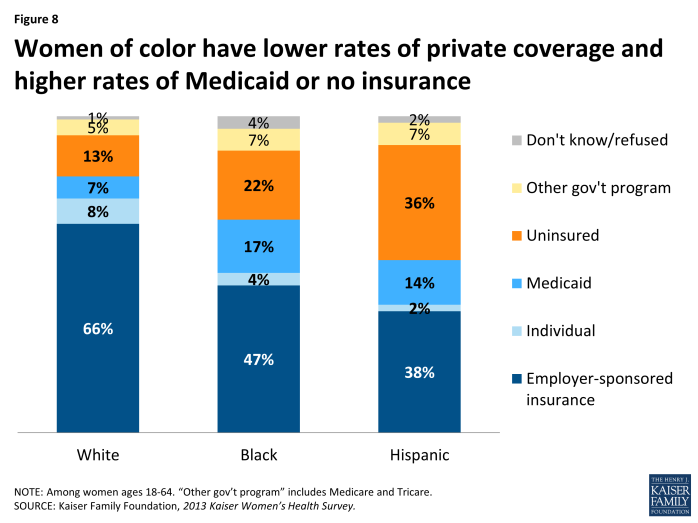

Minority women have higher rates of uninsurance and lower rates of employer-sponsored insurance compared to White women (Exhibit 3.3). While two-thirds of White women (66%) have insurance through an employer, either their own or as a dependent, this is the case for less than half of Black (47%) and Hispanic women (38%). These differences in part reflect the fact that minority women and their spouses are more likely to work in low-wage jobs that do not provide access to employer-sponsored insurance and have fewer financial resources to purchase coverage on their own. The rate of Medicaid coverage among Black (17%) and Hispanic women (14%) is double that of White women (7%), reflecting the lower average incomes and concentration of poverty among racial and ethnic minority women who may be more likely to qualify for the program. The highest uninsured rate is among Hispanic women (36%), followed by Black women (22%), compared to 13% of White women. However not all women have access to Medicaid or federal tax credit subsidies under the ACA. Most women who are recent immigrants (who on average have high rates of poverty) do not qualify for Medicaid for at least five years after entering the U.S. legally, as a matter of federal law. Undocumented individuals, however, do not have any avenue to coverage, as they are barred both from Medicaid eligibility and from purchasing a plan or receiving subsidies through the state-based Marketplaces.

Low-income women have much lower coverage rates, and even among those who are currently covered, some have been without insurance earlier in the year.

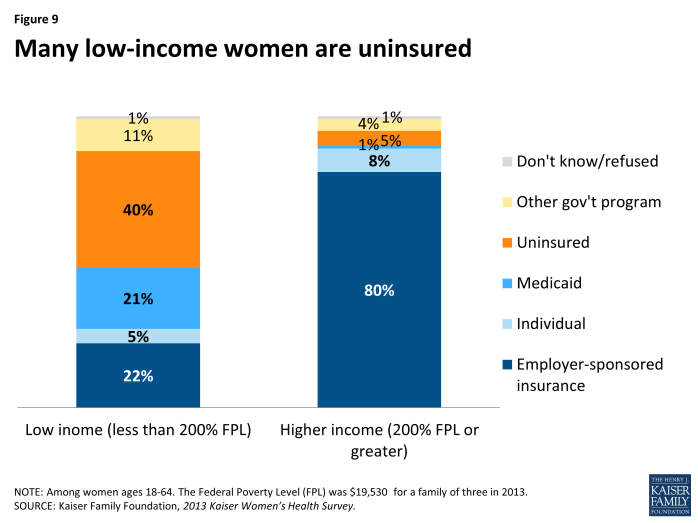

Four in ten low-income women (40%) are uninsured currently, compared to 5% among higher-income women (Exhibit 3.4). Not surprisingly, low-income women also have much higher rates of Medicaid coverage (21%) than their higher income counterparts (1%) due to Medicaid eligibility rules. They also have much lower rates of employer-sponsored insurance (22% vs. 80% respectively) than higher-income women largely due to the fact that they are more likely to work part-time or part-year, work in a low wage job that lacks health benefits, or live in a household without an attachment to the workplace.

Even among women who have insurance, coverage is not always stable. Women can have spells of being uninsured as a result of job loss or change, premium prices becoming unaffordable, or in the case of dependent coverage, a spouse’s job loss, or divorce or widowhood. While 82% of women report they had insurance at the time of the survey, a small share of that group report that there was a period in the prior when they were without insurance, which means that 77% were insured for the full year. Spells without insurance are more common among low-income women who have lower coverage rates to begin with. Only 53% of low-income women had coverage for a full year, compared to 90% of higher income women.

Access Challenges

While coverage plays a large role in accessing health care services, there are numerous factors that affect whether or not a woman actually obtains health care. These include health care costs, provider availability and capacity, as well as practical logistical issues such as transportation and finding time to make it to medical appointments. Some of these factors can be ameliorated by reforms in the ACA, such as the caps on out-of-pocket costs and the coverage expansions, but others are systemic such as workplace benefits and flexibility, child care, transportation, and the availability of health care in communities where low-income women reside.

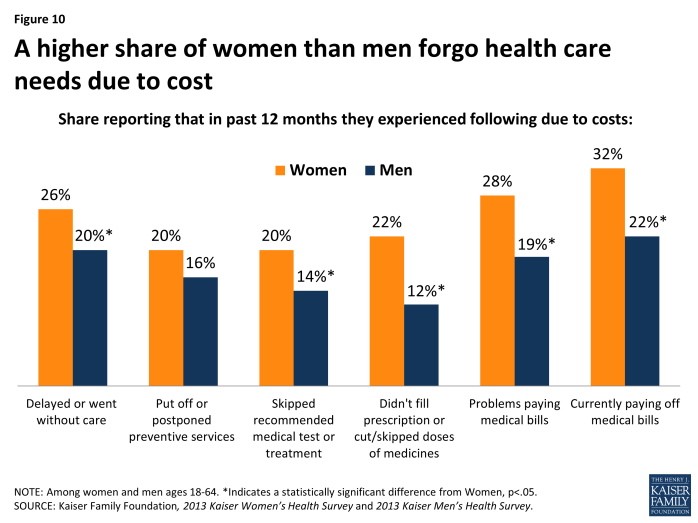

Out-of-pocket health costs are barriers to care for women and men, but are more common among women.

A higher share of women forgo health care needs due to cost compared to men. Insurance premiums, co-payments, deductibles, and services that are not covered by insurance can be expensive, potentially limiting access to care or jeopardizing a woman’s and her family’s financial health. While women and men both feel the impact of health costs, they are burdensome for a higher share of women, who on average earn lower wages, have fewer financial assets, accumulate less wealth, and have higher rates of poverty. This is compounded by women’s greater health care needs, including reproductive health care services, and higher expenses throughout their lifespans.

A sizable share of women report that health care costs impede their access to services, force them to make tradeoffs, or result in unpaid medical bills (Exhibit 3.5). Across the board, these problems are more common among women than men. One in four (26%) women and one in five men (20%) have had to delay or forego care in the past year due to cost. Because of costs, approximately one in five women have also postponed preventive care (20%), skipped a recommended test or treatment (20%), or made medication tradeoffs such as not filling a prescription or cutting dosages (22%). About three in ten women report that they have had problems paying medical bills (28%) in the prior year or are currently paying off medical bills (32%), compared to about one in five men who report problems paying bills (19%) or who are currently paying them off (22%).

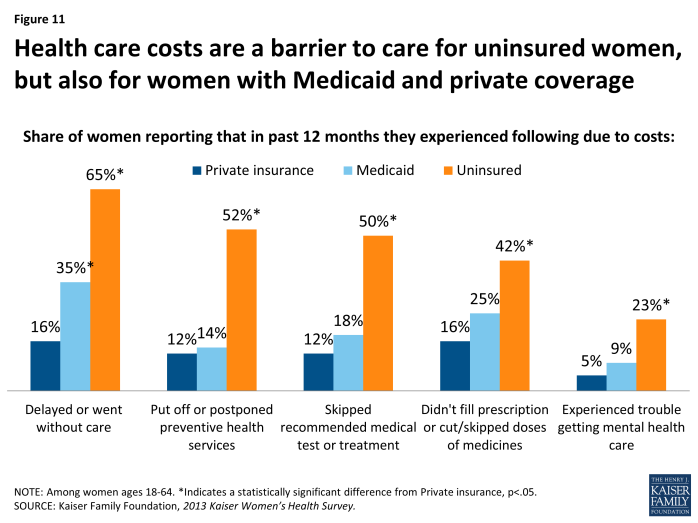

Costs are particularly burdensome for uninsured and low-income women.

For uninsured women, health costs can be a considerable barrier to care (Exhibit 3.6). Compared to women with private or public coverage, higher shares of uninsured women report that cost-related barriers to care. Almost two-thirds (65%) of uninsured women went without or delayed care because of the costs. Half postponed preventive services (52%) and half skipped a recommended medical test or treatment (50%). Four in ten uninsured women either didn’t fill a prescription or skipped or cut pills as a result of costs (42%) and about a quarter experienced problems obtaining mental health care (23%). However, it is important to recognize that even some women with coverage also experience affordability challenges that lower their access to health care. Sixteen percent of women with private insurance delayed or went without care because they could not afford it and many experienced other cost barriers as well. Although in some states Medicaid charges very nominal cost sharing amounts, this can still be an obstacle since women enrolled in the program have very low incomes by definition. One-third (35%) of women with Medicaid report postponing or going without care due to cost and many encountered other barriers too. One-quarter (25%) report that they made tradeoffs related to prescription drugs, which could be attributed to state policies that permit cost sharing or place caps on the number of prescriptions covered by their state Medicaid program.

| Table 3: Cost barriers to health care for women, by race/ethnicity and poverty level | ||||||

| All Women | Race/Ethnicity | Poverty Level | ||||

| Share of women reporting they: | White | Black | Hispanic | Less than 200% FPL | 200% FPL or greater | |

| Put off or postponed preventive health services due to cost | 20% | 18% | 23% | 23% | 35%* | 13% |

| Skipped a recommended medical test or treatment due to cost | 20% | 19% | 25% | 21% | 34%* | 14% |

| NOTE: Among women ages 18-64 reporting actions within past 12 months. *Indicates a statistically significant difference from White, 200% FPL or greater, p<.05.SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2013 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey. | ||||||

Not surprisingly, low-income women report cost-related barriers at significantly higher rates than their higher income counterparts. One-third of low-income women report that cost was a reason they postponed preventive services (35%) or skipped medical tests and treatments (34%), a rate that was over twice as high among women with higher incomes (Table 3).

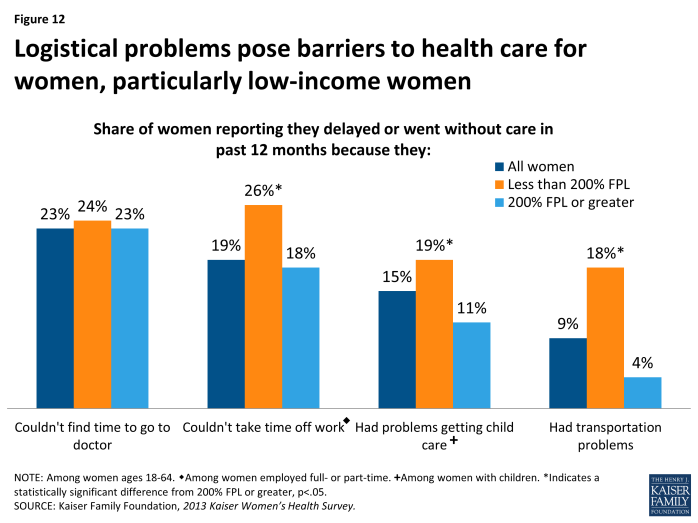

In addition to costs, women face logistical barriers to health care related to their roles as mothers and in the work place.

Costs and affordability are not the only barriers to health care for women. Lack of time and flexibility with work can pose a challenge in getting care for a sizable fraction of women. One in four women report that they did not obtain care they needed because they didn’t have time (23%) and one in five delayed or went without care because could not take time off work (19%). These barriers affect women of all socio-economic statuses to different extents (Exhibit 3.7). However, childcare and transportation problems are much more frequently reported among low-income women. Among women with children, one in ten (11%) with higher incomes report they delayed or couldn’t obtain needed care because they had problems getting child care, but the rate is almost double among low-income women (19%). For many women, getting to a doctor can be a challenge, but nearly one in five low-income women cited transportation problems as a reason for going without care (18%).

Impact of Medical Bills

Many women and their family members face problems paying medical bills for a variety of reasons. While this problem is greater for women who are uninsured, women with Medicaid and with private insurance also have difficulties covering their out-of pocket medical costs. Medical bills can easily pile up given high cost sharing, charges associated with out of network use, coverage limits or exclusions, or high deductibles for women with insurance. Uninsured women are often charged “full price,” a higher amount than the negotiated rate insurance plans pay for medical services, and do not have insurance to pay any of the costs of their care. Some women incur significant out-of-pocket medical expenses because of an unexpected health event such as a pregnancy, illness, or injury. These events may also limit a woman’s ability to continue working and result in lost income, further limiting her ability to pay medical bills. Medical debt can have serious financial consequences. Prior research has found that it is the leading reason for personal bankruptcy, and can cause women to exhaust their savings, make tradeoffs with other needed expenses, or compromise their credit standing.1 As more women gain coverage under the ACA, this should help alleviate the impact of medical bills but for some women, there could still be considerable costs associated with care, even among those gaining coverage.

Problems paying medical bills are reported by a sizable minority of women.

Approximately three in ten women have had problems paying medical bills in the past year (28%) compared to 19% of men. Nearly a third of women say they currently have medical bills that are unpaid or are in the process of paying them off (32%), also at a rate that is higher than for men (22%). Not surprisingly, uninsured women report problems paying medical bills in the prior year (52%) and having current outstanding bills (52%) at twice the rate of women with private insurance (21% and 26% respectively) (Table 4). This is however still a problem for a significant fraction of women with insurance. About one-third of women covered by Medicaid, who have very low incomes to use to pay off medical debt, also report having problems (37%) with medical bills or are currently paying them off (36%). These problems are also more common among younger women, who also tend to have lower earnings.

| Table 4: Rates of unpaid medical bills, by age group, insurance status, and poverty level | ||||||||

| All Women | Age Group | Insurance Status | Poverty Level | |||||

| Share of women reporting: | Ages 18-44 | Ages 45-64 | Private insurance | Medicaid | Uninsured | Less than 200% FPL | 200% FPL or greater | |

| They or family member had trouble paying medical bills in past 12 months | 28% | 31% | 26% | 21% | 37%* | 52%* | 44%* | 21% |

| They currently have unpaid medical bills or bills currently being paid off | 32% | 35% | 28%* | 26% | 36% | 52%* | 46%* | 25% |

| NOTE: Among women ages 18-64. *Indicates a statistically significant difference from Ages 18-44, Private insurance, 200% FPL or greater, p<.05.SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2013 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey. | ||||||||

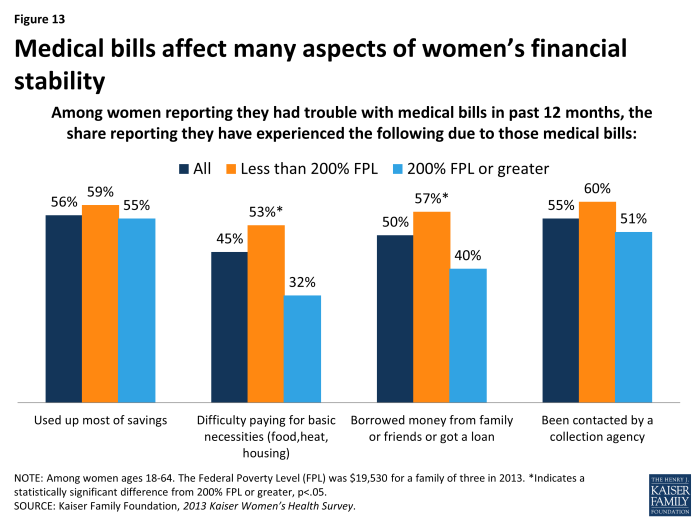

Medical bills have serious consequences for women’s finances and can force women to make difficult tradeoffs.

Medical bills have tangible consequences for other areas of women’s financial security. Among women reporting they had problems paying medical bills in the prior year, more than half report that they used up most of their savings (56%) or were contacted by a collection agency (55%) as a result of those bills. Many women also say they have had to borrow money from family or friends (50%), and or faced difficulties in paying for basic necessities such as food and electricity (45%) because of their medical bills. Not surprisingly, higher shares of low-income women face these difficult tradeoffs attributable to medical debt (Exhibit 3.8).