The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States that Do Not Expand Medicaid – An Update – Issue Brief – 8659-03

One of the major coverage provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) is the expansion of Medicaid eligibility to nearly all low-income individuals with incomes at or below 138 percent of poverty ($27,724 for a family of three in 20151). This expansion fills in historical gaps in Medicaid eligibility for adults and was envisioned as the vehicle for extending insurance coverage to low-income individuals, with premium tax credits for Marketplace coverage serving as the vehicle for covering people with moderate incomes. While the Medicaid expansion was intended to be national, the June 2012 Supreme Court ruling essentially made it optional for states.

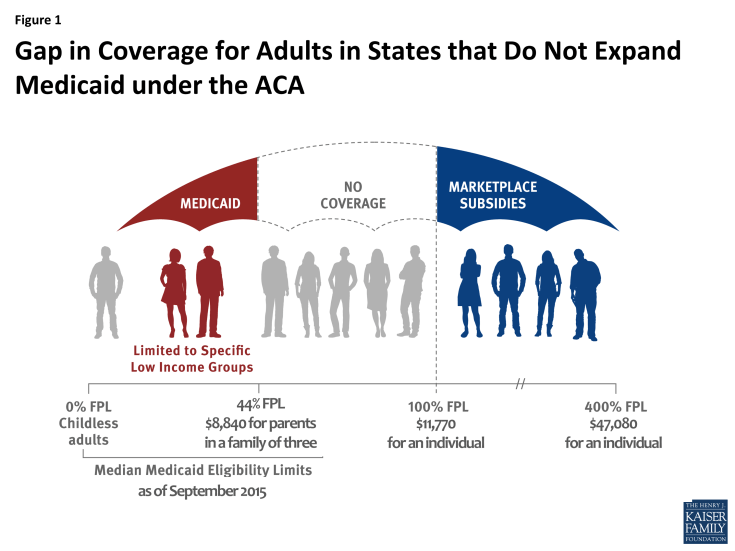

As of September 2015, 20 states were not expanding their programs. Medicaid eligibility for adults in states not expanding their programs is quite limited: the median income limit for parents in 2015 is just 44% of poverty, or an annual income of $8,840 a year for a family of three, and in nearly all states not expanding, childless adults will remain ineligible.2 Further, because the ACA envisioned low-income people receiving coverage through Medicaid, it does not provide financial assistance to people below poverty for other coverage options. As a result, in states that do not expand Medicaid, many adults will fall into a “coverage gap” of having incomes above Medicaid eligibility limits but below the lower limit for Marketplace premium tax credits (Figure 1).

This brief presents estimates of the number of people in non-expansion states who could have been reached by Medicaid but instead fall into the coverage gap, describes who they are, and discusses the implications of them being left out of ACA coverage expansions. An overview of the methodology underlying the analysis can be found in the Methods box at the end of the report, and more detail is available in the Technical Appendices available here.

How Many Uninsured People Who Could Have Been Eligible for Medicaid Are in the Coverage Gap?

Nationally, more than three million3 poor uninsured adults fall into the “coverage gap” that results from state decisions not to expand Medicaid, meaning their income is above current Medicaid eligibility but below the lower limit for Marketplace premium tax credits. These individuals would have been newly-eligible for Medicaid had their state chosen to expand coverage.

Adults left in the coverage gap due to current state decisions not to expand Medicaid are spread across the states not expanding their Medicaid programs but are concentrated in states with the largest uninsured populations. A quarter of people in the coverage gap reside in Texas, which has both a large uninsured population and very limited Medicaid eligibility (Figure 2). Eighteen percent live in Florida, ten percent in Georgia, and eight percent in North Carolina. There are no uninsured adults in the coverage gap in Wisconsin because the state is providing Medicaid eligibility to adults up to the poverty level under a Medicaid waiver.

The geographic distribution of the population in the coverage gap reflects both population distribution and regional variation in state take-up of the ACA Medicaid expansion. As a whole, more people—and in particular more poor uninsured adults— reside in the South than in other regions.4 Further, the South has higher uninsured rates and more limited Medicaid eligibility than other regions.5 Southern states also have disproportionately opted not to expand their programs, and more than half (11 out of 20) of the states not expanding Medicaid are in the South. These factors combined mean 90% of people in the coverage gap reside in the South (Figure 2).

What Are Characteristics of People in the Coverage Gap?

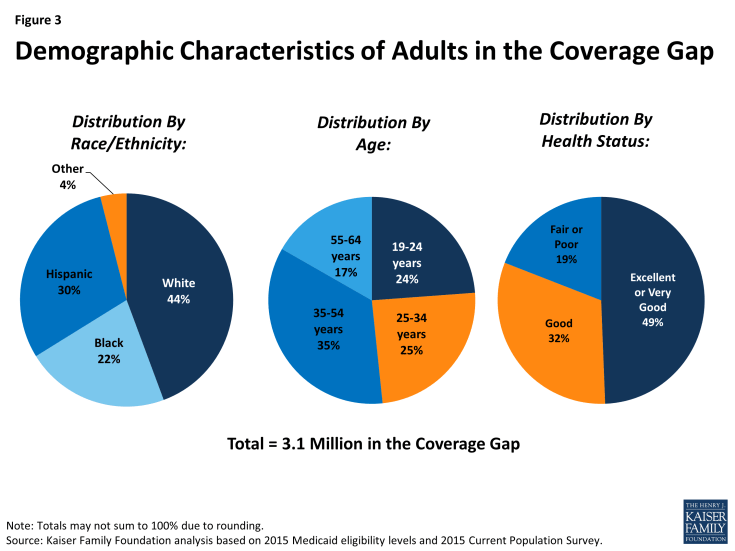

The characteristics of the population that falls into the coverage gap largely mirror those of poor uninsured adults. For example, because racial/ethnic minorities are more likely than White non-Hispanics to lack insurance coverage and are more likely to live in families with low incomes, they are disproportionately represented among poor uninsured adults and among people in the coverage gap. Nationally, 44% of uninsured adults in the coverage gap are White non-Hispanics, 30% are Hispanic, and 22% are Black (Figure 3). However, the race and ethnicity of people in the coverage gap also reflects differences in the racial/ethnic composition between states moving forward with the Medicaid expansion and states not planning to expand. Several states that have large Black populations (e.g., Florida, Georgia, and Texas) have not expanded Medicaid under the ACA. As a result, Blacks account for a slightly higher share of people in the coverage gap compared to the total poor adult uninsured population. The racial/ethnic characteristics of the population in the coverage gap vary widely by state, mirroring the underlying characteristics of the state population.

Nonelderly adults of all ages fall into the coverage gap (Figure 3). Notably, over half are middle-aged (age 35 to 54) or near elderly (age 55 to 64). Adults of these ages are likely to have increasing health needs, and research has demonstrated that uninsured people in this age range may leave health needs untreated until they become eligible for Medicare at age 65.6

While nearly half of people in the coverage gap report that their health is excellent or very good, nearly a fifth (19%) report that they are in fair or poor health (Figure 3). These individuals have known health problems that likely require medical attention. Studies repeatedly demonstrate that the uninsured are less likely than those with insurance to receive preventive care and services for major health conditions and chronic diseases.7 When they do seek care, the uninsured often face unaffordable medical bills.8

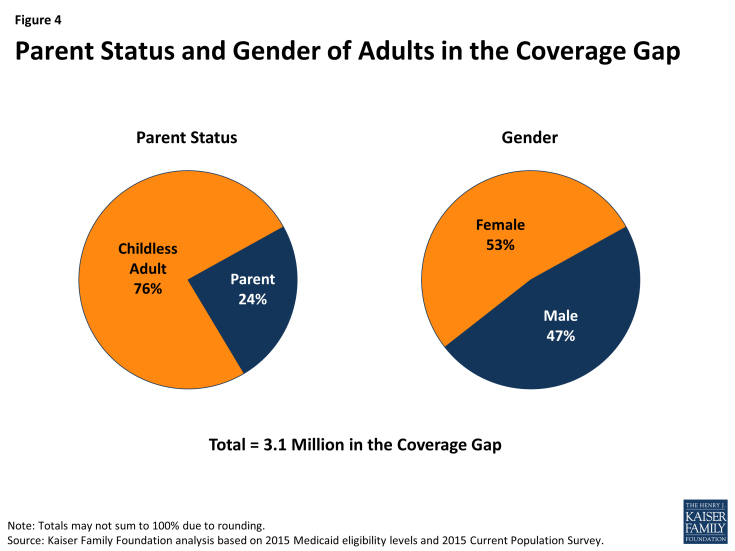

The characteristics of people in the coverage gap also reflect Medicaid program rules in states not expanding their programs. Because non-disabled adults without dependent children are ineligible for Medicaid coverage in most states not expanding Medicaid, regardless of their income, adults without dependent children account for a disproportionate share of people in the coverage gap (76%) (Figure 4). Still, nearly a quarter (24%) of people in the coverage gap are poor parents whose income places them above Medicaid eligibility levels. About a quarter of a million uninsured children have a parent in the coverage gap (data not shown). Research has found that parent coverage in public programs is associated with higher enrollment of eligible children,9 so these children may be hard to reach if their parents continue to be ineligible for coverage. The share of people in the coverage gap who are adults without dependent children (versus parents) varies by state (see Table 1) due to variation in current state eligibility. For example, Maine covers all parents up to at least poverty, so all people in the coverage gap in that state are adults without dependent children.

Even though women are more likely than men to qualify for Medicaid in states not expanding their programs, women account for slightly more than half (53%) of adults in the coverage gap (Figure 4). This pattern occurs because women make up the majority of poor uninsured adults in states not expanding their programs.

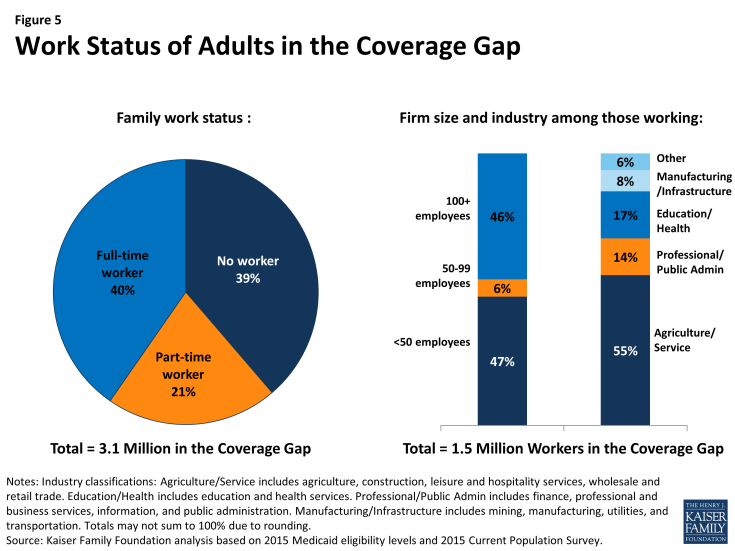

The work status of people in the coverage gap indicates that there are limited coverage options available for people in this situation. More than six in ten (61%) people in the coverage gap are in a family with a worker, and half are working themselves (Figure 5). While workers could potentially have an offer of coverage through their employer, nearly half of workers in the coverage gap (47%) work for small firms (<50 employees) that are not subject to ACA penalties for not offering coverage. Further, many firms do not offer coverage to part-time workers. A majority of workers in the coverage gap also work in industries with historically low insurance rates, such as the agriculture and service industries.

Nearly four in ten (39%) adults in the coverage gap are in a family with no workers. Since the Medicaid expansion was designed to reach those left out of the employer-based system, and because people in the coverage gap by definition are poor, it is not surprising that most are unlikely to have access to health coverage through a job.

What Would Happen if All States Expanded Medicaid?

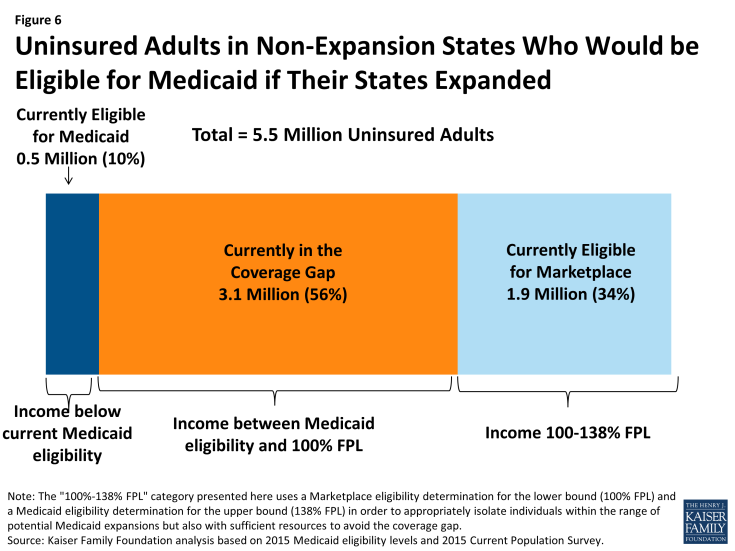

If states that are currently not expanding their programs adopt the Medicaid expansion, all of the 3.1 million adults in the coverage gap would gain Medicaid eligibility. In addition, 1.9 million adults who are currently eligible for Marketplace coverage (those with incomes between 100 and 138% of poverty10) would also gain Medicaid eligibility (Figure 6 and Table 2). Though most of these adults are eligible for tax credits to purchase Marketplace coverage,11 Medicaid coverage may provide lower premiums or cost-sharing than they would face under Marketplace coverage.

A small number (a little more than 500,000) of uninsured adults in non-expansion states are already eligible for Medicaid under eligibility pathways in place before the ACA. If all states expanded Medicaid, those in the coverage gap and those who are instead eligible for Marketplace coverage would bring the number of uninsured adults eligible for Medicaid to 5.5 million people. The potential scope of Medicaid varies by state (Table 2).

Figure 6: Uninsured Adults in Non-Expansion States Who Would be Eligible for Medicaid if Their States Expanded

Discussion

The ACA Medicaid expansion was designed to address the high uninsured rates among low-income adults, providing a coverage option for people who had limited access to employer coverage and limited income to purchase coverage on their own. However, with many states opting not to implement the Medicaid expansion, millions of uninsured adults remain outside the reach of the ACA and continue to have limited, if any, option for affordable health coverage: they are ineligible for publicly-financed coverage in their state, most do not have access to employer-based coverage through a job, and all have limited income available to purchase coverage on their own.

The majority of people in the coverage gap are in poor working families—that is, either they or a family member is employed either part-time or full-time but still living below the poverty line. Given the characteristics of their employment, it is likely that many will continue to lack access to coverage through their job even with ACA provisions for employer responsibility for coverage are effective in 2016.12 Further, even if they do receive an offer from their employer that meets ACA requirements, many will find their share of the cost to be unaffordable. Because this population is generally exempt from the individual mandate, and because firms will not face a penalty for these workers remaining uninsured, they will continue to fall between the cracks in the employer-based system.

It is unlikely that people who fall into the coverage gap will be able to afford ACA coverage without financial assistance: in 2015, the national average premium for a 40-year-old non-smoking individual purchasing coverage through the Marketplace was $276 per month for a silver plan and $213 per month for a bronze plan,13 which equates to more than half of income for those at the lower income range of people in the gap and about a quarter of income for those at the higher income range of people in the gap. Further, people in the coverage gap are ineligible for cost-sharing subsidies for Marketplace plans and could face additional out-of-pocket costs up to $6,850 a year if they were to purchase single individual Marketplace coverage. Given the limited budgets of people in the coverage gap, these costs are likely prohibitively expensive.

If they remain uninsured, adults in the coverage gap are likely to face barriers to needed health services or, if they do require medical care, potentially serious financial consequences. Many are in fair or poor health or are in the age range when health problems start to arise, but lack of coverage may lead them to postpone needed care due to the cost. While the safety net of clinics and hospitals that has traditionally served the uninsured population will continue to be an important source of care for the remaining uninsured under the ACA, this system has been stretched in recent years due to increasing demand and limited resources.

Further, the racial and ethnic composition of the population that falls into the coverage gap indicates that state decisions not to expand their programs disproportionately affect people of color, particularly Black Americans. This disproportionate effect occurs because the racial and ethnic composition of states not expanding their Medicaid programs differs from the ones that are expanding. As a result, state decisions about whether to expand Medicaid have implications for efforts to address disparities in health coverage, access, and outcomes among people of color. In addition, the population in the coverage gap shows that, as a result of state decisions not to expand their Medicaid programs, many remaining uninsured under the ACA will reflect the legacy of the system linking Medicaid coverage to only certain categories of people. Many people who fall outside these categories—such as adults without dependent children—still have a need for health coverage. The ACA Medicaid expansion was designed to end categorical eligibility for Medicaid, but in states not implementing the expansion, the vestiges of categorical eligibility will remain.

State decisions about Medicaid expansion have implications for the potential scope of Medicaid under the ACA. If all states expanded their Medicaid programs, eligibility for Medicaid in non-expansion states would grow from just over half a million to 5.5 million. Though some of these people can currently purchase subsidized coverage through the Marketplace, there are advantages and disadvantages to Medicaid and private coverage in different states. For example, enrollees may face higher out-of-pocket costs and limited networks for Marketplace coverage than they would for Medicaid, whereas access to specialist care may be problematic in some state Medicaid programs. In addition, while people can enroll in Medicaid throughout the year, Marketplace enrollment is only available during a limited open enrollment period. Medicaid is designed to provide a safety net of coverage for low-income people, with benefits and provider networks targeted to this population and coverage available throughout the year as people’s circumstances change. There is no deadline for states to opt to expand Medicaid under the ACA, and debate continues in some states about whether to expand. If more states adopt the expansion, the coverage gap will shrink and more low-income adults will gain access to Medicaid eligibility.

Rachel Garfield is with the Kaiser Family Foundation. Anthony Damico is an independent consultant to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

| Table 1: Number and Characteristics of Poor Uninsured Nonelderly Adults in the ACA Coverage Gap,by State | |||||

| State | Number in Coverage Gap | Share in Coverage Gap who Are: | |||

| People of Color |

Adults without Dependent Children |

Female | In a Working Family |

||

| All states not expanding Medicaid |

3,087,000 | 56% | 76% | 53% | 61% |

| Alabama | 139,000 | 46% | 60% | 47% | 64% |

| Florida | 567,000 | 57% | 82% | 50% | 54% |

| Georgia | 305,000 | 74% | 72% | 51% | 57% |

| Idaho | 30,000 | 35% | 72% | 47% | 72% |

| Kansas | 49,000 | NA | 79% | 42% | 77% |

| Louisiana | 192,000 | 64% | 74% | 53% | 56% |

| Maine | 24,000 | NA | 100% | 58% | 88% |

| Mississippi | 108,000 | 52% | 77% | 54% | 58% |

| Missouri | 109,000 | 40% | 69% | 60% | 71% |

| Nebraska | 27,000 | NA | 74% | 63% | 57% |

| North Carolina | 244,000 | 48% | 82% | 53% | 66% |

| Oklahoma | 91,000 | 38% | 73% | 46% | 62% |

| South Carolina | 123,000 | 41% | 90% | 60% | 51% |

| South Dakota | 13,000 | 46% | 80% | 43% | 59% |

| Tennessee | 118,000 | NA | 98% | 47% | NA |

| Texas | 766,000 | 67% | 66% | 55% | 69% |

| Utah | 41,000 | NA | 80% | 41% | 65% |

| Virginia | 131,000 | 52% | 82% | 62% | 65% |

| Wisconsin* | 0 | – | – | – | – |

| Wyoming | 11,000 | NA | 92% | 36% | NA |

| NOTES: * Wisconsin is provides Medicaid eligibility to adults up to the poverty level under a Medicaid waiver. As a result, there is no one in the coverage gap in Wisconsin. NA: Sample size too small for reliable estimate. SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis based on 2015 Medicaid eligibility levels and 2015 Current Population Survey. |

|||||

|

Table 2: Uninsured Adults in Non-Expansion States Who Would be Eligible for Medicaid if Their States Expanded,

by Current Eligibility for Coverage

|

||||

| State | Total | Currently Eligible for Medicaid |

Currently in the Coverage Gap (<100% FPL) |

Currently May be Eligible for Marketplace Coverage (100%-138% FPL^) |

|

All states not

expanding Medicaid

|

5,498,000 | 544,000 | 3,087,000 | 1,867,000 |

| Alabama | 241,000 | NA | 139,000 | 81,000 |

| Florida | 948,000 | 75,000 | 567,000 | 306,000 |

| Georgia | 521,000 | 47,000 | 305,000 | 169,000 |

| Idaho | 48,000 | NA | 30,000 | 16,000 |

| Kansas | 104,000 | NA | 49,000 | 46,000 |

| Louisiana | 292,000 | 30,000 | 192,000 | 71,000 |

| Maine | 44,000 | NA | 24,000 | 14,000 |

| Mississippi | 181,000 | 24,000 | 108,000 | 49,000 |

| Missouri | 173,000 | NA | 109,000 | 58,000 |

| Nebraska | 41,000 | NA | 27,000 | NA |

| North Carolina | 463,000 | NA | 244,000 | 186,000 |

| Oklahoma | 173,000 | 22,000 | 91,000 | 60,000 |

| South Carolina | 224,000 | 36,000 | 123,000 | 66,000 |

| South Dakota | 22,000 | NA | 13,000 | NA |

| Tennessee | 218,000 | NA | 118,000 | 68,000 |

| Texas | 1,314,000 | 80,000 | 766,000 | 468,000 |

| Utah | 91,000 | NA | 41,000 | 40,000 |

| Virginia | 266,000 | NA | 131,000 | 119,000 |

| Wisconsin* | 113,000 | 86,000 | – | 26,000 |

| Wyoming | 18,000 | NA | 11,000 | 6,000 |

| NOTES: * Wisconsin is provides Medicaid eligibility to adults up to the poverty level under a Medicaid waiver. As a result, there is no one in the coverage gap in Wisconsin. ^ The “100%-138% FPL” category presented here uses a Marketplace eligibility determination for the lower bound (100% FPL) and a Medicaid eligibility determination for the upper bound (138% FPL) in order to appropriately isolate individuals within the range of potential Medicaid expansions but also with sufficient resources to avoid the coverage gap. NA: Sample size too small for reliable estimate. SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis based on 2015 Medicaid eligibility levels and 2015 Current Population Survey. |

||||

Methods

This analysis uses data from the 2015 Current Population Survey (CPS) Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC). The CPS ASEC provides socioeconomic and demographic information for the United Sates population and specific subpopulations. Importantly, the CPS ASEC provides detailed data on families and households, which we use to determine income for ACA eligibility purposes.

The CPS asks respondents about coverage at the time of the interview (for the 2015 CPS, February, March, or April 2015) as well as throughout the preceding calendar year. People who report any type of coverage throughout the preceding calendar year are counted as “insured.” Thus, the calendar year measure of the uninsured population captures people who lacked coverage for the entirety of 2014 (and thus were uninsured at the start of 2015). We use this measure of insurance coverage, rather than the measure of coverage at the time of interview, because the latter lacks detail about coverage type that is used in our model. Based on other survey data, as well as administrative data on ACA enrollment, it is likely that a small number of people included in this analysis gained coverage in 2015.

Medicaid and Marketplaces have different rules about household composition and income for eligibility. For this analysis, we calculate household membership and income for both Medicaid and Marketplace premium tax credits for each person individually, using the rules for each program. For more detail on how we construct Medicaid and Marketplace households and count income, see the detailed technical Appendix A available here.

Undocumented immigrants are ineligible for Medicaid and Marketplace coverage. Since CPS data do not directly indicate whether an immigrant is lawfully present, we draw on the methods underlying the 2013 analysis by the State Health Access Data Assistance Center (SHADAC) and the recommendations made by Van Hook et. al.14,15 This approach uses the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) to develop a model that predicts immigration status; it then applies the model to CPS, controlling to state-level estimates of total undocumented population from Department of Homeland Security. For more detail on the immigration imputation used in this analysis, see the technical Appendix B available here.

Individuals in tax-filing units with access to an affordable offer of Employer-Sponsored Insurance are still potentially MAGI-eligible for Medicaid coverage, but they are ineligible for advance premium tax credits in the Health Insurance Exchanges. Since CPS data do not directly indicate whether workers have access to ESI, we draw on the methods comparable to our imputation of authorization status and use SIPP to develop a model that predicts offer of ESI, then apply the model to CPS. For more detail on the offer imputation used in this analysis, see the technical Appendix C available here.

As of January 2014, Medicaid financial eligibility for most nonelderly adults is based on modified adjusted gross income (MAGI). To determine whether each individual is eligible for Medicaid, we use each state’s reported eligibility levels as of January 1, 2015, updated to reflect state implementation of the Medicaid expansion as of September 2015 and 2015 Federal Poverty Levels.16 Some nonelderly adults with incomes above MAGI levels may be eligible for Medicaid through other pathways; however, we only assess eligibility through the MAGI pathway.17

An individual’s income is likely to fluctuate throughout the year, impacting his or her eligibility for Medicaid. Our estimates are based on annual income and thus represent a snapshot of the number of people in the coverage gap at a given point in time. Over the course of the year, a larger number of people are likely to move and out of the coverage gap as their income fluctuates.

Endnotes

The 2015 federal poverty guideline for a family of three was $20,090. See: http://aspe.hhs.gov/2015-poverty-guidelines.

Of the states not moving forward with the expansion, only Wisconsin provides full Medicaid coverage to adults without dependent children as of 2014. For state-by-state information on Medicaid eligibility, see The Kaiser Family Foundation State Health Facts. “Medicaid Income Eligibility Limits for Adults as a Percent of the Federal Poverty Level.” Data Source: Based on state-reported eligibility levels as of January 1, 2015, collected through a national survey conducted by the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured with the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families. Accessed on October 16, 2015. Available at: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/medicaid-income-eligibility-limits-for-adults-as-a-percent-of-the-federal-poverty-level/

National and state-by-state estimates of the number of people in the coverage gap may change from year to year due to several factors, including differences in the underlying data, small changes in state Medicaid eligibility, and declines in the number of uninsured people by state as economic conditions improve.

Stephens, J., S. Artiga, and J. Paradise. Health Coverage and Care in the South in 2014 and Beyond. (Washington, DC: The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured), April 2014, available at: https://www.kff.org/report-section/health-coverage-and-care-in-the-south-in-2014-and-beyond-health-coverage-and-care-in-the-south-today/

Ibid.

McWilliams JM, Meara E, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. “Use of Health Services by Previously Uninsured Medicare Beneficiaries.” New England Journal of Medicine. 2007 July 12, 357(2): 143-53.

For a review of findings on access to care for the uninsured, see: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. The Uninsured: A Primer. (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation. Available at: https://www.kff.org/uninsured/report/the-uninsured-a-primer/

Ibid.

Sommers BD. “Insuring children or insuring families: do parental and sibling coverage lead to improved retention of children in Medicaid and CHIP?” J Health Econ. 2006 Nov;25(6):1154-69. Epub 2006 Jun 5.

The "100%-138% FPL" category presented here uses a Marketplace eligibility determination for the lower bound (100% FPL) and a Medicaid eligibility determination for the upper bound (138% FPL) in order to appropriately isolate individuals within the range of potential Medicaid expansions but also with sufficient resources to avoid the coverage gap.

The vast majority of these people are eligible for tax credits to subsidize the cost of coverage in the Marketplace, though some (e.g., people with an offer of employer coverage) may not qualify for tax credits.

See http://www.kff.org/infographic/employer-responsibility-under-the-affordable-care-act/ for a review of these requirements.

The methods for arriving at this estimate can be found on the Kaiser Family Foundation Subsidy Calculator, (available here: http://www.kff.org/interactive/subsidy-calculator/).

State Health Access Data Assistance Center. 2013. “State Estimates of the Low-income Uninsured Not Eligible for the ACA Medicaid Expansion.” Issue Brief #35. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota. Available at: http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2013/rwjf404825

Van Hook, J., Bachmeier, J., Coffman, D., and Harel, O. 2015. “Can We Spin Straw into Gold? An Evaluation of Immigrant Legal Status Imputation Approaches” Demography. 52(1):329-54.

Based on state-reported eligibility levels as of January 1, 2015. Eligibility levels are updated to reflect state implementation of the Medicaid expansion as of September 2015 and 2015 Federal Poverty Levels, but may not reflect other eligibility policy changes since January 2015. The Kaiser Family Foundation State Health Facts. Data Source: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured with the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families: Modern Era Medicaid: Findings from a 50-State Survey of Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost-Sharing Policies in Medicaid and CHIP as of January 2015, Kaiser Family Foundation, January 20, 2015.

Non-MAGI pathways for nonelderly adults include disability-related pathways, such as SSI beneficiary; Qualified Severely Impaired Individuals; Working Disabled; and Medically Needy. We are unable to assess disability status in the CPS sufficiently to model eligibility under these pathways. However, previous research indicates high current participation rates among individuals with disabilities (largely due to the automatic link between SSI and Medicaid in most states, see Kenney GM, V Lynch, J Haley, and M Huntress. “Variation in Medicaid Eligibility and Participation among Adults: Implications for the Affordable Care Act.” Inquiry. 49:231-53 (Fall 2012)), indicating that there may be a small number of eligible uninsured individuals in this group. Further, many of these pathways (with the exception of SSI, which automatically links an individual to Medicaid in most states) are optional for states, and eligibility in states not implementing the ACA expansion is limited. For example, the median income eligibility level for coverage through the Medically Needy pathway is 15% of poverty in states that are not expanding Medicaid, and most states not expanding Medicaid do not provide coverage above SSI levels for individuals with disabilities. (See: O’Mally-Watts, M and K Young. The Medicaid Medically Needy Program: Spending and Enrollment Update. (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation), December 2012. Available at: http://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-medicaid-medically-needy-program-spending-and/. And Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, “Medicaid Financial Eligibility: Primary Pathways for the Elderly and People with Disabilities,” February 2010. Available at: http://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-financial-eligibility-primary-pathways-for-the-elderly-and-people-with-disabilities/.