Policy Options to Sustain Medicare for the Future

Section 2: Medicare Payments to Plans and Providers

.

Medicare Advantage

Options Reviewed

This section discusses four sets of options for reducing Federal spending on the Medicare Advantage program:

» Reduce Federal payments by lowering Medicare Advantage plan benchmarks

» Set payments to Medicare Advantage plans through competitive bidding

» Change the risk adjustment methodology

» Reduce or modify quality ratings and bonus payments

Since the 1970s, Medicare beneficiaries have had the option to receive their Medicare benefits through private health plans as an alternative to traditional Medicare. Policymakers have debated the appropriate role and level of payments for private plans in Medicare. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) made changes in the Medicare Advantage program, including reductions in payments and new quality-based bonus payments.

Perspectives on the Medicare Advantage program vary and policymakers arrive at a variety of answers to the following key questions, resulting in different policies for the program:

» Should plans be paid more for enrollees than the per capita costs of the traditional Medicare program, and if so, under what conditions?

» Should plans be rewarded for higher quality ratings (or penalized for lower ratings), and if so, how much, which plans, and under what rating system?

» Should plans be available to all beneficiaries in all parts of the country, and if so, what inducements, if any, should be offered to support plan participation in all areas?

Background

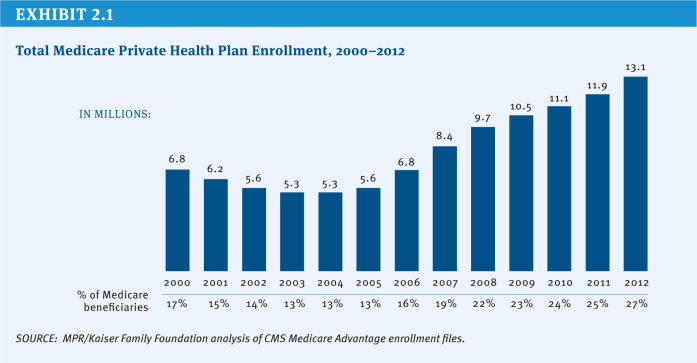

Since 2004, the number of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in private plans has more than doubled from 5.3 million (13 percent of beneficiaries) to 13.1 million (27 percent of beneficiaries) in 2012, with large variations across counties (Exhibit 2.1). In some counties, such as Miami-Dade County in Florida and Multnomah County in Oregon, more than half of beneficiaries were enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan in 2012. In contrast, in other counties, such as Cook County in Illinois and Baltimore County in Maryland, less than 12 percent of beneficiaries were enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan in 2012.

Private plans in the Medicare Advantage program are paid a capitated amount per enrollee to provide all Medicare Part A and B benefits. In addition, Medicare makes a separate payment to plans for providing prescription drug benefits under Medicare Part D (see Section Two, Prescription Drugs for options related to Part D). Since 2006, Medicare has paid plans under a process that compares bids with benchmarks. Plans submit bids based on estimated costs per enrollee for services covered under Medicare Parts A and B. The bids then are compared to benchmark amounts that are set by a formula established in statute and vary by county (or region in the case of regional PPOs), based in part on traditional Medicare costs in the area. The benchmark is the maximum amount Medicare will pay a plan in a given area. If a plan’s bid is higher than the benchmark, enrollees who choose that plan must pay the difference between the benchmark and the bid in the form of a monthly premium (in addition to the Medicare Part B premium). If the bid is lower than the benchmark, the plan and Medicare split the difference between the bid and the benchmark; the plan’s share, known as a “rebate,” varies by the plan’s quality rating and must be used to provide supplemental benefits to enrollees. Medicare payments to plans are then risk adjusted based on enrollees’ risk profiles, including demographic and health status information.

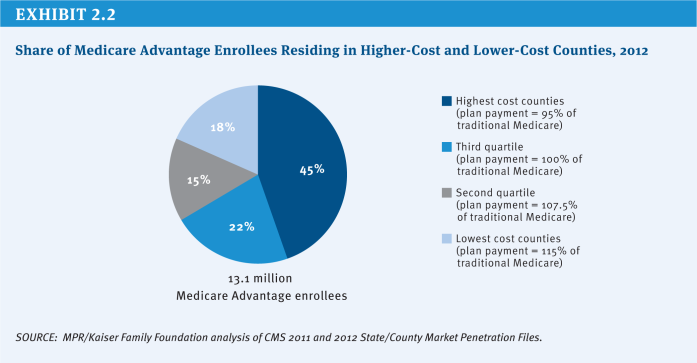

Based on data showing Medicare Advantage plans were being paid, on average, more than the cost of traditional Medicare in their areas, the ACA reduced the benchmarks and tied them to the costs of traditional Medicare in the county, ranging from 95 percent (in high-cost counties) to 115 percent (in low-cost counties) of per capita traditional Medicare spending in the county (see (Exhibit 2.2) for the share of Medicare Advantage enrollees residing in higher-cost and lower-cost counties in 2012). As a result, any changes in the costs of traditional Medicare, such as reductions in payments to providers, directly affect payments to Medicare Advantage plans. The new benchmarks will be phased in between 2011 and 2017, with the length of the phase-in period varying by county; until the new (lower) benchmarks are fully phased in, the benchmarks are a blend between the old and new benchmark. Since January 2012, plans with higher quality ratings have been paid bonus payments, based on provisions in the ACA and a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) demonstration, and are provided a larger rebate than plans with lower quality ratings.

Policy Options

Reduce Federal Payments by Lowering Medicare Advantage Plan Benchmarks

OPTION 2.1

Implement the Affordable Care Act benchmarks for the Medicare Advantage program over a shorter time period

The ACA reduced the benchmarks for all counties, with the transition to the new benchmarks phased in between two and six years (longer transition periods are provided in counties that would experience larger reductions in benchmarks). The majority of beneficiaries (80 percent) reside in counties where the transition will occur over six years. This option would fully implement the new benchmarks established in the ACA by phasing in new benchmarks from 2011 to 2015 rather than from 2011 to 2017, shortening the maximum phase-in period from six years to four years.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option. Implementing the new ACA benchmarks by 2015 rather than 2017 would reduce Medicare spending between 2014 and 2017 for the counties with the longest transition period.

Discussion

Proponents argue this option maintains the payment policies set forth in the ACA but implements the policy on an expedited schedule to achieve savings. Opponents argue that, in the counties with the largest changes in benchmarks, Medicare Advantage plans may not have sufficient time to adjust their care delivery models and business strategies, and thus may be more likely to raise their premiums, limit the benefits they offer, or withdraw from those counties or from the program entirely, requiring beneficiaries to pay more, change plans, or switch to traditional Medicare. The slower transition period may have been implemented to mitigate concerns about the dislocation of beneficiaries resulting from plans withdrawing from the Medicare Advantage program.

OPTION 2.2

Set benchmarks for the Medicare Advantage program equal to local costs of traditional Medicare

The ACA reduced the benchmarks for all counties and tied the benchmarks to the local per capita costs of traditional Medicare, but the benchmarks for some counties will be lower than the local per capita spending for traditional Medicare, while benchmarks for other counties will be higher than the local per capita spending for traditional Medicare. The approach was adopted partly based on research that showed that Medicare Advantage plan costs vary much less geographically than do costs within traditional Medicare (Berenson 2008). However, on a national basis, on average, the new benchmarks are projected to be about equal to local per capita spending for traditional Medicare (MedPAC 2010). Specifically, for the counties in the top quartile of traditional Medicare costs, benchmarks will be 95 percent of traditional Medicare costs, and for the counties in the bottom quartile of traditional Medicare costs, benchmarks will be 115 percent of traditional Medicare costs (MedPAC 2011).

This option would set the benchmark for each county equal to the projected local per capita spending for traditional Medicare. It would increase the benchmarks for the counties in the top quartile of traditional Medicare costs, make no change to the benchmarks for the counties in the second highest quartile of traditional Medicare costs, and reduce the benchmarks for the counties in the third highest and bottom quartiles of traditional Medicare costs. In other words, the reduction in payments to counties with the lowest traditional Medicare costs would be offset by higher payments to counties with the highest traditional Medicare costs.

Budget effects

No current cost estimate is available for this option. Setting the benchmarks equal to local per capita costs of traditional Medicare would produce small savings, if any, once the new ACA benchmarks are fully implemented. In 2008, CBO estimated that setting the benchmarks equal to local per capita costs of traditional Medicare would reduce Federal spending by $157 billion over 10 years (2010–2019), if implemented in 2011; however, this estimate was produced prior to the enactment of the ACA (CBO 2008). Since the new ACA benchmarks are projected to be equal to the costs of traditional Medicare, on average, the actual Federal savings from this option would be small, if any Federal savings were produced.

Discussion

An argument in favor of this option is that Medicare would pay no more for enrollees in Medicare Advantage plans than it would have paid if they had remained in traditional Medicare, regardless of where the enrollee lives. This argument appeals to those who believe the Medicare program should be neutral as to whether beneficiaries decide to enroll in Medicare Advantage plans or traditional Medicare. An argument against this option is that in the counties with lower traditional Medicare costs (which tend to be more rural areas), the reduction in benchmarks could lead Medicare Advantage plans to raise their premiums, limit the benefits they offer, or withdraw from certain regions or from the program entirely, requiring beneficiaries to pay more, change plans, or switch to traditional Medicare.

OPTION 2.3

Set benchmarks equal to local costs of traditional Medicare in counties in which benchmarks for Medicare Advantage plans are higher than local costs of traditional Medicare

The ACA reduced the benchmarks for all counties and tied the benchmarks to the local per capita costs of traditional Medicare, but the benchmarks for some counties will be lower than the local per capita spending for traditional Medicare, while benchmarks for other counties will be higher than the local per capita spending for traditional Medicare.

This option would set the benchmark equal to the projected local per capita spending for traditional Medicare in counties with benchmarks higher than the local costs of traditional Medicare (Feder et al. 2012). This option would reduce the benchmarks for the counties in the third highest and bottom quartiles of traditional Medicare costs and make no change to the benchmarks for the counties in the top quartile and second highest quartile of traditional Medicare costs. This option is identical to Option 2.2 for counties in which the benchmark is higher than traditional Medicare costs, but differs from Option 2.2 in that it would retain the current law benchmark for counties in the top quartile, with benchmarks equal to 95 percent of traditional Medicare costs.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option. If the benchmarks had been set equal to local per capita costs of traditional Medicare for the counties with benchmarks higher than traditional Medicare costs in 2012, Medicare spending would have been between $2 billion and $4 billion lower in 2012.

Discussion

An argument in favor of this option is that Medicare would pay no more for enrollees in Medicare Advantage plans, and would continue to pay less in one-quarter of counties, than it would have paid if they had remained in traditional Medicare, regardless of where the enrollee lived. This argument appeals to those who believe that private Medicare Advantage plans should be at least as efficient as the traditional Medicare program. Some also argue that this option would promote efficiency in the Medicare Advantage market while reducing Medicare spending. Additionally, some argue that paying plans less than traditional Medicare in some counties could help to counter the findings of some research indicating that plans are selectively enrolling healthier enrollees (MedPAC 2012). However, similar to the effects of Option 2.2 above, an argument against this option is that in the counties in which benchmarks are higher than traditional Medicare costs (which tend to be more rural areas), the reduction in benchmarks could lead plans to raise premiums, cut benefits, or withdraw from certain regions or entirely from the program, requiring beneficiaries to pay more, change plans, or switch to traditional Medicare. This option might preserve choice between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare only for beneficiaries residing in counties with average or higher traditional Medicare costs.

Set Payments to Medicare Advantage Plans Through Competitive Bidding

OPTION 2.4

Establish benchmarks for the Medicare Advantage program through competitive bidding

Under current law, payments to Medicare Advantage plans are based on benchmarks defined under current law, as noted above. This option would use a new approach to determine the benchmarks that would be based solely on the average plan bid in each county, with each plan’s bid weighted by its enrollment in the previous year. The benchmarks established by a competitive bidding process would be subject to a ceiling (no greater than the benchmarks under current law) to ensure that benchmarks and Medicare spending are not inflated by this methodology. Beneficiaries enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan with a bid higher than the benchmark would pay an additional premium. Beneficiaries enrolled in a plan with a bid lower than the benchmark would receive supplemental benefits equal to the value of the difference between the plan bid and the benchmark. Traditional Medicare would not be a bidding plan under this option.

Under current law, beneficiaries enrolled in a plan with a bid lower than the benchmark receive supplemental benefits equal to 75 percent of the difference between the plan bid and the benchmark, and most plans provide some supplemental benefits. Under this option, only the plans with bids lower than the average bid in the county could provide supplemental benefits, but beneficiaries enrolled in those plans would receive supplemental benefits equal to 100 percent of the difference between the plan bid and the benchmark, providing beneficiaries with stronger incentives to enroll in the plans with the lowest bids.

Budget effects

No current cost estimate is available for this option. In 2008, CBO estimated that establishing benchmarks through competitive bidding would reduce Federal spending by $158 billion over 10 years (2010–2019), if the program began in 2012 and assuming benchmarks would be subject to a ceiling no greater than the benchmarks under current law (CBO 2008). However, this estimate was produced prior to the enactment of the ACA, which reduced the benchmarks in the Medicare Advantage program; thus, the actual savings from competitive bidding, if fully implemented in 2012, would be smaller.

Discussion

Proponents of this option believe it could lower benchmarks and increase price competition among plans, encouraging plans to obtain larger discounts from providers, provide supplemental benefits valued by beneficiaries, and manage care more efficiently. An argument against this option is that it would reinforce an uneven playing field between private plans and traditional Medicare, but in this case favoring traditional Medicare, especially in high-cost areas, by not requiring it to compete with private plans and improve its efficiency. For example, plans with bids above the benchmark would be required to charge beneficiaries an additional premium, even if the bid was lower than the average per capita costs of traditional Medicare in the county, providing beneficiaries a financial incentive to enroll in either traditional Medicare or a lower cost private plan. Over time, this option could lead some higher-cost plans to withdraw from the Medicare Advantage program, thereby reducing the number of private plans available to beneficiaries.

Demonstrations of competitive bidding among Medicare private plans have not been fully implemented in the past due to objections to traditional Medicare not being included as a plan bid and general opposition among stakeholders. Future attempts to implement competitive bidding in Medicare Advantage could encounter these issues as well, or different concerns may arise in a different environment. A similar option that included traditional Medicare as a plan bid would closely resemble an option for a premium support system (see Section Four, Premium Support).

Change the Risk Adjustment Methodology

Currently, Medicare prospectively adjusts payments to Medicare Advantage plans to reflect the expected costs and health risks of each enrollee. This risk adjustment is intended to compensate plans for enrolling sicker and more costly enrollees, and avoid overpaying plans that enroll healthier than average enrollees. Results from some studies have indicated that plans might be selecting against sicker beneficiaries, particularly within categories of diagnoses, suggesting that the current risk adjustment system may not be adequate (Brown et al. 2011; MedPAC 2012). Studies have also suggested that the differences in payments between Medicare Advantage plans and traditional Medicare may have actually increased after risk adjustment and led to an eight percent increase in total Medicare spending (Brown et al. 2011). While these findings suggest the need for a fundamental review of the current risk adjustment methodology or consideration of a payment approach that reduces the impact of favorable selection, such as partial capitation, by which some of the payment would be based on Medicare Advantage plans’ actual costs, there is still room to improve the current risk adjuster. The option below would make modifications to the existing risk adjustment system.

OPTION 2.5

Improve the risk adjustment system for Medicare Advantage plans

Under the current risk adjustment system for Medicare Advantage, each plan enrollee is assigned a risk score (with average risk equal to 1.0) based on relative health risk, which includes demographics and diagnoses based on the prior year of medical claims, as well as disabilities, institutional status and Medicaid status. The current model for adjusting Federal payments to plans for the health risk of their enrollees explains about 11 percent of the variation in Medicare spending (Pope et al. 2004). Research indicates that providers often do not consistently code conditions on claims from year to year. For example, a primary care provider may indicate on medical claims that a patient has diabetes when initially diagnosed, but might not indicate it on the following year’s claims if the patient’s diabetes is well-controlled and did not require medical attention. This inconsistency in coding of conditions results in greater fluctuations in risk scores and less stable payments to plans (MedPAC 2012). Several researchers, including MedPAC, have concluded that using two years of medical claims data would make the risk scores more stable and would improve the predictive accuracy of the risk adjustment model, particularly for beneficiaries with mental illness and beneficiaries with five or more chronic conditions (Frogner et al. 2011; MedPAC 2012).

This option would require CMS to use two years of historical medical claims data, rather than one year, and to include the number of medical conditions, to adjust the payments to Medicare Advantage plans for the demographics and health history of each plan enrollee. Because two years of diagnosis data would not be available for beneficiaries in their first or second year of Medicare eligibility, the current risk adjustment methodology could be used for these beneficiaries.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option. Using two years of medical claims data (when available) rather than one year and including the number of medical conditions in the risk adjustment model would increase payments for some Medicare Advantage plan enrollees and decrease payments for other enrollees. The option could reduce Medicare spending if it results in a net reduction in payments to Medicare Advantage plans.

Discussion

An argument in favor of this option is that using two years would help to more accurately identify beneficiaries’ conditions and provide a more stable revenue stream for Medicare Advantage plans by reducing year-to-year fluctuations in beneficiaries’ risk scores. An argument against this option is that it would increase the administrative burden of the Medicare Advantage program for both plans and CMS, while significantly improving the risk scores for only the sickest beneficiaries

Reduce or Modify Quality Ratings and Bonus Payments

OPTION 2.6

Terminate the Quality Bonus Demonstration in 2013

The ACA authorized plans with 4 or more stars to receive bonuses of 5 percent added to their benchmark in 2014 and subsequent years, with smaller bonuses for plans receiving 4 stars or 4.5 stars, and 5 percent for plans receiving 5 stars in 2012 and 2013. All Medicare Advantage plans are rated on a 1 to 5 star scale, with 1 star representing poor performance, 3 stars representing average performance, and 5 stars representing excellent performance. The quality scores are based on 53 performance measures, such as whether the plans’ enrollees received the appropriate screening tests, the number of complaints CMS received about the plan, and how enrollees rated the communication skills of the plans’ physicians.

The ACA provided bonuses to about 42 percent of plans in 2012 (Jacobson et al. 2011). In 2012, CMS implemented a demonstration, to take the place of the ACA authorized bonuses, under which plans with 4 or more stars receive bonuses of 5 percent, and plans with 3 and 3.5 stars also receive bonuses of 3 percent and 3.5 percent, respectively, for plan years 2012 through 2014. The demonstration extended the bonus payments to include about 91 percent of plans in 2012. The GAO has recommended terminating the demonstration, and MedPAC has raised concerns about its design and cost (Hackbarth 2011; GAO 2012b). This option would terminate the Quality Bonus Demonstration in 2013 rather than in 2014, which would result in the bonuses to Medicare Advantage plans reverting to the bonuses authorized by the ACA.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option. Medicare savings in 2014 would be less than $3 billion because aggregate bonuses for Medicare Advantage plans that year are expected to be lower than in 2012 ($3 billion). The CMS Office of the Actuary estimated that the total cost of the demonstration will be approximately $8 billion over the three years of the demonstration.

Discussion

Although terminating the demonstration one year early would produce only modest savings, some argue that the demonstration should be terminated because they question the appropriateness of providing bonuses to plans with average ratings (3 or 3.5 stars), and the costs associated with the demonstration. Proponents of the demonstration argue that it encourages and creates more incentives for plans at various quality ratings to maintain or improve their quality ratings.

OPTION 2.7

Restructure quality bonuses to Medicare Advantage plans to be budget neutral

Prior to 2011, plans were “graded on a curve” and scored on a relative scale for each quality measure, resulting in ratings that were relatively normally distributed. Under current law, the bonuses that Medicare Advantage plans receive based on their quality ratings are added to the county benchmark, which increases payments to plans. This option would restructure the quality bonuses to Medicare Advantage plans to be budget neutral, rather than an additional payment to plans, and would adjust the ratings so that the plans were graded on a curve; plans in the top half of the ratings would receive an increase in their benchmarks while plans in the bottom half of the ratings would receive a reduction in their benchmarks, and bonuses would be applied to plans on a sliding scale based on their quality rating.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option. Restructuring the bonus payments to be budget neutral would result in moderate savings by continuing to provide bonuses to half of the plans and reducing payments to the other half of plans. In 2012, Medicare Advantage plans received approximately $4 billion in bonus payments, all of which will be savings if this option is implemented prior to 2015; however, bonus payments will be smaller in 2015 and future years if the CMS demonstration program ends as scheduled at the end of 2014.

Discussion

Proponents argue that this option would reduce Medicare spending while continuing to encourage plans to maintain or improve their ratings. Critics say plans would be rated relative to one another, discouraging collective quality improvements and sharing of quality improvement information among plans. Plans that receive reductions in payments due to relatively low quality ratings may find it difficult to invest financial resources into improving their ratings, which could lead to stagnation in the plan ratings or other fiscal challenges.

OPTION 2.8

Prohibit Medicare Advantage plans from receiving double bonuses in specified counties

The ACA required bonuses to be doubled for plans that are offered in counties with all the following characteristics: (1) lower than average traditional Medicare costs, (2) a Medicare Advantage penetration rate of 25 percent or more as of December 2009, and (3) a designated urban floor benchmark in 2004. In 2012, Medicare Advantage plans in 210 counties qualify for double bonus payments, and the double bonuses accounted for approximately 21 percent of all bonus payments. The rules for the “double bonus counties” were maintained under the Quality Bonus Demonstration. For example, a 5-star plan in a double bonus county has 10 percent added to its benchmark, whereas a 5-star plan in a neighboring county that does not qualify for double bonuses has 5 percent added to its benchmark in 2014.

This option would eliminate the ACA provision that doubles bonuses for plans in specified counties. This would result in all plans with the same quality rating receiving the same bonus percent added to their benchmark.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option.

Discussion

In addition to the savings, an argument for this option is that no objective reason for awarding double bonuses to plans in these counties has been made. Another argument for this option is that it would eliminate inequities across neighboring counties. An argument against this option is that the “double bonus” to the highly rated plans in those counties would help offset the reductions in Medicare Advantage benchmarks resulting from the ACA.

References

Click to expand/collapse

Robert A. Berenson. 2008. “From Politics to Policy: A New Payment Approach in Medicare Advantage,” Health Affairs, March 2008.

Jason Brown, Mark Dugan, Ilyana Kuziemko, and William Woolston. 2011. How Does Risk Selection Respond to Risk Adjustment? Evidence from the Medicare Advantage Program, National Bureau of Economic Research, April 2011.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2008. Budget Options, Volume 1: Health Care, December 2008.

Judy Feder, Stephen Zuckerman, Nicole Cafarella Lallemand, and Brian Biles. 2012. Why Premium Support? Restructure Medicare Advantage, Not Medicare, Urban Institute, September 2012.

Bianca Frogner, Gerard F. Anderson, and Robb A. Cohen. 2011. “Incorporating New Research into Medicare Risk Adjustment,” Medical Care, March 2011.

Government Accountability Office (GAO). 2012a. CMS Should Improve the Accuracy of Risk Score Adjustments for Diagnostic Coding Practices, January 2012.

Government Accountability Office (GAO). 2012b. Medicare Advantage: Quality Bonus Payment Demonstration Undermined by High Estimated Costs and Design Shortcomings, March 2012.

Glenn Hackbarth, Chairman of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. 2011. Letter to Donald Berwick, Administrator for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, January 6, 2011.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). 2010. Presentation by Scott Harrison to the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, “The Medicare Advantage Program: Status Report,” November 4, 2010.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). 2011. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, March 2011.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). 2012. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System, June 2012.

Gregory Pope, John Kautter, Randall P. Ellis, et al. 2004. “Risk Adjustment of Medicare Capitation Payments Using the CMS-HCC Model,” Health Care Financing Review, Summer 2004.

Prescription Drugs

Options Reviewed

This section discusses several options for reducing Medicare spending for prescription drugs in Medicare:1

» Medicare Part D: Provide rebates on prescription drugs used by low-income subsidy recipients enrolled in Part D plans, reduce payments for single-source drugs in Part D, and additional options to make the Part D market more competitive

» Medicare Part B: Change the methodology for determining payment rates for prescription drugs covered under Part B

» Drug approval and patent policy: Accelerate the use of generic and follow-on biologic drugs

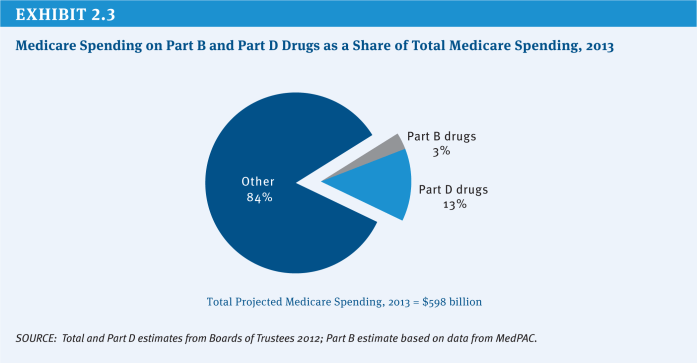

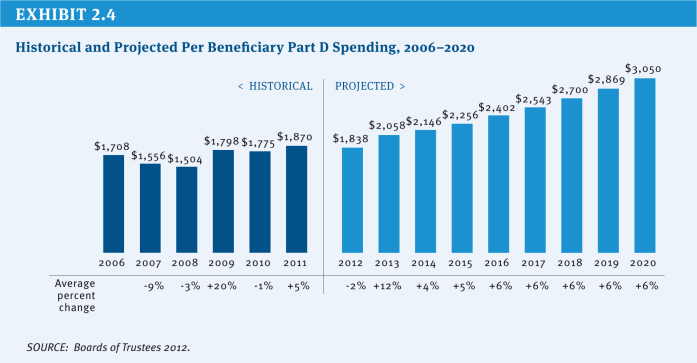

Medicare covers the cost of prescription drugs in both inpatient and outpatient settings. For many years, Medicare has provided inpatient coverage of prescription drugs through Part A and coverage in certain outpatient settings, such as physician offices, outpatient departments, and dialysis facilities, through Part B. In 2006, Medicare added a new voluntary Part D benefit to cover outpatient prescription drugs through private stand-alone prescription drug plans (PDPs) or as part of comprehensive coverage in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans. In 2013, the program is projected to spend $79 billion on Part D outpatient prescription drugs, or about 13 percent of total program spending, and about $20 billion (3 percent of total program spending) on the provision of drugs through Part B (Exhibit 2.3).2 The average annual per capita growth rate on Medicare Part D spending is projected to be 6.5 percent between 2012 and 2020 (Exhibit 2.4). Medicare savings could be achieved by modifying current payment policy for prescription drugs through a variety of approaches.

Background

Med Medicare pays for prescription drugs under Parts A, B, and D. In the case of Part A, Medicare covers prescription drug costs when provided during stays in an inpatient hospital or skilled nursing facility, as well as drugs used in hospice care for symptom control or pain relief. The cost of prescription drugs in these settings generally is covered as part of a bundled prospective payment for services provided in an inpatient setting, thus putting the facility in charge of managing the price and use of drugs.

Medicare Part B covers drugs in several circumstances including: drugs administered under the direct supervision of a physician (such as infusion of chemotherapy drugs), certain oral cancer drugs that are clinical substitutes for physician-administered drugs, and drugs used in conjunction with Medicare-covered durable medical equipment (DME), such as a nebulizer or infusion pump. Most Part B drugs are paid under a system based on an average sales price (ASP). In addition, Medicare Part B covers drugs provided in conjunction with services delivered in hospital outpatient departments or dialysis facilities; these drugs are included as part of larger payment bundles for services provided at these facilities.

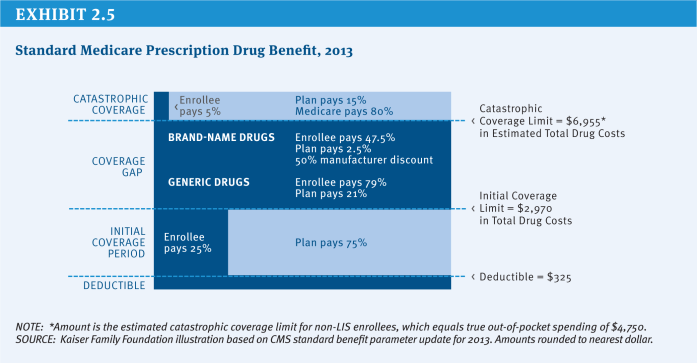

Medicare Part D, the voluntary prescription drug benefit enacted in the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 and implemented in 2006, covers outpatient prescription drugs. Under Part D, Medicare makes payments to private plans—either stand-alone prescription drugs plans (PDPs) or comprehensive Medicare Advantage (MA) plans—to subsidize the cost of the prescription drug benefit for enrollees. Beneficiaries participating in traditional Medicare may select a PDP for their drug coverage, while those in Medicare Advantage may enroll in the drug plan offered by their Medicare Advantage plan. Basic drug coverage parameters are set in law, but participating plans have flexibility to manage a formulary, employ tiered cost sharing and other utilization management techniques, and create networks of participating pharmacies (all within a set of Federal guidelines) (Exhibit 2.5). Federal subsidies to the plans cover 74.5 percent of the cost of the average plan. Enrollees selecting more expensive plans pay the higher cost above the average bid, while those selecting less expensive plans pay less.

Policy Options

Medicare Part D

OPTION 2.9

Require manufacturers to pay a minimum rebate on drugs covered under Medicare Part D for beneficiaries receiving low-income subsidies

The price paid for a Medicare Part D drug is determined through negotiation between private drug plans that administer the benefit and the manufacturer of the drug. By contrast, drug prices in the Medicaid program are based on a rebate system. For any drug covered in Medicaid, the manufacturer pays a rebate to the Federal government (shared with the states) defined as the lesser of a minimum amount or an amount based on the best price paid by private purchasers, with an additional rebate if the drug’s price increases faster than general inflation. Prior to the introduction of Part D in 2006, Medicaid covered prescription drugs for beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, with drug prices subject to the rebate system. However, beginning in 2006, responsibility for drug costs for dual eligible beneficiaries shifted from Medicaid to Medicare Part D, and Medicaid rebates no longer were required. Part D discounts negotiated by private plans are smaller (averaging about one-third the size) than the rebates received by Medicaid, which means that Medicare pays higher prices than Medicaid would for low-income enrollees (HHS OIG 2011a).

An option to achieve savings in Medicare would be to require manufacturers to pay a minimum rebate on drugs covered under Medicare Part D (including best price and inflation provisions similar to the current system under Medicaid) for Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in the Low-Income Subsidy (LIS) program.

Budget effects

Requiring manufacturers to provide a rebate on all prescription drugs used by low-income beneficiaries is estimated by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) to achieve $137 billion in savings over 10 years (2013–2022) or about $15 billion in the first year of full implementation (CBO 2012a).

Discussion

Advocates of this option argue that it would achieve considerable savings and put the nation’s largest public programs on par when it comes to paying for drugs. Opponents argue that a rebate policy would reduce revenue available for private investment in research and development for new drugs, reduce incentives for manufacturers to offer favorable rebates to private payers, and result in higher prices for new drugs. Opponents also contend that this option would undermine the competitive system used in Part D and lead to higher beneficiary premiums (Antos and King 2011; Holtz-Eakin and Ramlet 2011). Advocates suggest the effects on research and development would be relatively small, and CBO scoring appears to support this perspective (Frank 2012).

OPTION 2.10

Authorize the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to negotiate lower prices for high-cost single-source drugs

Currently, responsibility for Part D drug pricing falls in the domain of the competing private Part D plans that offer the drug benefit to participating beneficiaries. Private drug plans seek to negotiate lower drug prices (both direct retail prices and manufacturer rebates) through decisions about which drugs are on formulary and on preferred formulary tiers. Current law explicitly states that the HHS Secretary “may not interfere with the negotiations between manufacturers and pharmacies and PDP sponsors.” This option would authorize the HHS Secretary to negotiate lower prices for high-cost drugs sold by only one manufacturer (i.e., single-source drugs). In addition to direct negotiation by the Secretary, one approach to such negotiation would be a system of binding arbitration (Frank and Newhouse 2008). A third alternative would use a mandated rebate for the same subset of drugs instead of a drug-by-drug negotiation process (similar to Option 2.9).

Budget effects

No current cost estimate is available for this option. In 2007, CBO scored a proposal to remove the current non-interference provision, but retaining the ban on a Federally required formulary, as having a negligible effect on costs. CBO based the lack of scored savings on the premise that the HHS Secretary would have no leverage for negotiation in the absence of any power to require a formulary and thus to obtain discounts in recognition of preferred formulary status. In 2008, CBO reiterated its view but suggested the possibility of small savings “for single-source drugs that had no close substitutes on the market,” where the HHS Secretary might use the power of persuasion to obtain discounts. Similarly, the Secretary could consider requiring plans to use prior authorization for specified drugs for which no discount is provided as part of a negotiation strategy, even in the absence of a national formulary (CBO 2008).

Discussion

Though CBO has cast doubt on the potential for savings with a simple repeal of the non-interference provision, its 2008 statement suggests that a targeted expansion of Federal involvement in pricing can offer savings if it creates true leverage for a negotiation. Private drug plans have the most leverage to obtain discounts on brand-name drugs that face competition from other drugs that treat the same medical condition. In these cases, plans use available tools (such as tiered cost sharing or step therapy) to encourage enrollees to use one particular drug among other options in the drug class. Manufacturers typically offer discounts in recognition of the higher market share for their drug. Private plans are least able to negotiate discounts on brand-name drugs with no real therapeutic alternative, including many of the new, expensive biologic drugs.

Advocates of a Federal role in price negotiation (or a targeted rebate) contend that the government would have greater leverage to obtain better prices on these high-priced drugs. Opponents respond that the higher prices for these new single-source drugs reflect the high cost of developing new drugs and such policies would inhibit research and development.

OPTION 2.11

Authorize the HHS Secretary to administer a Medicare-sponsored Part D plan to compete with private Part D plans

The Medicare prescription drug benefit is provided through a system of competing private plans, which have an incentive to keep premiums down in order to gain a larger share of enrollment. Although the current system relies exclusively on private drug plans, some policymakers have advocated for a government-operated approach to providing drug coverage, in line with the traditional Medicare program.

One option for achieving savings would be to authorize the HHS Secretary to administer a Federally-run Part D plan offered through the Medicare program to compete with private drug plans. Like other Part D plans, this Medicare-sponsored plan would have the authority to establish formularies, use cost-sharing tiers, and apply utilization management tools. This plan could be offered as the default option for beneficiaries who fail to select a plan or for Low-Income Subsidy (LIS) beneficiaries whose current plan no longer qualifies as an LIS “benchmark” plan.3

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option. Savings could be achieved to the extent that the Medicare-sponsored option is able to provide coverage more efficiently than private plans in certain parts of the country or spur greater competition in the Part D marketplace. This would depend on the ability of the Medicare-sponsored option to leverage lower prices, manage utilization more effectively, and operate with fewer administrative expenses than private Part D plans. The likelihood of savings would be reduced if private plans were able to attract healthier and less-expensive beneficiaries than enrollees in the Medicare-sponsored option (beyond the reach of risk-adjustment factors). More specific assessment of the potential cost implications of this option would depend on many design decisions and on projected enrollment.

Discussion

Advocates of a Medicare-sponsored plan suggest that it would have greater negotiating leverage over drug prices and lower administrative costs, which could bring the cost of the Part D benefit down for both beneficiaries and the government. In addition, it might have the ability to test reforms aimed at addressing long-term cost drivers, such as the growth of expensive specialty drugs. Critics of this option contend that a Medicare-sponsored plan would have less latitude to adopt formulary and utilization management approaches than private plans, which could limit its ability to obtain discounts on drug prices. If true, enrollment might remain modest and the plan’s impact on costs would be minimal.

OPTION 2.12

Authorize the HHS Secretary to engage in a competitive bidding approach that excludes plans with relatively high bids or poor quality

The competitive model for Medicare Part D achieves lower costs when competing plans reduce costs—and thus beneficiary premiums—by managing utilization and negotiating for low drug prices. If beneficiaries regularly shop for lower premiums and total out-of-pocket costs, plans have a greater incentive to keep costs low. Evidence suggests that many Part D enrollees have not been selecting the optimal plan for their particular drug needs and that many enrollees do not reconsider their plan choice on a regular basis (Polinski et al. 2010; Abaluck and Gruber 2011; Zhou and Zhang 2012). Both factors tend to reduce the incentives for plans to compete vigorously for plan enrollment and to minimize total spending.

Medicare could increase incentives for plan competition by replacing the current “all-comers” approach with a system of competitive bidding, whereby low-quality plans or plans that bid too high are excluded from the program (Rice and Cummings 2010). To minimize disruption, plans with winning bids could remain in Medicare for more than a single year.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option.

Discussion

Proponents of a competitive bidding approach contend that it would enhance competition on both cost and quality by requiring plans to compete first for inclusion in the program and then, if they meet the standards of participation, compete for enrollment. A program with fewer plans might also make it easier for beneficiaries to review their choices and to make more optimal selections. On the other hand, excluding potential competitors could reduce the scope of competition and eliminate the best plan option for some beneficiaries.

OPTION 2.13

Reduce reinsurance payments to Part D plans

Part D includes several mechanisms by which the Medicare program partially offsets the insurance risk faced by Part D plan sponsors:

» A risk-adjustment system for the capitated payments made by Medicare to Part D plans;

» Reinsurance payments to plans whereby Medicare pays 80 percent of the cost of covered benefits for any individual enrollee with drug spending above the catastrophic coverage threshold; and

» Risk-sharing corridors under which Medicare shares unanticipated losses (and profits) incurred by plans.

Federal reinsurance payments for high-cost users totaled an estimated $13 billion in 2011, or 22 percent of Federal Part D costs. About 9 percent of Part D enrollees had spending in 2010 high enough to reach the catastrophic phase of the Part D benefit—the point at which 95 percent of costs are partially paid by Federal funds (80 percent directly as reinsurance and 15 percent by the plans, but with Federally subsidized premium dollars). Spending incurred by these beneficiaries represents 44 percent of total drug costs for Part D enrollees (MedPAC 2012a). One option to achieve savings would be to reduce by half the Federal reinsurance payments to Part D plans for costs above the catastrophic coverage threshold—from 80 percent to 40 percent, with 55 percent paid by the plans (up from 15 percent under current law).

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option. A reduction of reinsurance payments would not directly reduce Federal spending because total Federal subsidies, as 74.5 percent of plan costs, are divided between direct premium subsidy amounts and reinsurance payments; if reinsurance payments are lower, then the direct premium subsidy is higher. However, Federal savings would be achieved if the reduction of reinsurance increases the incentives for plans to manage utilization by these high-cost users and if plans successfully implement more effective management. In that case, the resulting savings would be shared by the plans and the Federal government in future-year premium bids and in risk-sharing payments.

Discussion

Reinsurance blunts incentives for plans to manage the costs of high-spending enrollees by making the government responsible for the vast majority of costs for enrollees who exceed the catastrophic cost threshold. With only 15 percent exposure for high-cost users, plans may be less likely to invest resources in efforts to manage the drug costs of these enrollees. To the extent that plans continue to receive full manufacturer rebates for drugs purchased by these enrollees, plan incentives to manage drug use are further blunted. In some situations, rebate revenue may actually offset the plan’s cost for brand drugs in the catastrophic phase. A substantial reduction in the reinsurance share could significantly increase plan incentives to manage costs.

Plans, however, may argue that tools for managing many high-cost enrollees are limited, especially because the choice of treatment options is driven by physicians with whom they lack any contractual relationship (which is particularly the case for stand-alone PDPs). In addition, an original reason for including reinsurance payments in the system was to protect plans from the consequences of adverse selection—although this proposal would leave the protections of risk adjustment and risk-sharing corridors in place. If plans perceive higher risk, they may increase premiums or take steps to avoid the most risky enrollees.

OPTION 2.14

Encourage plans to expand the use of generic drugs

Generic drugs accounted for 75 percent of all prescriptions paid for by Part D in 2010 but just 25 percent of Part D spending.4 Use of generics saved Medicare $33 billion in 2007 (CBO 2010). Patent expirations for popular brand-name drugs provide opportunities for Medicare and other payers to achieve additional savings. To encourage use of generics, plans use tiered cost sharing, step therapy, and other utilization management approaches. Additional steps could be taken to increase use of generic drugs in Part D.

OPTION 2.14A

Increase the differential between generic and brand drug copayments in drug classes where generics are broadly available

One option to achieve savings would be to increase the differential in copayments between generic and brand drugs in drug classes where generics are broadly available. There is some evidence that a zero copayment for generics creates a much stronger incentive than does a low copayment. Although some plans now apply a large copayment differential and some set the generic copayment at zero, CMS could modify the guidance to plans that use tiered cost sharing to encourage larger differentials or lower copayment levels for generic drugs, or create incentives (e.g., through performance measures) to increase generic use. In addition, nondiscrimination rules that currently disallow differential cost-sharing policies for drugs used to treat different medical conditions could be modified to allow variations in cost sharing based on the availability of generics in a particular class of drugs.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option. Using 2007 data, CBO has projected additional savings of nearly $1 billion if all prescriptions for multiple-source brand-name drugs had been filled with generics and another $4 billion with increased therapeutic substitution in seven drug classes (CBO 2010).

Discussion

Advocates point to evidence that plans can use different cost-sharing structures, especially lower copayments for generics and higher copayments for brands, to increase incentives to substitute generic drugs and achieve savings (Hoadley et al. 2012). Sharper financial incentives may encourage more patients to use generics. However, a concern with this option is that it could impair access and outcomes for patients whose clinical response to a generic drug is less than optimal, although this concern could be addressed if effective exceptions processes are guaranteed in these cases. Some have expressed concern that reduced use of brand-name drugs would lower returns on these drugs and thus weaken incentives for research associated with pharmaceutical innovation.

OPTION 2.14B

Increase the differential between generic and brand drug copayments for Low-Income Subsidy Part D enrollees in drug classes where generics are broadly available

For LIS enrollees, copayments are set in law (and updated annually by an indexing formula) and not subject to modification by plans. In 2013, some LIS enrollees (depending on income and eligibility status) are charged a $1.15 copayment for generic subscriptions and a $3.50 copayment for brands, while most others are charged $2.65 and $6.60, respectively. This may help explain why the rate of generic use for LIS enrollees is lower than that for non-LIS enrollees. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) has recommended increasing the differential in copayments between generic and brand drugs in drug classes where generics are broadly available (MedPAC 2012c). The Commission offered an example of $0 for generics, $6 for preferred brand drugs, and a potentially higher amount for non-preferred brand drugs. To protect against any adverse impact on access, MedPAC proposed that current exceptions and appeals processes would remain in effect in circumstances where the generic drug is not clinically appropriate, and that the HHS Secretary should monitor utilization for any access problems.

Budget effects

In 2011, MedPAC estimated that its recommendation on drug copays for LIS beneficiaries would lead to a reduction of $17 billion in Federal spending over 10 years (MedPAC 2011). If adherence to medications increases, there could be additional savings as a result of lower use of other medical services.

Discussion

MedPAC suggested that lower generic copayments would lead more LIS beneficiaries to switch to generics, with a resulting reduction in out-of-pocket costs that could in turn increase access and adherence to medications (MedPAC 2012c). The decreased costs experienced by plans would help to lower premiums and Federal subsidy payments. As with options to increase generic use for non-LIS beneficiaries, this option could reduce access if exceptions processes prove inadequate. MedPAC highlighted the importance of an effective exceptions and appeals process to protect beneficiary access. The option could also lower returns on brand-name drugs and thus weaken incentives for pharmaceutical innovation.

OPTION 2.15

Strengthen incentives for adherence

Although Part D plans are responsible for managing drug utilization and have a financial incentive to keep drug costs low, stand-alone prescription drug plans do not gain or lose money based on the cost or savings for non-drug services that may be a result of drug use. When beneficiaries receive drug benefits through Medicare Advantage plans, the incentives are better aligned. A small but growing body of literature suggests that greater adherence leads to lower use of health services and potentially better health outcomes (Osterberg and Blaschke 2005; McWilliams et al. 2011; Stuart et al. 2011; Jha et al. 2012).

Savings could be achieved by strengthening incentives for medication adherence. Options include: (1) lowering cost sharing for specific drugs, (2) targeted beneficiary education, (3) engagement of physicians or pharmacists in addressing non-adherence issues, (4) performance measures for drug plans aimed at adherence, and (5) broader systemic solutions involving medication adherence in initiatives such as accountable care organizations.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option. Increased adherence to drug regimens will likely increase spending for drugs in Part D. However, CBO recently concluded that it could attribute Part A or Part B savings based on increased drug use. In general, the agency finds that a 1 percent increase in prescription drug use results in a reduction in spending for medical services of about one-fifth of 1 percent (CBO 2012b).

Discussion

Proponents suggest that various factors can increase adherence and that different approaches may work for different patients and different disease states. Several studies show that lower cost sharing (including implementation of value-based insurance design) and more use of generic drugs are associated with increased adherence. But financial incentives may not be the entire solution, and targeted beneficiary education initiatives could play a role. The involvement of both physicians and pharmacists can help address some issues of non-adherence, and initiatives such as patient-centered medical homes or accountable care organizations could incorporate a focus on medication adherence. In addition, electronic health records could offer tools for tracking adherence and offering physicians and other clinicians more opportunities to counsel patients. CMS could take specific actions to strengthen incentives, including improved performance measures for both stand-alone PDPs and Medicare Advantage drug plans to increase adherence. For example, plans could be encouraged to implement elements of value-based insurance design, such as eliminating copayments for selected drug classes or for selected high-value drugs where adherence is critical. Critics may question whether the added direct costs associated with greater medication adherence would be fully offset by savings for hospital and physician care.

OPTION 2.16

Strengthen medication therapy management programs

In 2010, about 9 percent of Part D enrollees (about 2.3 million enrollees) had spending high enough to reach the catastrophic phase of the Part D benefit, meaning they had at least $6,440 in total Part D drug costs in that year. Spending by these beneficiaries represented 44 percent of total Part D drug spending. Most of these costs are paid with Federal dollars (MedPAC 2012a). In part to address the unique needs of people with high drug needs, all Part D plans are required to operate medication therapy management (MTM) programs that focus on beneficiaries with high drug costs, large numbers of drugs, or multiple chronic conditions. As of 2010, 2.6 million of 3 million eligible enrollees were participating in MTM programs (MedPAC 2012c).

Although all plans have created MTM programs, evidence on their effectiveness is limited. CMS is collecting data on plan MTM programs and conducting an evaluation of them, with results due in 2013. Evaluation results could help policymakers identify specific steps to increase the effectiveness of MTM programs. The original intent behind MTM programs was to improve medication use and to reduce adverse events that may result when beneficiaries take multiple medications. If properly designed, MTM programs could reduce unnecessary utilization of drugs by those taking multiple drugs, while also increasing adherence with the important drugs for a person’s condition. MTM programs could also focus on appropriate use of high-cost drugs. Steps to increase the effectiveness of MTM programs could include stronger incentives for beneficiaries, physicians, and pharmacists to participate, for example, reduced cost sharing if MTM participants undergo comprehensive medication reviews, or adding MTM provided by physicians or pharmacists as a covered Part B service. CMS could consider incorporating MTM programs into its shared savings programs for accountable care organizations. CMS also could consider improved performance measures related to MTM programs (Rucker 2012).

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option. With Part D spending for 2013 projected at $79 billion, the highest-cost Part D enrollees will represent about 44 percent, or $35 billion, in spending. If costs for these enrollees were reduced even 10 percent, it would represent at least $3 billion in annual savings. Greater savings could be achieved if MTM programs result in less medical spending, such as for adverse drug-related hospitalizations (Budnitz et al. 2011).

Discussion

MTM program advocates emphasize improved safety and clinical outcomes as the most important results of effective MTM, and they can point to successful examples of such programs outside of Part D. Many of these exemplar programs can point to a return on investment through both lower medication costs and medical and hospital costs. Concern about the growth of these programs includes the possibility that up-front spending to operate the programs may not realize savings (MedPAC 2009). In addition, some enrollees may find the programs impose an undue burden and make it more difficult to access to needed medications.

OPTION 2.17

Repeal provisions in the Affordable Care Act that would close the Part D coverage gap by 2020

The original design of Part D included a coverage gap (between $2,970 and $6,955 in total drug costs in 2013 under the standard benefit design), in which beneficiaries were responsible for paying all drug costs out of pocket. Beneficiaries with costs that exceed the gap are then eligible for catastrophic coverage, in which the Federal government pays 95 percent of drug costs. The ACA phases out the coverage gap by 2020 through a combination of mandated lower manufacturer prices for brand drugs and gradually reduced beneficiary cost sharing. Repeal of the ACA—or of these specific provisions—would reduce Federal spending and shift those costs back to beneficiaries.

Budget effects

CBO has estimated that the provisions closing the gap result in an additional $86 billion in new Federal spending over 10 years, partially offset by $35 billion in reductions on other medical services under Medicare, for a net increase of $51 billion over 10 years (2013–2022). Legislation restoring the coverage gap would recoup that spending, but savings could be reduced if the Federal government had to repay discounts already provided by manufacturers (CBO 2012b).

Discussion

Proponents of repeal argue that the Federal government cannot afford additional entitlement spending at a time of large annual deficits and a growing national debt. Opponents say repeal would lower Federal spending but only by shifting costs back to Part D enrollees with relatively high drug costs. This also could lead some beneficiaries to skip drugs or take reduced doses, leading to higher medical costs.

Medicare Part B

OPTION 2.18

Lower the percentage paid by Medicare for Part B drugs from 106 percent to 103 percent of the average sales price

Since 2005, Medicare payments for many drugs covered under Part B—primarily injectable or intravenous products administered by a physician—are based on an average sales price (ASP) methodology. The ASP is based on sales data submitted to CMS by drug manufacturers, excluding sales under various government programs, and reflects the price net of various discounts and rebates. Medicare Part B drug payments are set at 106 percent of the ASP since not all providers can obtain the drug at the average price. Prior to 2005, Medicare paid providers at a rate equal to 95 percent of the average wholesale price (AWP), and costs were rising rapidly for Medicare and its beneficiaries. Since shifting to the ASP approach, Part B drug spending has increased modestly at 2.7 percent per year, compared with increases of 25 percent per year from 1997 to 2003 (MedPAC 2012a). Under this option, the current payment would be reduced from 106 percent of ASP to 103 percent.

Budget effects

CBO has estimated this option would save $3.2 billion over 10 years.

Discussion

Some have argued that the 6 percent add-on amount is excessive, especially for the most expensive drugs, and that there is no empirical justification for this amount. Furthermore, the percentage-based add-on is much greater for expensive drugs and creates an incentive to select the most expensive brand-name drug among available alternatives. Critics of changing this policy say that the current pricing methodology has done a good job of achieving savings, and that additional adjustments would threaten access to these drugs (Holtz-Eakin and Zhong 2011). Oncology providers also have argued that this option would have the greatest impact on small, community-based practices with the least leverage to negotiate prices with manufacturers. Patients treated by these practices might be referred to hospital outpatient departments for their treatments.

OPTION 2.19

Change from the current average wholesale price (AWP) methodology for certain Part B drugs to the average sales price (ASP) methodology used for other Part B drugs

Although the ASP-based system for setting prices is used for most Part B drugs, several small groups of drugs (drugs administered at home with an infusion pump, immune globulin administered by subcutaneous injection, and preventive vaccines for influenza, pneumococcus, and hepatitis B) are instead paid based on 95 percent of the average wholesale price (AWP). Because the AWP is more of a “list price” that does not incorporate frequently used discounts and rebates, it tends to overstate actual market prices. A 2005 study by the HHS Office of Inspector General (OIG) found that across about 900 brand-name Part B drugs, the ASP was 26 percent lower than the AWP at the median (HHS OIG 2005). Thus, even a 5 percent reduction in payments below AWP levels provides higher reimbursement than would occur using the ASP. Because the AWP generally is regarded as an unreliable indicator of the cost of the drugs listed above, Congress could move these drugs to the ASP system that has proven effective for other Part B drugs.

Budget effects

No cost estimate is available for this option. Total spending in 2010 for Part B drugs administered in physicians’ office or furnished by suppliers was $11.5 billion, of which no more than 5 percent (up to about $0.5 billion) is for drugs paid under the AWP methodology. Ten percent savings would yield savings of up to $500 million over 10 years.

Discussion

A switch to the ASP-based price for this set of Part B drugs, some of which are associated with the use of durable medical equipment, would correct the current payment methodology that appears to produce higher-than-necessary payments for these drugs. One reason for the exclusion of these drugs from using ASP-based prices may have been the intended transition of durable medical equipment to a system of competitive bidding, a reform that still is in progress. Because some drugs in this category have been subject to shortages, some worry that lower prices could exacerbate those shortages because the manufacturers would receive lower returns from production.

OPTION 2.20

Restore the legal authority for CMS to use a “least costly alternative” policy among competing Part B drugs

For some patients, there are multiple therapeutic alternatives available. However, under a system that reimburses physicians based on the sales price of the drug, physicians have no incentive to select a less expensive option. In fact, the 6 percent markup on the ASP may create an incentive to use the more expensive option (HHS OIG 2011). A notable example is the choice between Lucentis and Avastin—two related biologicals used to treat age-related macular degeneration in eyes—that have been shown to produce equivalent results for patients but have very different prices (Rosenfeld 2011; CATT Research Group et al. 2012). A 2011 report by the HHS Office of Inspector General estimated that paying for treatments using Lucentis at the lower Avastin rate would have generated $1.1 billion in savings in 2008–2009 and reduce beneficiary cost sharing by another $275 million (HHS OIG 2011c). A 2012 report by the OIG on drugs used to treat prostate cancer showed savings if the least costly drug in the class was substituted for other similar drugs, with a total one-year savings of $33 million, or 13 percent of the cost of this class of drugs (HHS OIG 2012b).

In the past, Medicare has used a “least costly alternative” policy, where Medicare bases the payment rate for a group of clinically similar services (drugs in this case) on the least costly item in the group. In April 2010, Medicare removed this policy from Part B drugs after a successful challenge in court (relating to inhalation drugs used to treat lung diseases, Zopenex and Duoneb). In 2012, the HHS Office of Inspector General recommended that CMS consider seeking legislative authority to reinstate Medicare’s authority to apply this policy (HHS OIG 2012b).

Budget effects

In 2011, MedPAC reported that restoring the HHS Secretary’s authority to apply a least costly alternative policy would lead to savings of $1 billion in Federal spending over 10 years (MedPAC 2011).

Discussion

Advocates to restore authority to use the “least costly alternative” policy argue that the current policy creates a financial incentive for providers to choose the more expensive drug. Restoring the “least costly alternative” policy could level the financial incentives and encourage physicians to select a therapy based on clinical and safety considerations. They also point out that beneficiaries would save money through reduced cost sharing.

Critics raise concerns that it would put CMS in the position of determining when treatments are similar enough to be used interchangeably without the benefit of a full array of clinical studies. In particular, some critics point out that the full value of a new, more expensive drug may not be immediately apparent when it first comes to the market. Limiting payment for the more expensive drug would not only make access to that drug more difficult, but would deny clinicians experience with the new drug that might lead to a better understanding of its clinical benefits.

OPTION 2.21

Require manufacturer discounts or rebates for Part B drugs or allow Medicare to negotiate drug prices for Part B drugs when Medicare purchases account for a large share of spending on a specific drug

Although the ASP methodology generally reflects pricing levels in private-sector transactions, various government purchasers acquire these drugs at lower prices than under Medicare’s rules. One option to address this pricing discrepancy would be to allow Medicare to negotiate drug prices in Part B for those drugs where the Medicare program purchases the majority of the particular drug. Alternatively, Medicare could consider policies such as reference pricing or a Medicaid-style rebate system for Part B drugs.

Budget effects

According to an analysis by the HHS Office of Inspector General, about $2 billion in Federal savings would be achieved if manufacturers of the 20 costliest single-source drugs paid under Part B were required to pay the same rebates required under Medicaid (HHS OIG 2011b). Of these 20 drugs, 13 would meet the criterion that Medicare purchases the majority of a drug, representing rebate savings of $1.6 billion in 2010 (GAO 2012). Savings would be greater if based on the full list of qualifying drugs.

Discussion

Supporters of this option say that allowing negotiation or establishing a system of rebates in Part B means the Federal government would no longer have to accept any price set by a pharmaceutical company. Critics respond that forcing lower prices would reduce incentives for innovative research by pharmaceutical manufacturers.

OPTION 2.22

Lower the reimbursement for Part B drugs for which the price based on the average manufacturer price (AMP) is lower than the current ASP-based price

Since 2005, Medicare has paid for most Part B-covered drugs based on the ASP. Manufacturers generally must provide CMS with the ASP and volume of sales for all drugs on a quarterly basis; they also must report the average manufacturer price (AMP). By law, the HHS Inspector General identifies Medicare Part B prescription drugs with an ASP that exceeds the AMP by a certain threshold (currently set at 5 percent) and reports the financial impact of lower reimbursement amounts in these cases. CMS has the authority to substitute a price based on the AMP (103 percent of AMP) for the ASP-based price (106 percent of ASP) when it is lower, but has never used this authority. In the 2012 Physician Fee Schedule final rule, CMS added a requirement that AMP could only be substituted for ASP if the ASP exceeded the AMP by at least 5 percent in two consecutive quarters or three of the four previous quarters. Citing drug shortage concerns based on the lower prices, CMS has not implemented this requirement. The 2013 final rule would prevent use of the AMP-based price for drugs deemed to be in short supply. Under this option, CMS could finalize and implement a policy for lowering the reimbursement for drugs for which the AMP-based price is lower than the ASP-based price, including adding safeguards through rulemaking authority.

Budget effects

In 2012, the HHS Office of Inspector General estimated annual savings of as much as $17 million if the AMP-based price were substituted for 14 of the 29 drugs exceeding the 5 percent threshold (HHS OIG 2012a).

Discussion

Advocates suggest that this option fulfills the original intent of the law that CMS is supposed to lower reimbursement for drugs when the AMP-based price is lower. Because there are issues with both methodologies, use of both price standards was intended to make sure that Medicare does not overpay for Part B drugs. The HHS Inspector General has recommended implementation of this policy. Opponents of this option contend that, even with the protections proposed by CMS, the lower prices could exacerbate the problem of prescription drug shortages. Through rulemaking, CMS has tried to address this issue by considering whether drugs subject to this policy appear on a drug shortage list maintained by the FDA.

Drug Approval and Patent Policy

OPTION 2.23

Shorten the exclusivity period for biologics from 12 years to 7 years

Biologics—drugs made from living organisms and their products—are likely to be a large element of drug costs moving into the future. Although biologics represent a fairly small share of Medicare Part D costs today (about 13%5), they represent a large share of Part B drug costs. Biologics paid for under either Part B or Part D constitute about one-fourth of Medicare drug spending.6 As more self-administered biologics enter the market, their share of costs in Part D will increase. By one estimate, the list of most prescribed drugs (measured by costs) is switching from domination by traditional drugs for chronic conditions to biologics, a result of both patent term expirations for traditional brand drugs as well as increased use of biologics. The patents for biologics with about $20 billion in annual sales will expire between 2012 and 2018, creating a significant opportunity for savings if follow-on biologics can be approved and gain acceptance in the marketplace (Grabowski et al. 2011).

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act, enacted as part of the ACA, allows the FDA to approve follow-on biologics or biosimilars, by creating a pathway for more expeditious entry into the market (similar to treatment of generic drugs) and creating competition and lower prices. It also allows the FDA to create a formal designation of interchangeability for biosimilars, a status that will make it easier for physicians, patients, and payers to substitute the newly approved biosimilars as safe and effective alternatives. The FDA is in the initial stages of implementing the new statutory provisions. An estimate conducted in 2007 found that follow-on biologics might be priced at a discount of anywhere from 5 percent to 30 percent below current prices (Ahlstrom et al. 2007). Additional issues in the marketplace will be whether automatic substitution of biosimilars for the original biologic by pharmacists would be allowed (generally a matter of state law) and whether payers (including Medicare) will use formularies, cost sharing, and other incentives to encourage use of biosimilars.

One option to achieve Medicare savings would be to reduce the exclusivity period for biologics from 12 years to 7 years.

Budget effects

A proposal in the President’s budget for Fiscal Year 2013 to shorten the exclusivity period from 12 years to 7 years was estimated by CBO as saving the Federal government about $3 billion over 10 years (2013–2022).

Discussion

The specific proposal for shortening the exclusivity period from 12 years to 7 years is one means of getting follow-on biologics to the market more quickly. Proponents note that 7 years exceeds the 5-year exclusivity available to non-biologics, and that it still allows adequate time for manufacturers to recoup their research and development costs. But issues of acceptance and substitutability will be keys to shifting utilization and realizing these types of savings. It remains unclear whether State laws will permit automatic substitution of follow-on biologics at the pharmacy. In addition, many decisions to use these drugs, if administered by physicians, are not made at a retail pharmacy counter. Even if the FDA creates standards for the substitutability of these drugs, market adoption will require time to ensure acceptance by both physicians and patients. Also, there is concern that the considerably higher research costs for these drugs require more time to recoup costs and that shortening the exclusivity period could reduce incentives to develop new products (AARP Public Policy Institute 2012a; Frank 2012).

OPTION 2.24

Prohibit pay-for-delay agreements associated with patent exclusivity periods

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 created a new and faster pathway for approval of generic drugs by the FDA by proving that the generic drug is bioequivalent to the brand version. In general, the generic manufacturer may begin marketing its drug once all the original patents have expired. The law also provided a guaranteed minimum patent term for the original brand manufacturer and gave the first manufacturer with an approved generic version a period of 180 days when it would be the only generic on the market.

Some brand manufacturers have worked around the law by compensating a generic manufacturer for keeping its product off the market for a period of time—a practice referred to as pay-for-delay. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) found that they keep generic drugs off the market for an average of 17 months. Several cases, seeking to bar pay-for-delay agreements, are currently making their way through the Federal court system. In December 2012, the Supreme Court agreed to hear one of these cases and could resolve this issue in 2013.

The President’s Fiscal Year 2013 Budget called for prohibiting routine settlements of drug patent litigation. In doing so, it would remove current incentives for generic drug companies to challenge patents by prohibiting a generic drug company from accepting anything of value from the patent holder in a settlement other than an “early entry date” for the marketing of a generic drug. A similar proposal to ban pay-for-delay agreements (S. 27) was introduced in 2011 by Senators Charles Grassley (R-IA) and Herb Kohl (D-WI).

Budget effects

CBO scored the Grassley-Kohl legislation as saving the Federal government $4.8 billion over 10 years (2012–2021), including both spending and revenue effects (the total effect on public and private drug spending was estimated as $11 billion over the 10 years) (CBO 2011). A similar proposal included in the President’s Fiscal Year 2013 budget was estimated by CBO as saving about $5 billion over 10 years (2013–2022).

Discussion

Proponents of prohibiting pay-for-delay agreements argue that these agreements keep less expensive generic drugs off the market, thus preserving higher prices for brand manufacturers. Higher prices raise costs for Medicare and other payers, and lead to higher cost sharing for brand drugs for enrollees, which may have a negative effect on patients’ access and adherence to these drugs. Opponents contend that the settlements may save money if they resolve expensive litigation between generic and brand manufacturers that would take longer to be decided in court than the length of the agreed-on delay. According to both generic and brand manufacturers, banning patent settlements would delay competition and cut the number of new generics that enter the market prior to the expiration of brand patents. Some opponents also argue that generic manufacturers may be less likely to initiate legal action in an all-or-nothing environment where a financial settlement is excluded as an intermediate option (Federal Trade Commission 2011; Kesselheim et al. 2011; AARP Public Policy Institute 2012b).

References

Click to expand/collapse

AARP Public Policy Institute. 2012a. Allow Faster Market Access to Generic Versions of Biologic Drugs, June 2012.

AARP Public Policy Institute. 2012b. Prohibit Pay-for-Delay Agreements, June 2012.