Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost Sharing Policies as of January 2017: Findings from a 50-State Survey

Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment and Renewal Processes

The ACA standardized many streamlined enrollment and renewal procedures that states pioneered for children in the decades following the passage of CHIP in 1997. It also provided federal funding to support state upgrades to Medicaid eligibility systems, since many states had outdated systems that impeded updates to enrollment and renewal processes. Since the ACA was enacted, states have invested significant time and resources to upgrade or build new eligibility systems, using available federal funding. The modernized technology of these new systems has served as the cornerstone for states to implement the streamlined enrollment and renewal processes in the ACA. Under these processes, states are to use available electronic data to verify eligibility criteria at application and renewal; to provide individuals multiple methods to apply, including online, by phone, via mail, or in-person; to coordinate eligibility decisions with Marketplaces; and to renew Medicaid coverage every 12 months. Implementation of these processes has varied across states, in part reflecting different starting places before the ACA. However, as of January 2017, nearly all states have moved closer to the processes outlined in the ACA, with continued work occurring during 2016.

As a result of these efforts, the Medicaid enrollment and renewal experience has moved from a paper-based, manual process that could take days and weeks in some states to a modernized, technology-driven approach that can happen in real-time in a growing number of states. This shift has reduced burdens on individuals and states and led to shifting roles for eligibility workers, with some states scaling back or redirecting staff resources.

The findings below present the status of state systems and processes as of January 2017, and identify changes made to systems and processes during 2016. Unless otherwise indicated, the findings are for Medicaid systems and processes for children, pregnant women, parents and expansion adults. Many of the system upgrades and streamlined processes focused on these groups, and some separate eligibility rules and processes apply to seniors and individuals with disabilities. However, as indicated in the findings below, an increasing number of states are capitalizing on the federal funding available for system upgrades to expand improved systems to include all Medicaid groups and non-health programs.

Eligibility Systems

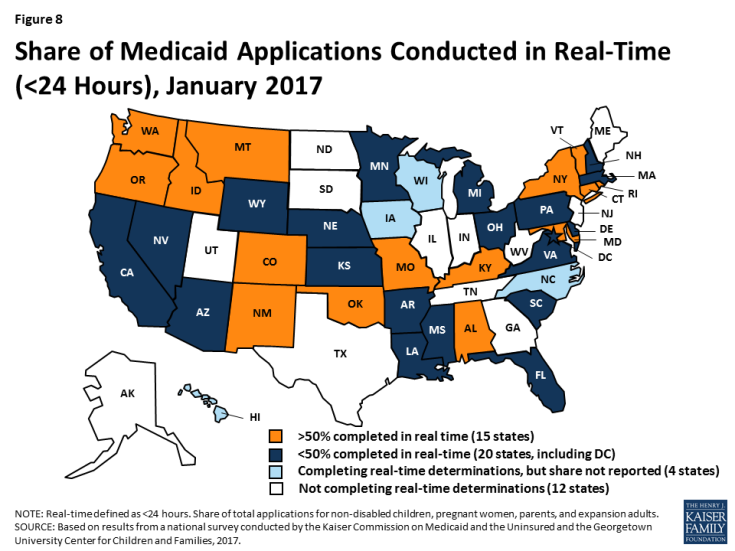

As of January 2017, 39 states can make Medicaid eligibility determinations in real-time (defined as within 24 hours). One of the notable features of upgraded eligibility systems is the ability to check against other electronic data sources in real-time or overnight to provide timely eligibility decisions. During 2016, Idaho and New Mexico began determining eligibility in real-time, and several more states anticipate reaching this milestone in early 2017. At least 50% of applications receive a real-time determination in 15 of the 35 states that were able to report this data (Figure 8), including 9 states that report over 75% of applications receive a real-time decision.

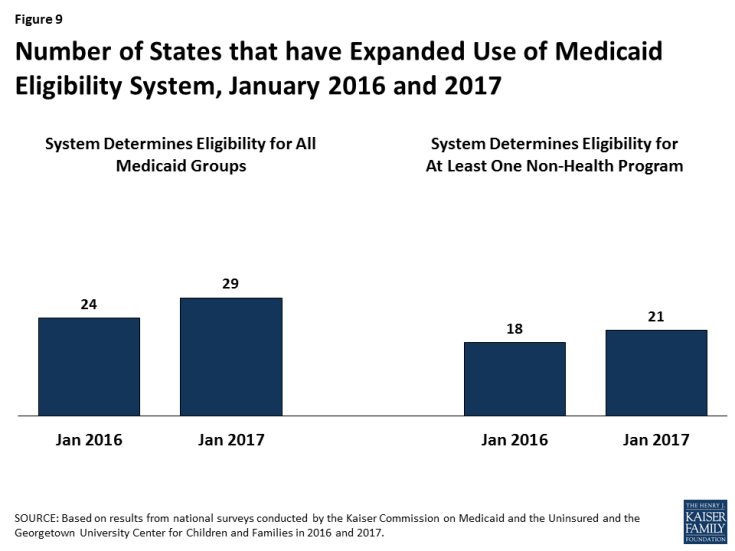

States are expanding improved Medicaid eligibility systems to include eligibility decisions for seniors and individuals with disabilities as well as non-health programs. Prior to the ACA, most states used one system to determine eligibility for all Medicaid groups as well as some non-health programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). Given the complexity of system upgrades, many states initially built their new systems to determine eligibility for the non-disabled groups affected by the ACA streamlining changes. As new systems were launched for these groups, states continued to use their old systems to determine eligibility for seniors and individuals with disabilities as well as non-health programs. As states finished initial implementation of new systems, a number began expanding them to include other groups and programs, using the ongoing federal funding available for system upgrades. During 2016, the number of states with systems that determine eligibility for all Medicaid groups grew from 24 to 29 (Figure 9). The number of states that include at least one non-health program in their Medicaid system increased from 18 to 21. In addition, several states added additional non-health programs to their systems during 2016. Thirty states plan to expand their systems to include seniors and individuals with disabilities and/or additional non-health programs in 2017 and beyond.

Figure 9: Number of States that have Expanded Use of Medicaid Eligibility System, January 2016 and 2017

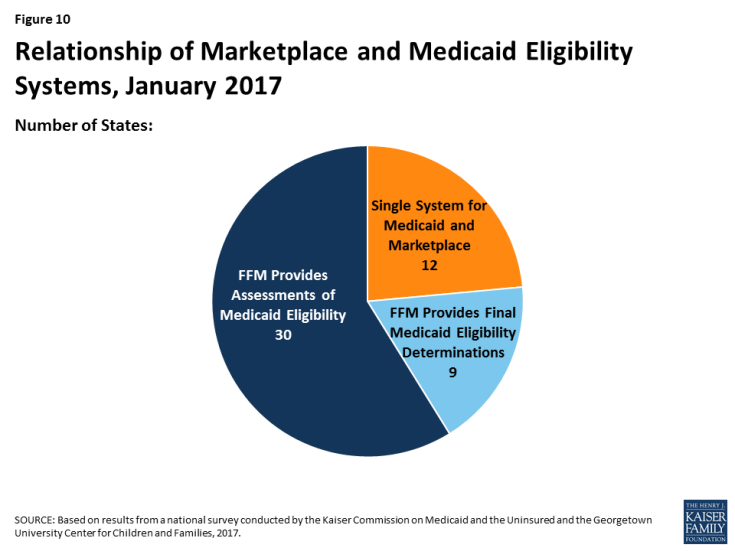

Medicaid eligibility systems are integrated with or connected to Marketplace systems in all states. In 12 of the states with a State-based Marketplace (SBM), there is one system that determines eligibility for both Medicaid and Marketplace coverage (Figure 10). The remaining 39 states coordinate with the Federally-Facilitated Marketplace (FFM), HealthCare.gov. This count reflects the dismantling of Kentucky’s SBM enrollment system, kynect, during 2016. States coordinating with the FFM must electronically transfer data back and forth with the FFM to coordinate Medicaid and Marketplace eligibility decisions. Nine of these states have authorized the FFM to make final Medicaid eligibility determinations based on the eligibility rules established by the state, enabling the states to enroll individuals in Medicaid after receiving the account transfer. During 2016, Louisiana began on relying final determinations to facilitate enrollment under its newly implemented Medicaid expansion. In the remaining 30 states, the FFM assesses Medicaid eligibility based on the state eligibility rules. In these states, after receiving the account transfer from the FFM, the Medicaid agency may check state data sources or request additional documentation before completing the eligibility determination. When the ACA was first implemented, there were significant problems with account transfers that contributed to delays in Medicaid enrollment. As of January 2017, only 6 states report ongoing, regular delays or difficulties with transfers, down from 20 as of January 2016.

Applications, Online Accounts, and Mobile Access

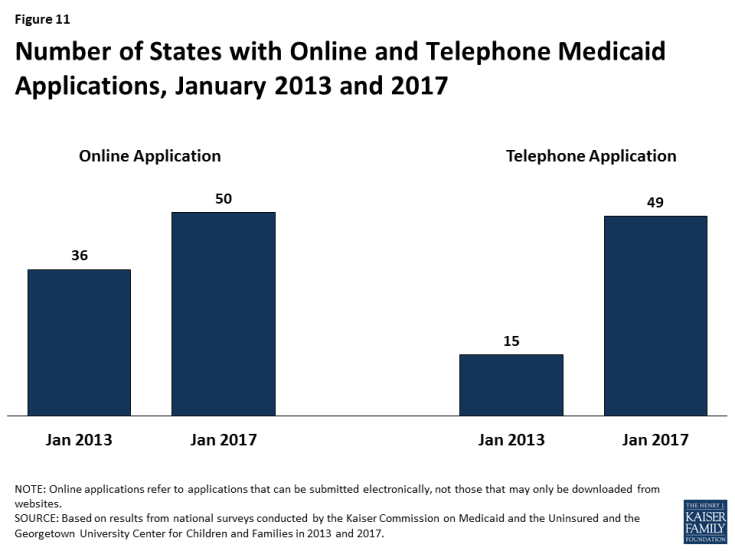

Individuals can apply for Medicaid online and by phone in nearly all states as of January 2017. Under the ACA, states must provide multiple methods for individuals to apply for health coverage, including online, by phone, by mail, and in person. In 2013, prior to ACA implementation, 36 states had an online Medicaid application and individuals could apply for Medicaid by phone in 15 states. As of January 2017, individuals can apply online for Medicaid in all states except Tennessee, and individuals can apply by phone in all states except Tennessee and Minnesota (Figure 11). At least 50% of Medicaid applications are submitted online in 18 of the 45 states that were able to report the share of applications received online.

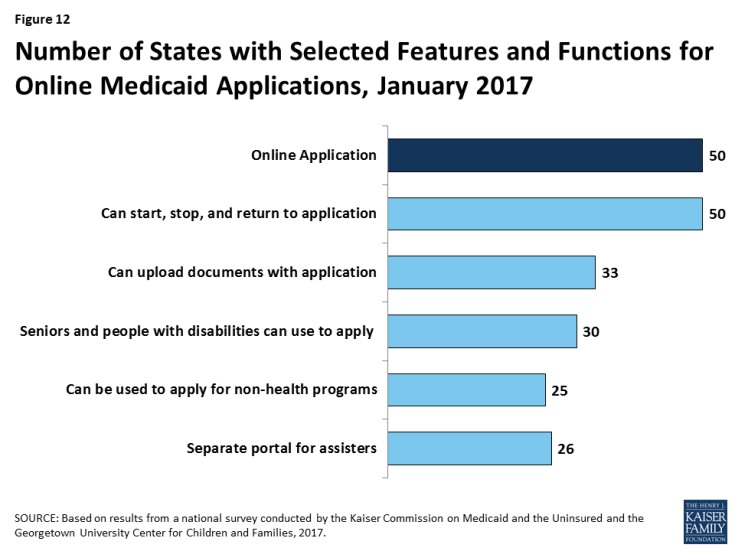

The features and functions of online applications vary across states (Figure 12). In all 50 states with an online application, applicants can start, stop, and return to finish the application at a later time. Applicants can upload electronic copies of documents with their application, if needed, in 33 states. With the addition of Ohio in 2016, all Medicaid groups, including seniors and people with disabilities, can apply through the online application in 30 states. Individuals can also apply for a non-health program, such as SNAP or TANF, using the online application in half of states. This count includes Kentucky, which launched an online multi-benefit application in 2016.

Figure 12: Number of States with Selected Features and Functions for Online Medicaid Applications, January 2017

Just over half of the states (26 states) have a web portal or secure login that enables consumer assisters to submit applications on behalf of consumers they help. Massachusetts and New Jersey added a portal for consumer assisters in 2016. In some states, the assister portals have additional functions or features that support the work of assisters, such as the ability to check a renewal date. These types of tools may help reduce workloads on state administrative staff, for example, if assisters are able to update addresses and other information. This functionality may also allow the state to track, monitor and report the work of assisters.

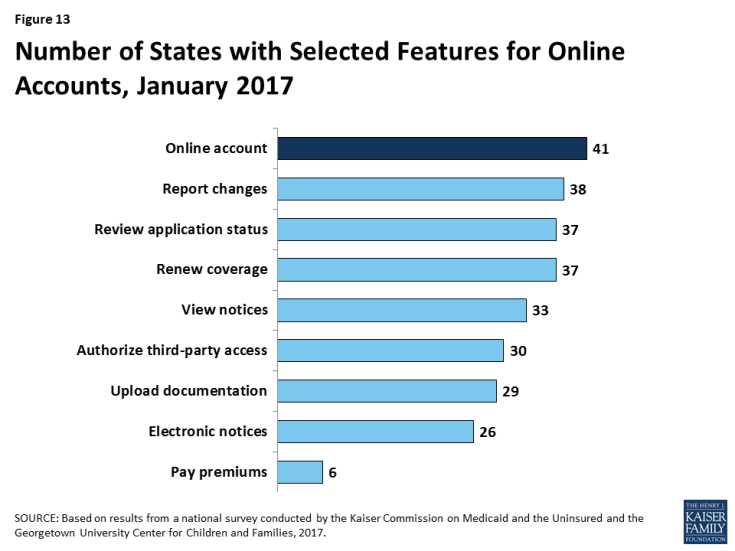

In 41 states, individuals can create an online account to manage their Medicaid coverage after enrollment (Figure 13). Most states provide a wide array of functions through online accounts and states have expanded functionality over time, with several states adding functions to their accounts in 2016. Most of these accounts allow enrollees to report changes, review the status of their application, to renew coverage, and to view notices. Smaller numbers allow enrollees to go paperless and receive electronic notices or to pay premiums. Online accounts create administrative efficiencies by reducing mailing costs, call volume, and manual processing of updates such as an address change. They also provide enrollees increased autonomy to manage and monitor their coverage.

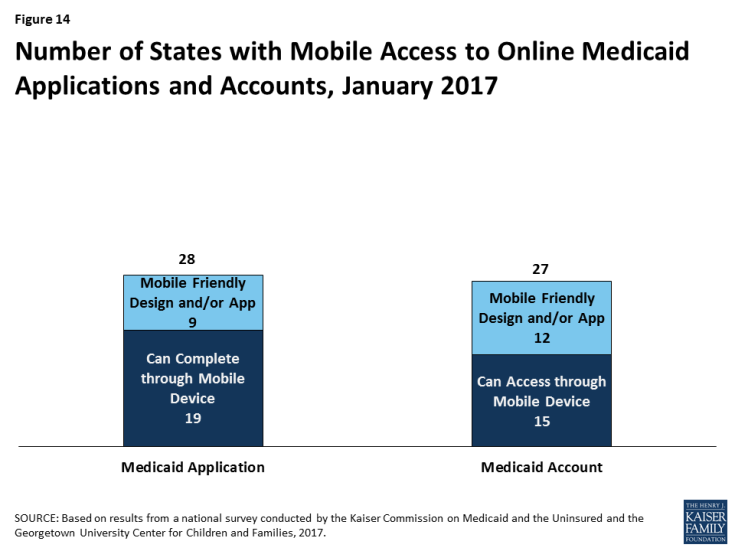

States have begun to make online applications and accounts accessible through mobile devices, such as phones or tablets. As of January 2017, individuals in 28 states can complete and submit the online Medicaid application through a mobile device. Nine of these states have designed a mobile-friendly version of the application and/or developed a mobile “app” for individuals to apply through a mobile device (Figure 14). Similarly, in 27 states, enrollees can access the online Medicaid account through a mobile device. In 12 of these states, there is a mobile-friendly version of the account and/or the state has created an “app” for enrollees to access the account through a mobile device. A number of states indicate that they plan to enhance mobile access to online applications and accounts in 2017 or beyond.

Figure 14: Number of States with Mobile Access to Online Medicaid Applications and Accounts, January 2017

Verification of Eligibility Criteria

One major shift under the ACA has been for states to rely on data from reliable electronic data sources rather than paper documentation to verify eligibility for Medicaid and CHIP. This change provides for a faster, more efficient eligibility determination process that reduces paperwork requirements for individuals and eases administrative burden on states, although it required significant upfront work by states to establish system connections to other data sources.

All states verify income eligibility, as well as citizenship and qualified immigration status of applicants, as required in Medicaid and CHIP. States must verify citizenship or qualified immigration status in advance of enrollment. Individuals who attest to a qualified status but who cannot have their eligibility confirmed electronically must be given a reasonable amount of time to provide adequate documentation. Nearly all states (44 states) verify income prior to enrollment, while 7 states complete the verification after enrollment. Verification of other eligibility criteria, such as age/date of birth, state residency, and household size vary across states and criteria, reflecting state options to verify this information before or after enrollment or to rely on self-attestation of information. If a state relies on self-attestation, it must verify information if it has any data on file that conflicts with the self-attestation.

All states access income and other information from the Social Security Administration, and many states also use state wage and unemployment data to verify eligibility criteria. As of January 2017, more than two-thirds of states get income and other information through the federal data hub, which was established by the ACA. The data hub enables states to access information from multiple federal agencies, including the Internal Revenue Service, the Social Security Administration (SSA), the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and a commercial database that provides earnings reported by large employers. States not using the federal hub rely on direct links to SSA and DHS databases that existed before the ACA. In addition, most states utilize state wage and unemployment data for income and other information. Fewer states rely on federal or state tax data.

Renewal Processes

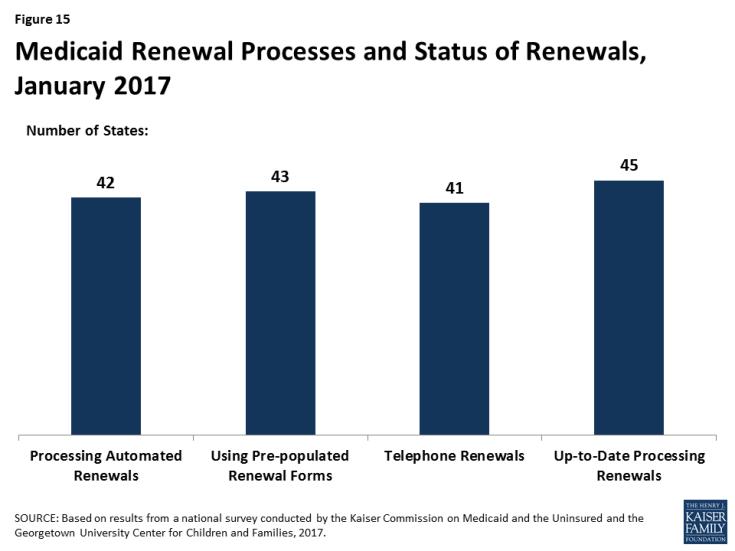

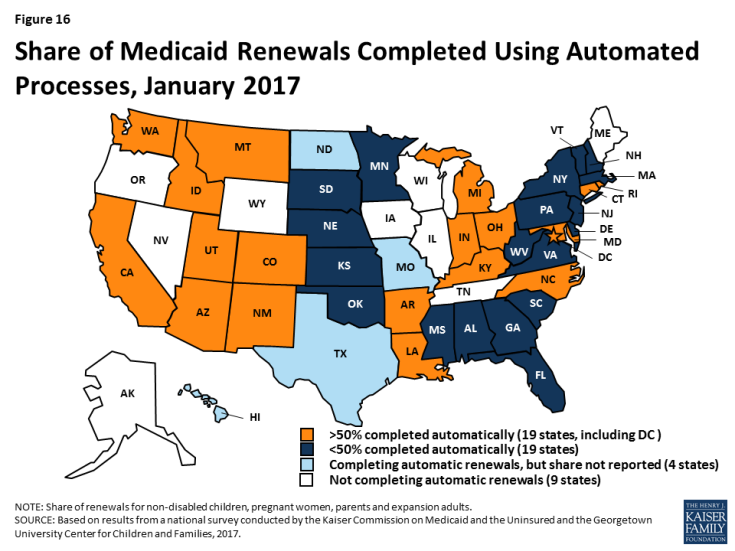

As of January 2017, 42 states were processing automated Medicaid renewals (Figure 15). This count includes five states that newly implemented automated renewal processes during 2016. Similar to data-driven enrollment, under the ACA, states are to use electronic data when available to renew coverage without requiring an individual to fill out a renewal form or provide documentation. This approach minimizes paperwork for individuals and reduces workloads for states. Among the 38 states able to report the share of renewals that are completed through automatic processes, 19 states report that more than 50% of renewals are automated (Figure 16), including 10 states with automatic renewal rates above 75%. In comparison, only 3 states reported that over 75% of renewals were automated as of January 2016.

If a renewal cannot be completed based on available data, states are expected to send a pre-populated notice or renewal form to the enrollee and to allow individuals to renew by phone. Between January 2016 and 2017, the number of states able to send pre-populated renewal forms or notices increased from 41 to 43. In 13 states, the forms are populated using updated sources of data from electronic data matches. With the addition of Arkansas and Texas during 2016, individuals can renew Medicaid coverage by phone in 41 states as of January 2017.

Most states are up-to-date on renewals as of January 2017. Six states report ongoing delays in processing renewals, most often citing system challenges or staff capacity as contributing factors.

Facilitated Enrollment and Renewal Options

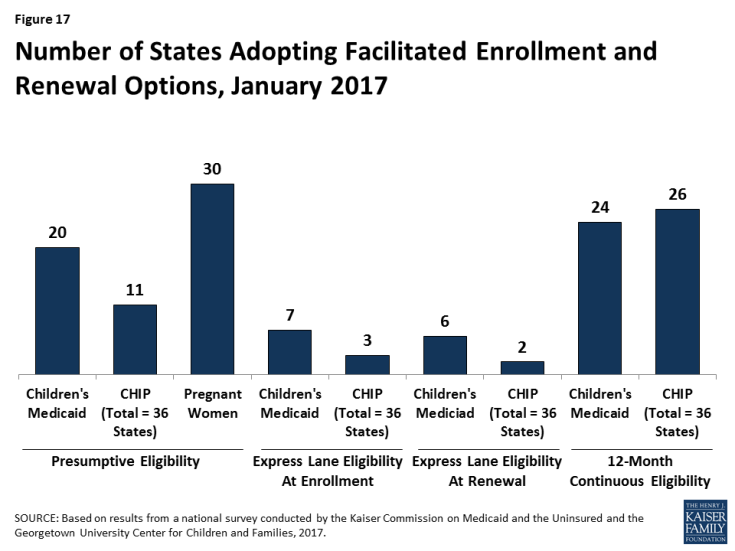

States can take up additional options to streamline enrollment and renewal beyond the processes standardized by the ACA. Most of these options have been available for many years prior to the ACA, but some were made newly available by the ACA. States’ use of these options may decline over time as states are able to achieve more real-time determinations and automated renewals through their standard processes. However, the options may remain useful for providing access to coverage for individuals who cannot have their eligibility verified in real-time. As of January 2017, states use a range of these options (Figure 17):

- Presumptive eligibility. Presumptive eligibility is a longstanding option in Medicaid and CHIP, which allows states to authorize qualified entities—such as community health centers or schools—to make a temporary eligibility determination to expedite access to care for children and pregnant women while the full application is processed. The ACA broadened the use of presumptive eligibility in two ways. First, it allows states that provide presumptive eligibility for children or pregnant women to extend the policy to parents, adults, and other groups. In 2016, two states (Missouri and Wyoming) expanded their use of presumptive eligibility. As of January 2017, over half of states use presumptive eligibility for children or pregnant women, while smaller numbers have adopted this policy for other groups. Second, the ACA gives hospitals nationwide the authority to determine eligibility presumptively for all non-disabled individuals under age 65. With the addition of Tennessee during 2016, hospital-based presumptive eligibility has been implemented in 46 states of as January 2017; 38 states report that hospitals are submitting applications through this process.

- Express Lane Eligibility. Express Lane Eligibility (ELE) is another longstanding option that allows states to enroll or renew children in Medicaid or CHIP based on findings from other programs, like SNAP. As of January 2017, seven states (Alabama, Colorado, Iowa, Louisiana, New York, South Carolina, and South Dakota) enroll children in Medicaid through ELE, while three states (Colorado, Iowa, and Pennsylvania) do so in CHIP. Georgia ended its use of ELE for children in 2016. New York has a waiver to use ELE to enroll parents. Six states use ELE to renew children’s Medicaid coverage (Alabama, Louisiana, Massachusetts, New York, South Carolina, and South Dakota), while two states (Massachusetts and Pennsylvania) do so in CHIP. Massachusetts also uses ELE to renew parents and expansion adults in Medicaid under Section 1115 waiver authority.

- 12-month continuous eligibility. States are expected to re-determine eligibility every 12 months. During this 12-month period, enrollees are required to report changes and will lose coverage if these changes make them ineligible. However, states have an option to provide 12-month continuous eligibility to children, which enables them to provide more stable coverage by disregarding changes in income until renewal. Continuous eligibility promotes retention and reduces the number of people moving on and off of coverage due to small changes in income, which decreases administrative costs. It also improves states’ ability to monitor quality of care given that many quality measures require at least 12 months of continuous enrollment. States can adopt 12-month continuous eligibility for children as an option, but must obtain Section 1115 waiver approval to provide it to parents and other adults. The number of states that have adopted 12-month continuous eligibility remained stable in 2016. As of January 2017, 24 states provide continuous eligibility to children in Medicaid, 26 of the 36 states with separate CHIP programs use it in CHIP, and Montana and New York provide it to parents and other adults under waiver authority.